New research has uncovered an Israeli military operation commanded by Moshe Dayan, whose goal was to forcibly remove Bedouin Palestinians from their lands. ‘Transferring the Bedouin to new territories would annul their rights as landowners and make them tenants on government lands,’ wrote Dayan in 1951. The documents show an orderly state expulsion plan…

Israel has evicted the Bedouin from the Negev village of Al-Arakib dozens of times, but they keep coming back. Israeli forces then demolish their homes again

To a large extent, Al-Arakib’s story is that of the entire Negev Bedouin community. Israel doesn’t recognize as theirs the tens of thousands of dunams they once lived on and where they still live…

By Netael Bandel, reposted from Ha’aretz (video below translated and added by IAK)

It’s quiet in the unrecognized Negev Bedouin village of Al-Arakib. It was even quiet a month ago, when stormy protests against the Jewish National Fund’s tree planting were taking place some 30 kilometers away.

But another issue could prove even more explosive, perhaps much more. And it stems from this quiet village.

At first glance, there’s nothing special about what Justice Ministry officials are calling the “national strategy case.” It’s just another Bedouin lawsuit over ownership of Negev lands that the state expropriated after the 1948 War of Independence.

Bedouin have testified previously that soldiers forcibly expelled them. For the first time, however, Algazi’s research seems to provide evidence of an orderly state expulsion plan

It will most likely fail in court, just like all its predecessors. And the Justice Ministry thinks it will be the last of its kind – that the state’s victory in this case would preclude any further Bedouin suits.

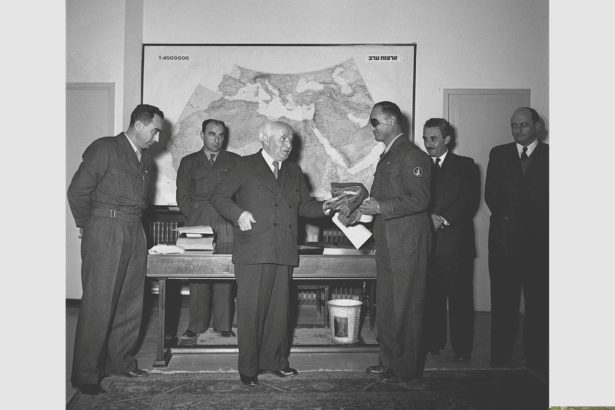

However, an appendix to this suit might change the outcome, albeit unlikely. It’s an opinion by Prof. Gadi Algazi, a historian from Tel Aviv University. His in-depth research has uncovered a military operation commanded by Moshe Dayan whose goal, the documents show, was to forcibly expel Bedouin from their lands.

“Transferring the Bedouin to new areas will revoke their rights as landowners and the land will be leased as government land,” wrote Dayan, then head of the army’s Southern Command, in a letter Algazi discovered. And a document written by the military government predicted that if the Bedouin, who refused to leave, didn’t move voluntarily, the army “would have to move them,” Algazi’s opinion added.

The Justice Ministry still thinks this case will end like all the others. Nevertheless, there’s a chance this historical material could set a legal precedent with implications far beyond recognizing Bedouin ownership of this one village.

What’s left of Al-Arakib is easy to reach. Head south on Route 40, turn right after the Lehavim Junction and you’ll see what looks like ruins. An ancient cemetery may be the clearest evidence of the life still here. At the moment, there’s a tent and two vans here. One van serves more as shelter from the weather than as a means of transportation.

The state has already evicted the Bedouin from Al-Arakib’s roughly 2,000 dunams dozens of times, but they keep coming back and reassemble. Israel then demolishes their homes again.

To a large extent, Al-Arakib’s story is that of the entire Negev Bedouin community. The state doesn’t recognize as theirs the tens of thousands of dunams they once lived on and where they still live.

