By Jesse Drucker, New York Times

It was the summer of 2012, and Jared Kushner was headed downtown.

His family’s real estate firm, the Kushner Companies, would spend about $190 million over the next few months on dozens of apartment buildings in tony Lower Manhattan neighborhoods including the East Village, the West Village and SoHo.

For much of the roughly $50 million in down payments, Mr. Kushner turned to an undisclosed overseas partner. Public records and shell companies shield the investor’s identity. But, it turns out, the money came from a member of Israel’s Steinmetz family, which built a fortune as one of the world’s leading diamond traders.

A Kushner Companies spokeswoman and several Steinmetz representatives say Raz Steinmetz, 53, was behind the deals. His uncle, and the family’s most prominent figure, is the billionaire Beny Steinmetz, who is under scrutiny by law enforcement authorities in four countries. In the United States, federal prosecutors are investigating whether representatives of his firm bribed government officials in Guinea to secure a multibillion dollar mining concession. In Israel, Mr. Steinmetz was detained in December and questioned in a bribery and money laundering investigation. In Switzerland and Guinea, prosecutors have conducted similar inquiries.

The Steinmetz partnership with Mr. Kushner underscores the mystery behind his family’s multibillion-dollar business and its potential for conflicts with his role as perhaps the second-most powerful man in the White House, behind only his father-in-law, President Trump.

Although Mr. Kushner resigned in January from his chief executive role at Kushner Companies, he remains the beneficiary of trusts that own the sprawling real estate business. The firm has taken part in roughly $7 billion in acquisitions over the last decade, many of them backed by foreign partners whose identities he will not reveal. Last month, his company announced that it had ended talks with the Anbang Insurance Group, a Chinese financial firm linked to leading members of the ruling Communist Party. The potential agreement, first disclosed by The New York Times, had raised questions because of its favorable terms for the Kushners.

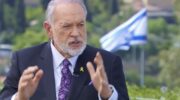

Beny Steinmetz (center, with gray tie) and his brother, Daniel, (gold tie) at a Vanity Fair party at the Natural History Museum in London in 2005. CreditDafydd Jones

Dealings with the Steinmetz family could create complications for Mr. Kushner. The Justice Department, led by Trump appointees, oversees the investigation into Beny Steinmetz. Even as Mr. Kushner’s company maintains extensive business ties to Israel, as a top White House adviser, he has been charged with leading American efforts to broker peace in the Middle East as part of his broad global portfolio.

“Mr. Kushner continues to work with the Office of the White House Counsel and personal counsel to ensure he recuses from any particular matter involving specific parties in which he has a business relationship with a party to the matter,” said Hope Hicks, a White House spokeswoman.

‘A Terrific Partner’

Representatives for Mr. Kushner and the Steinmetzes put distance between Raz Steinmetz and his uncle, Beny. Risa Heller, a spokeswoman for the Kushner Companies, called Raz “a terrific partner,” and added: “He is the only Steinmetz that we have done business with.”

In a statement provided by his attorney, Raz Steinmetz said: “None of my investment entities has invested in any transactions with Beny Steinmetz or any of his interests.” Louis Solomon, an attorney at Greenberg Traurig LLP, who represents one of Beny Steinmetz’s companies, said any business relationships between Raz and Beny were two decades old, and said the two men had not had contact since 2013.

The two men, as well as Daniel Steinmetz, who is Beny’s brother and Raz’s father, have controlled their own companies. But some of their financial interests — ranging from diamonds to real estate — have been entwined over the years. Records reviewed by The Times show that they have shared offshore investment vehicles, employed the same company director and were once connected to the same Swiss bank accounts.

The Justice Department would not comment on the inquiry. But more information about the bribery investigation may be disclosed by federal prosecutors at a trial that began Monday in New York. Mahmoud Thiam, Guinea’s former minister of mines, is facing corruption charges involving a Chinese company. An affidavit from a Federal Bureau of Investigation agent made public in the case last month said that the minister bribed a fellow government official “on behalf of” one of Mr. Steinmetz’s companies in 2009. The F.B.I. is also examining an alleged bribery episode involving a prominent Guinean — the late president’s wife — and a Steinmetz company a year earlier.

A Billionaire’s Legal Troubles

Until a few months ago, when he was arrested in Israel, Beny Steinmetz, 61, was a globe-trotting billionaire. One of the country’s richest men, he split his time between France, Geneva, Antwerp and his enormous house outside Tel Aviv, on a cliff overlooking the Mediterranean.

He teamed up with his brother Daniel, now 79, to create the Steinmetz Diamond Group in the 1990s. The business, which sells under the brand Diacore, has become one of the world’s biggest buyers of diamonds from De Beers. In April, a 59.6 carat pink diamond cut by Diacore was sold by Sotheby’s for $71.2 million, an auction record for a gem.

Beny Steinmetz expanded his business interests into steel, gold, nickel, oil and iron ore, and built a global real estate empire, with properties in cities including London, New York and St. Petersburg. Two decades ago, he made a move into Russia, becoming an early investor in newly privatized state enterprises as a co-founder of the hedge fund Hermitage Capital.

Mr. Steinmetz rarely grants interviews and often incorporates his multiple companies in tax havens like Guernsey, Cyprus and the British Virgin Islands that offer secrecy. Although he is the public face of his firms, he holds no executive position. Instead, they are typically owned by a Liechtenstein foundation — similar to a trust in the United States — that names him and his wife as beneficiaries. Officially, he is an “adviser” to his firms.

