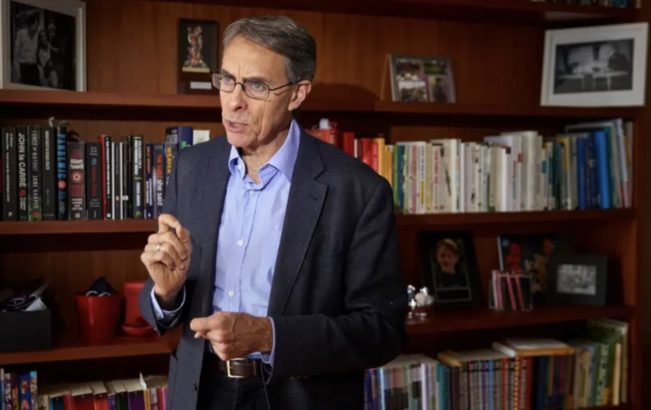

Kenneth Roth: “I was told that my fellowship at the Kennedy School was vetoed over my and Human Rights Watch’s criticism of Israel. How can an institution that purports to address foreign policy – that even hosts a human rights policy center – avoid criticism of Israel?”

by Kenneth Roth, reposted from the Guardian, January 10, 2023

During the three decades that I headed Human Rights Watch, I recognized that we would never attract donors who wanted to exempt their favorite country from the objective application of international human rights principles. That is the price of respecting principles.

Yet American universities have not articulated a similar rule, and it is unclear whether they follow one. That lack of clarity leaves the impression that major donors might use their contributions to block criticism of certain topics, in violation of academic freedom. Or even that university administrators might anticipate possible donor objections to a faculty member’s views before anyone has to say anything.

That seems to be what happened to me at Harvard’s Kennedy School. If any academic institution can afford to abide by principle, to refuse to compromise academic freedom under real or presumed donor pressure, it is Harvard, the world’s richest university. Yet the Kennedy School’s dean, Douglas Elmendorf, vetoed a human rights fellowship that had been offered to me because of my criticism of Israel. As best we can tell, donor reaction was his concern.

Soon after I announced my departure from Human Rights Watch, the Kennedy School’s Carr Center for Human Rights Policy reached out to me to discuss offering me a fellowship. I had long been informally involved with the Carr Center, which seemed like a natural place for me to spend a year as I wrote a book. So, I accepted in principle. The only missing step was the dean’s approval, which we all assumed would be a formality.

Indeed, in anticipation of my stay at the school, I reached out to the dean to introduce myself. We had a pleasant half-hour conversation. The only hint of a problem came at the end. He asked me whether I had any enemies.

It was an odd question. I explained that of course I had enemies. Many of them. That is a hazard of the trade as a human rights defender.

I explained that the Chinese and Russian governments had personally sanctioned me – a badge of honor, in my view. I mentioned that a range of governments, including Rwanda’s and Saudi Arabia’s, hate me. But I had a hunch what he was driving at, so I also noted that the Israeli government undoubtedly detests me, too.

That turned out to be the kiss of death. Two weeks later, the Carr Center called me up to say sheepishly that Elmendorf had vetoed my fellowship. He told Professor Kathryn Sikkink, a highly respected human rights scholar affiliated with the Kennedy School, that the reason was my, and Human Rights Watch’s, criticism of Israel.

That is a shocking revelation. How can an institution that purports to address foreign policy – that even hosts a human rights policy center – avoid criticism of Israel?

Elmendorf has not publicly defended his decision, so we can only surmise what happened. He is not known to have taken public positions on Israel’s human rights record, so it is hard to imagine that his personal views were the problem.

But as the Nation showed in its exposé about my case, several major donors to the Kennedy School are big supporters of Israel [see names below]. Did Elmendorf consult with these donors or assume that they would object to my appointment? We don’t know. But that is the only plausible explanation that I have heard for his decision. The Kennedy School spokesperson has not denied it.

Some defenders of the Israeli government have claimed that Elmendorf’s rejection of my fellowship was because Human Rights Watch, or I, devote too much attention to Israel. The accusation of “bias” is rich coming from people who themselves never criticize Israel and, typically using neutral sounding organizational names, attack anyone who criticizes Israel.