‘The research proves that what David Ben-Gurion explicitly denied in the Knesset actually happened, and how. There was an organized transfer of Bedouin citizens’

Officially, the Bedouin left during the war and didn’t return, so the state expropriated the land. Then, the Land Acquisition Law of 1953 made this situation permanent. The law states that expropriated land would become state property if its Arab owners, despite still living in Israel, didn’t return to it between May 15, 1948 and April 1, 1952, and if the land was expropriated for “essential development needs” and still served those needs.

The state expropriated 247,000 dunams in the Negev, but 66,000 of them remain unutilized to this day. That underutilization has sparked a wave of Bedouin lawsuits, but the courts have rejected them time after time.

“Given the unique nature of the Acquisition Law and the unique historical circumstances leading to its enactment, there’s no room today for challenging the constitutionality of the expropriations carried out under it,” the Supreme Court wrote in three separate rulings. In one, then-Justice Asher Grunis wrote that even though the courts have authority to hear all these cases, “the decision, practically speaking, is largely moot.”

Nevertheless, “largely” isn’t the same as “always,” especially since the Bedouin are now raising a new argument – that the expropriation itself was illegal. Granted, Bedouin have testified previously that soldiers forcibly expelled them. For the first time, however, Algazi’s research seems to provide evidence of an orderly state expulsion plan.

‘Move away for a little while’

Ismail Mohammed Salem Abu Madiam was born in Al-Arakib in 1939, a scion of a family that had lived there for many years. They grew various crops, including wheat, barley and corn. They also raised camels, horses, donkeys and sheep. When he was a child, during the British Mandate, he would go to Be’er Sheva with his uncle to sell the sheep.

“I was 9 when the war broke out in 1948,” he said in an affidavit to the court. “We feared attacks by the army, so the neighbors’ families moved to our plot to be less vulnerable. They returned to their lands when the end ended.”

When he was 14, he said, the military governor came to the village to speak with his grandfather. “He ordered us to move away for a little while. We were told the army was planning maneuvers in the area and we could come back afterward.”

‘I scrolled down the screen in the archive and the file got stuck on page 999. It was probably just a simple technical error – somebody didn’t think there’d be files any longer than that’

They were moved to a site around 300 meters from their land. They eventually returned to Al-Arakib and he bought a house in Rahat, not far from his family’s lands.

“Throughout this period, I never knew the state claimed that the land wasn’t ours or that it had been expropriated,” he said. But when the repeated evictions began, he and other villagers realized that the state viewed the land as no longer theirs.

Over the past decade, Al-Arakib has become the standard bearer for the Bedouin’ fight for recognized ownership of Negev lands. The state has evicted the residents – who consider themselves the owners but are called squatters – dozens of times.

The narrow opening left by Grunis’ ruling encouraged the Abu Madiam and Abu Freih families now to sue for ownership of Al-Arakib’s 2,000 dunams. They are represented in the Be’er Sheva District Court by attorneys Michael Sfard and Carmel Pomerantz.

Another local tribe filed a similar petition and lost, but that petition lacked Algazi’s findings.

“Even if we don’t win, heaven forbid, I’ve achieved my goal,” said Dr. Awad Abu Freih, the head Sapir College’s biotechnology department and the lead plaintiff. “The history has been told, and also written. My story, that of my father and my grandfather, won. This isn’t just another case, just another name. This is Al-Arakib, which has insisted on continuing to live and refused to die, even if they buried us alive.”

Algazi’s research reveals for the first time the large-scale operation to evict the Bedouin and move them elsewhere in the Negev that Southern Command launched in November 1951, with approval from Chief of Staff Yigael Yadin. The eviction had security justifications, but it also had another goal – severing the Bedouin’s ties with their lands.

“The research proves that what David Ben-Gurion explicitly denied in the Knesset actually happened, and how,” Algazi told Haaretz, referring to Israel’s first prime minister. “There was an organized transfer of Bedouin citizens from the northwestern Negev eastward to barren areas, with the goal of taking over their lands. They carried out this operation using a mix of threats, violence, bribery and fraud.”

He said his opinion shows how the operation was carried out, down to the level of the notes exchanged by military government officers implementing it. The most senior of them knew it was an illegal operation, and that’s why it was important to them not to give the Bedouin written “transfer” orders, he added.

Another discovery was “the Bedouin resistance and protests, the stubbornness with which they tried to hold onto their land, even at the cost of hunger and thirst, not to mention the army’s threats and violence,” he said. Yet another finding was the way the official story was drafted. “It shows how they censored and edited the reports step by step, until the version in which the Bedouin moved ‘voluntarily’ was accepted,” Algazi said.

For years, Algazi has been an active participant in the Bedouin’s struggle in general and in that of Al-Arakib’s residents in particular. He began his current research in 2011 by delving into documents in the archives of the Defense Ministry and the Negev kibbutzim. “I had heard things and wanted to see if there was any truth to them,” he explained.

“I found a treasure trove in the kibbutzim’s archives. Sometimes I found myself with an archivist who had devoted years to collecting and organizing the material. Other times I was simply sent to dig through an old cupboard. But in any case, I never imaged this would gradually turn into research that would keep me busy for eight years.”

Algazi’s research led to the letter Dayan sent to the General Staff on September 25, 1951. “It’s now possible to transfer most of the Bedouin in the vicinity of [Kibbutz] Shoval to areas south of the Hebron-Be’er Sheva road,” he wrote. “Doing so will clear around 60,000 dunams in which we can farm and establish communities. After this transfer, there will be no Bedouin north of the Hebron-Be’er Sheva road.”

Dayan raised security considerations in favor of moving the Bedouin to the area of the Jordanian border, but security was not the only consideration. “Transferring the Bedouin to new territories will annul their rights as landowners and they will become tenants on government lands.” Dayan made a similar statement a year earlier, in June 1950, during a meeting of Mapai. “The party’s policy should be aimed at seeing this community of 170,000 Arabs as if their fate has yet to be sealed. I hope that in the coming years, we will be able to transfer these Arabs out of the Land of Israel.” A year after expressing this aspiration, the documents reveal, he partially executed his plan, moving them within but not outside the state’s borders.

Dayan’s letter was not easy to find, says Algazi. “In November 2017, a huge, disorganized file of correspondence of the military government, containing 1037 pages, was released for viewing,” he recalls. “The scanned file was once a big fat, disorderly folder lying on a dusty shelf somewhere full of correspondence, some interesting, some boring. I scrolled down the screen in the archive and the file got stuck on page 999. It was probably just a simple technical error – somebody didn’t think there’d be files any longer than that.”

Algazi was told the file would be fixed. Two years later, he was informed it was. “Dayan’s letter turned up in the final 40 pages along with another two parts of the correspondence that completed the missing puzzle pieces,” he recalls. “I was sitting in the archives, and I could hear Dayan speaking. In his unique style, he said openly things that others would wrap in cellophane paper: ‘Transferring the Bedouin to new territories would annul their rights as landowners and make them tenants on government lands.’ Clear and simple.”

But, adds Algazi, the cunning Dayan, in charge of Southern Command, thought he had managed to arrange the transfer with the Bedouin’s agreement and was making sure not to explain exactly how he achieved that agreement. “Dayan cooked it up, and it failed,” he says. “When it transpired that there was no agreement, the pressure and violence began. Indeed, right after Dayan’s letter, I found in the same file a report by the military government concerning the Bedouin’s refusal to move – and what needs to be done to meet the goal.” This time, the author is the acting military governor of the Negev, Major Moshe Bar-On. He wrote: “We received orders from the head of Southern Command to pressure the Bedouin tribes in the northern region, even going so far as to say that if they don’t move of their own free will, the army will be forced to move them.”

The means of ‘persuasion’

There were many means of persuasion, but some of the information remains censored. For example, Maj. Misha Hanegbi described in his report on November 21, 1951, a patrol in the region that was aimed at “hastening” the transfer of Bedouin when it ran into “stiff resistance from the locals to leaving their lands.” The report stated that only “after negotiations” was the transfer carried out. However, an entire paragraph is then blacked out – one that could shed light on the means used to “persuade.”

However, testimonies submitted by locals as court affidavits reveal some details. “I remember how the army ordered my family to leave Al-Arakib and head northward,” recalls 80-year-old Hussein Ibrahim Hussein. “Some people who resisted the deportation were arrested. We were told the lands were being confiscated for a few months for military purposes. The Military Police turned up, tied up our things, and told them to move.” They moved but tried to return. It didn’t end well. “I was arrested. My uncle was arrested, we were all arrested” he states. “We would go in to see, the army would detain us for a day or two and then release us.”

Not everyone in the military supported the operation. The Negev governor, Lt. Col. Michael Hanegbi, wrote to the chiefs of staff that “the presence of the Bedouin in the area serves as a buffer against attacks by infiltrators from the east against our settlements along that line. The fact is that our settlements in this area hardly suffer from attacks, which are very frequent in other areas.” He also warned that the alternative lands designated for the Bedouin were barren and that “the problem of water is the eastern region was getting worse.” On another occasion, Hanegbi reported that “despite restrictions prohibiting the use of violence, attempts were made, with the agreement of command, to try and force them to move.” He added: “A military government unit took down a number of tents and loaded them on to a vehicle. The tent owners did not leave and did not join their families who had been transferred.”

Additional testimonies to events were received from residents of nearby kibbutzim. The area “was surrounded by police and military government in military vehicles,” Yosef Tzur of Kibbutz Shuval wrote to kibbutz movement leaders. “People fled, tents were taken down and those who were caught were piled into vehicles and taken to Tel Arad.” A little of what happened when the uniformed officers turned up was revealed by Sheikh Suleiman Al-Okbi in an interview with Yedioth Aharonoth in 1975. “Military units began turning up on our lands from time to time and they would shoot in the air,” he told Yedioth. “People were scared and the women were frightened to work in the field and graze the animals.”

Lieutenant Colonel Hanegbi wrote in one of his letters that “the transfers were conducted primarily through persuasion and economic pressure.” He went on to reveal more. “We had no legal foundation and we were also under orders not to use force, so we had to behave cautiously in our actions and without becoming entangled in legal problems.”

Algazi found evidence of this economic pressure in a note written by the prime minister’s advisor on Arab affairs back then, Yehoshua Palmon (who, the researcher says, was “the most senior figure in setting policy toward Israel’s Arab citizens”). Palmon wrote that the military government prevented the Bedouin from sowing their lands to pressure them into agreeing to move. There was evidence of this practice on the ground. Kibbutz Shuval wrote to the Mapam Party on January 28, 1952, that “the military government forced the Bedouin to leave their lands. Their food supplies were stopped.” According to the kibbutz residents, food supplies were stopped over a period of months.

Other methods of harassing the Bedouin were employed according to an affidavit submitted to the courts by Hussein Ibrahim al-Touri, who was born in 1942. He described how the military “would come and harass us, take us to prison, and so on.” He stated: “The soldiers would take a rope, tie a tent to a command car and demolish it. We were told to move and that if we were to return they would burn our homes down and take us to Jordan.” Abed Hasin Abu-Sakut, a fellow villager, said that after leaving their lands, they returned occasionally, but then “the soldiers would shoot or arrest us and fine us.”

They didn’t just return to their lands of their own accords. Algazi says the state gave the Bedouin the impression they were only being temporarily evacuated. In a letter from the time, Captain Avraham Shemesh wrote that he had allowed evacuated Bedouin to return from time to time to work the soil “until the Beni Okba tribe was allowed to return to its lands.” According to the testimony of local Bedouin similar statements were repeatedly made to them. “The elders said the military governor gave my uncle a letter saying that the army needs the land for six months, after which we would return,” Ahmad Salam Mahmoud al-Okbi testified in court. “I remember how a year after the deportation in 1951, my uncle returned to the land with others. I was there and grazed sheep. One day, a military officer by the name of Sasson Bar Zvi who I knew turned up. He said that if we didn’t leave, he would take us to jail.”

The document reveals that the area kibbutzim raised objections on several occasions to the policy. In late 1951, Kibbutz Mishmar Hanegev, Kibbutz Shuval and Kibbutz Safiach (Beit Kama) wrote a letter to the Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee protesting the transfer of Bedouin, arguing that they helped settlement.

“We felt a duty to emphasize that this was being done through conspiracy, bribery, and pressure,” they wrote, reporting that “some tents were moved by force.” The kibbutzim’s protest led Mapan to investigate the matter in November 1952. Lieutenant Colonel Hanegbi testified that he had only carried out the orders given him, but confirmed that the army’s intention was to “undermine the status of the tribes being transferred, so they would leave the country.” As part of the operation, he said, “scare tactics and bribery were used, but not always.” Hanegbi contended that military personnel had behaved “cruelly and crudely” toward the Bedouin. As a result, a recommendation was made to annul his party membership.

Algazi says that while there have been a number of studies in recent year about the period of military rule, “there was no study or affirmation until today that the 1951 deportation took place.”

A matter of timing

Throughout the hearings, the state and the prosecution did not deny the operation’s existence but argued that against Algazi’s opinion emphasized the civilian considerations of the transfer while playing down the security considerations. The state also raised a claim concerning the operation’s timetable. They argued that operation began before the law was passed, so Dayan could not have known what criteria would be set for seizing land. However, some could argue that Dayan possibly knew about long-term political plans because of his position and standing.

Another issue concerns how long Al-Arakib has existed. The state denied the claim that there was a permanent settlement on Al-Arakib’s lands. The petitioners assert there had been a Bedouin settlement at the site prior to the state’s establishment, based on an opinion provided by Forensic Architecture, a research group at the University of London. Forensic Architecture, headed by Prof. Eyal Weizman, combined digital tools with maps and reconnaissance of Al-Arakib to reach that conclusion. The opinion will take on greater significance if the claimants manage to progress to the second stage of the hearing on proof of ownership.

The state argues the court should reject the claim due to a delay of decades in filing it. But the Bedouin also have a response for that: They were never told the lands were appropriated and the state misled them into thinking the lands had been taken away only temporarily. A letter received in 2000 from the Israel Lands Administration stated that “no appropriation has taken place” on the lands.

One way or the other, all parties are waiting to hear from the court. Meanwhile, Algazi expects to make further findings. “The difficulty is in reconstructing an operation carried out by people who knew it was not really legal, and therefore made sure not to put down certain things in writing,” he tells Haaretz. “In addition, although we are talking about events that took place 70 years ago, only some of the documents have been revealed. We are waiting for the day when we will be able to study all of them.”

Netael Bandel is an attorney who writes for Ha’aretz

RELATED READING:

- Cleansing the Negev: Israel plans to evict “tens of thousands” of Palestinian Bedouin

- Israeli harassment of Palestinian Bedouin village won’t let up

- A cruel, yet very usual Israeli incident that almost nobody knows about

- The plight and blight of home demolition in Israel and Palestine

- Israeli High Court: Palestinian homes “too close to the wall, must be demolished”

- Israel pursues possible war crime in village demolition

- In 15 years, Israel forced 3,000 Palestinians from their Jerusalem homes

VIDEOS:

- WATCH: Palestinian father forced to demolish home in Jerusalem

- Expansion in East Jerusalem: Jeff Halper & Alison Weir

- Daily Life in Occupied Palestine