His legal problems stem from a huge deposit of iron ore in Guinea, in West Africa. In 1997, the Australian mining firm Rio Tinto was awarded exploration rights. But by 2008, the Guinean government was complaining that the project had taken too long, and it awarded half the rights to a Steinmetz firm, BSG Resources. In 2010, BSG sold half of that share, cutting a $2.5 billion deal with the Brazilian mining giant Vale.

In 2014, the Guinean government alleged that Mr. Steinmetz’s company had obtained the rights through corrupt practices, paying more than $8 million in cash through a representative to Mamadie Touré, then the wife of the dictator Lansana Conté. The Department of Justice had already opened an investigation the year before into Mr. Steinmetz’s firms for potential violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, claiming jurisdiction because some of the alleged payments were transmitted through American banks.

This month, lawyers acting on behalf of two of Mr. Steinmetz’s firms sued the billionaire financier George Soros in federal court in New York, asserting that he had directed a smear campaign against the companies. Mr. Soros has funded a portion of the Guinean government’s investigation, as well as work by the nonprofit Global Witness.

The Buying Spree

In 2012, Jared Kushner’s company went on a buying spree, snapping up about 11,000 apartments around the country, roughly doubling its inventory. The firm, founded by his father, Charles, also made its first Steinmetz deal that summer.

The younger Mr. Kushner has traveled repeatedly to Israel, where he has gotten funding to fulfill his ambitions. Kushner Companies has taken out at least four loans from Israel’s largest bank, Bank Hapoalim. It joined with Harel, one of Israel’s largest insurance companies, on one deal. Mr. Kushner’s firm was introduced to the Raz Steinmetz team “by a third-party broker in the United States,” said Kenneth Henderson, a New York attorney for Raz Steinmetz.

Beny Steinmetz and his wife, Agnes, in Tel Aviv in 2010.Credit David Bachar/Associated Press

In August of 2012, the Kushner business made a significant move into downtown Manhattan’s residential market, spending about $60 million on eight apartment buildings in the East Village and the West Village. The low-rise buildings are undistinguished but offer steady income streams.

The deal was arranged by Gaia Investments Corporation, headquartered outside of Tel Aviv. No Steinmetz names appear in Gaia’s public filings. Instead, the shareholders and officers include some Steinmetz lieutenants. One of them, Shlomo Meichor, was a former vice president for finance at an investment firm once run by Raz and Daniel Steinmetz, and is a director for at least three Gaia Delaware entities created for the Kushner deals, records show. (Gaia is an ancient Greek word for earth goddess.)

Gaia’s representatives have told prospective partners that the firm invests money for Daniel as well, according to two people familiar with those conversations. Mr. Henderson, the attorney, said Daniel Steinmetz was not involved in the Kushner investments.

The deals came amid an unprecedented flow of overseas cash into American properties, much of it through opaque corporations and limited liability companies that make the funds difficult to trace.

A Concerted Push for New York Area Property

Jared Kushner and the Steinmetz family have purchased numerous properties in the New York City area together, spending around $188 million for about two dozen buildings in Manhattan and New Jersey.

Beny Steinmetz’s legal problems began to surface a few weeks after the first investment with the Kushner company. In November 2012, The Financial Times reported on the Guinea bribery investigation, setting off coverage around the world.

The Kushner Companies made an even bigger deal with the Raz Steinmetz team a few months later, in January 2013, spending about $130 million on a portfolio of 17 apartment buildings across Lower Manhattan.

A few weeks later, a BSG Resources representative named Frederic Cilins — meeting in a diner at the Jacksonville, Fla., airport — urged Ms. Touré, by then the widow of the Guinean president, to destroy paperwork documenting the alleged bribes. She was cooperating with the F.B.I., though, and wearing a wire. Mr. Cilins pleaded guilty to obstructing a federal criminal investigation and was sentenced to two years in prison.

Beny Steinmetz has said he had no knowledge of Mr. Cilins’ activities.

In October 2013, a few days after Guinea moved to revoke its iron ore contracts with Mr. Steinmetz’s firms, his company’s representatives wrote their lawyers that he had transferred his diamond company stakes to his brother Daniel’s foundation in Liechtenstein. That disclosure is in the so-called Panama Papers, the trove of documents obtained by the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and reviewed by The Times through a collaboration organized by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

Corporate and bank records point to interlocking financial relationships among the Steinmetz family members in the past. Raz once managed the family’s real estate investments and participated in the family diamond business. As part of the bribery investigation involving Beny, Swiss prosecutors searched the offices of a company used by Daniel Steinmetz. The three men were once connected to at least two Swiss bank accounts at HSBC, according to bank records obtained by the French newspaper Le Monde and shared by the journalist consortium.

Mr. Solomon, the attorney for Beny Steinmetz’s firm, said that there was no current connection to Raz through any Swiss bank account. He said an Israeli investment vehicle that public records show Raz, Daniel and Beny still own jointly is “dormant.”

Risa Heller, the Kushner Companies spokeswoman, declined to discuss any due diligence the firm may have performed ahead of the investments.

The Kushner Companies appear to have carried out a public scrubbing of its Steinmetz associations. In late 2014, the Gaia name and logo disappeared from the Kushner website’s list of partners, where it had appeared since early 2013.

But the Kushners have not stopped making deals with the Steinmetz family. Around the time Gaia was dropped from the website, it invested in yet another Kushner building: a Trump-branded luxury high-rise in Jersey City. The $200 million project, known as Trump Bay Street, is at 65 Bay Street.

Jared Kushner’s ethics disclosure filed last month revealed a stake in a company called 65 Bay L.L.C. The entity was originally called GAIA JC LLC.