Moreover, Israel is one of 100 countries whose human rights record Human Rights Watch regularly addresses. Israel is a tiny percentage of its work. And within the Israeli-Palestinian context, Human Rights Watch addresses not only Israeli repression but also abuses by the Palestinian Authority, Hamas and Hezbollah.

In any event, it is doubtful that these critics would be satisfied if Human Rights Watch published slightly fewer reports on Israel, or if I issued less frequent tweets. They don’t want less criticism of Israel. They want no criticism of Israel.

The other argument that defenders of Israel have been advancing is that Human Rights Watch, and I, “demonize” Israel, or that we try to “evoke repulsion and disgust”. Usually this is a prelude to charging that we are “antisemitic”.

Human rights advocacy is premised on documenting and publicizing governmental misconduct to shame the government into stopping. That is what Human Rights Watch does to governments worldwide. To equate that with antisemitism is preposterous. And dangerous, because it cheapens the very serious problem of antisemitism by reducing it to criticism of Israel.

The issue at Harvard is far more than my own academic fellowship. I recognized that, as an established figure in the human rights movement, I am in a privileged position. Being denied this fellowship will not significantly impede my future. But I worry about younger academics who are less known. If I can be canceled because of my criticism of Israel, will they risk taking the issue on?

The ultimate question here is about donor-driven censorship. Why should any academic institution allow the perception that donor preferences, whether expressed or assumed, can restrict academic inquiry and publication? Regardless of what happened in my case, wealthy Harvard should take the lead here.

To clarify its commitment to academic freedom, Harvard should announce that it will accept no contributions from donors who try to use their financial influence to censor academic work, and that no administrator will be permitted to censor academics because of presumed donor concerns. That would transform this deeply disappointing episode into something positive.

Kenneth Roth served as executive director of Human Rights Watch from 1993 to 2022. He is currently writing a book.

Excerpts from The Nation:

According to people knowledgeable about the [Kennedy] school’s programs, its administration is terrified of touching anything related to Palestine, and Palestinian voices have largely been silenced. That’s due not to any particular administrator, they say, but to “the ethos of the place” and the people who fund the Belfer Center.

Prominent among those people is Robert Belfer, who has donated more than $20 million to the Kennedy School since the 1980s—money that has come from his family’s fortune. Born in 1935 and raised in Krakow, Poland, Belfer fled the Nazis with his family in early 1941 and arrived in New York in January 1942, speaking no English. He graduated from Columbia University and Harvard Law but decided to join his father’s business. Arthur Belfer worked in feathers and down, selling products to the US military, including down-filled sleeping bags, but in the 1950s he branched out into foam rubber and then oil, buying an oil-producing tract in north Texas. The company he created, Belco Petroleum, did so well that Arthur eventually made the Forbes 400. In 1983, he sold Belco to InterNorth. In 1985, InterNorth merged with Houston Natural Gas, which then changed its name to Enron. Robert joined Enron’s board, and the family became the company’s largest shareholder. In 1992, a year before his death, Arthur helped Robert set up a separate entity, Belco Oil & Gas, which went public in 1996, bringing in more than $100 million.

Through his donations to the Kennedy School, Belfer got to know Graham Allison. Allison helped build the Belfer Center, and Belfer in turn arranged for Allison to join the board of Belco. (In 1999, Allison bought 39,000 shares of Belco stock; in 2000, the company announced two stock buybacks, which nearly doubled its stock price. A request to Allison for comment went unanswered.)

After a dizzying rise that saw Enron’s stock hit $90 a share in the summer of 2000, the company imploded in 2001 amid revelations of fraudulent accounting and insider trading. By the time it declared bankruptcy in December 2001, its shares were trading for pennies, and the Belfers’ stake—almost $2 billion a year earlier—had virtually vanished. As a board member who stood by while the company collapsed, Robert Belfer faced the wrath of thousands of shareholders whose investments were wiped out. But the Belfers retained sizable holdings in real estate as well as control of Belco Oil, and in August 2001 that company merged with Westport Resources in a transaction valued at around $866 million.

So despite Enron’s collapse, Robert Belfer remained very rich—and philanthropic. In addition to the Kennedy School, he and his wife, Renée, have given to an array of cultural institutions, medical research centers, private schools, universities, and Jewish and Israeli institutions. In a 2006 interview with the US Holocaust Museum, Belfer observed that most of his extended family (including his paternal grandparents) perished in World War II—a loss that gave him “a sense of identity” of “being Jewish, of being very supportive of Israel.”

According to the 990 forms of his family foundation, between 2011 and 2015 Belfer gave more than $300,000 to the American Jewish Committee, on whose board of governors he sits. In 2018, he joined with the Anti-Defamation League to endow a new fellowship at the Belfer Center to study disinformation, hate speech, and toxic content online. Every year, the school hosts three ADL Belfer Fellows. In short, the primary funder of the Belfer Center has been a significant backer of two of the groups—the AJC and the ADL—that Peter Beinart cited as assailing human rights organizations because of their criticism of Israel.

Stephen Walt has been the Robert and Renée Belfer Professor of International Relations for the past two decades. In 2007, when Walt and John Mearsheimer published The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy—which argued that AIPAC and other pro-Israel groups have redirected US policy away from America’s national interests—it caused an uproar at the Kennedy School, including complaints from some Wexner fellows. After a summary version appeared in the London Review of Books, the school was flooded with calls from “pro-Israel donors,” according to the New York Sun—Robert Belfer reportedly among them. Then-Dean David Ellwood asked Walt to omit Belfer’s name from his professor’s title in any publicity related to the article. Walt declined.

Belfer’s influence at the Kennedy School extends far beyond his center. He and his son Laurence sit on the Dean’s Executive Board—“a small group of business and philanthropic leaders who serve as trusted advisors to the Dean and are among the most committed financial supporters of the School,” according to its site. The board’s chair, David Rubenstein, is the cofounder and former CEO of the Carlyle Group, the private equity giant, and one of the most well-connected members of the US financial and cultural elite; among the many prestigious boards on which he sits is the Harvard Corporation, the university’s main governing body.

The 16 members of the Dean’s Executive Board also include Idan Ofer and his wife, Batia. Idan is the son of Sammy Ofer, an Israeli shipping magnate who until his death in 2011 was one of Israel’s richest men. Worth about $10 billion, Idan has come under fire in Israel for moving to London to reduce his tax bill and for a lavish lifestyle highlighted by the €5 million party that he threw on the island of Mykonos for his 10th wedding anniversary.

The Kennedy School dean cannot afford to lose the confidence of this board; nor can he afford to alienate the US national security community, with which the school has such close ties. The Carr Center itself is enmeshed in the US foreign policy establishment: Samantha Power has served on the National Security Council and as US ambassador to the United Nations, and she currently heads the US Agency for International Development.

In 2018, the Kennedy School opened a renovated campus, made possible by a capital campaign that raised more than $700 million. Anchoring it were three buildings bearing the names Ofer, Rubenstein, and Wexner. “We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us,” Dean Elmendorf said at the ribbon-cutting ceremony, adding that “our buildings are the structural framework for our lives here. Here important ideas will be born and nurtured. Generations of students will learn from world-class scholars and practitioners.”

OTHER EXAMPLES OF CRITICS OF ISRAEL BEING PENALIZED:

- I Was Fired For Criticizing Israel. Now I Dig Holes For A Living

- Texas: she didn’t sign the “Israel Oath,” so she got fired

- How the Media Cracks Down on Critics of Israel

- Witch Hunt Is Raging Against Critics of Israel throughout Europe

MORE ON THE PRO-ISRAEL BIAS ON CAMPUS:

- When university donors have a pro-Israel agenda

- Pro-Israel students pressure Butler U to cancel an event featuring Angela Davis

- How Israel loyalists keep US officials in line: Ambassador nominee is taken down

- Repression of speech and scholarship on Palestine needs to end

- Maccabee Task Force covertly funded 3,200 pro-Israel events on US campuses

- The Pro-Israel Push to Purge US Campus Critics

- Electronic Intifada: Israeli soldiers harass students during SJP event on US campus

VIDEOS: