The Israeli kibbutz settlements that surround Gaza are built on stolen land. About 80 percent of Gaza’s population are families Israel violently expelled, caged in one small corner of their original lands for over 75 years.

The residents of these Israeli kibbutzes and “farming communities” on the perimeter of Gaza have been able for years to prosper, swim in pools, dance, sing and celebrate “unity and love” in large concerts just a few kilometers away from where over 2.1 million people live on 365 squared kilometers, usurped from their lands, subjugated to daily humiliation, purposely impoverished and caged in, unable to move, live, fish in the sea, and certainly unable to celebrate “unity and love.”

And all of this is largely hidden from the world, especially the ruthless, lethal violence by which Israeli forces wiped out their villages and stole their land – and the accompanying atrocities committed by Israeli soldiers.

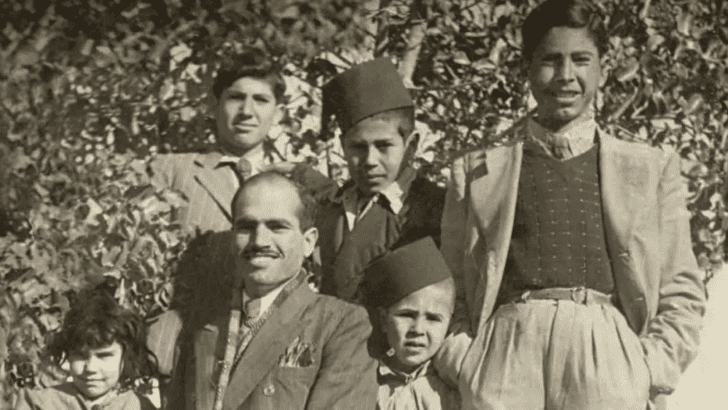

For example, Nirim, now in the news about the Gaza prison break, was the site of a gang rape in which 17 Israeli soldiers raped and then killed a Palestinian girl:

“The victim, a 10 to15-year-old Palestinian girl, was given a bath and a haircut in full view of the platoon’s members before they serially raped her, (which, it must be admitted, was decided democratically by a vote at the mess hall during that Saturday eve gathering in Kibbutz Nirim, newly established on Abu Sitta’s private land). Later, they execute the girl and bury her body in a shallow grave.” (See second article below)

by Perla Issa, reposted from Institute of Palestine Studies

If you are to read Western news reports coming from Israel, you would likely believe that Kfar Azza, Be’eri, Erez, Nahal Oz, and the other settlements that surround Gaza are “idyllic spots,” “little pieces of paradise, little pieces of heaven;” and “small farming communities.”

What is missing from this picture, what is missing from the vast majority of Western news reports on the genocide unfolding in Gaza is that these “pieces of paradise” are built on stolen land — stolen by Zionists from the Palestinian people through violence. And that the Palestinian population have been huddled and caged in one small corner of their original lands for over 75 years. That is what is currently called the Gaza Strip. About 80 percent of Gaza’s population are refugees, refugees from what today is called the Gaza perimeter. As Palestinian resistance increased over the years, as Palestinians, generation after generation, have tried to break the cage and return home, that cage has become tighter and tighter.

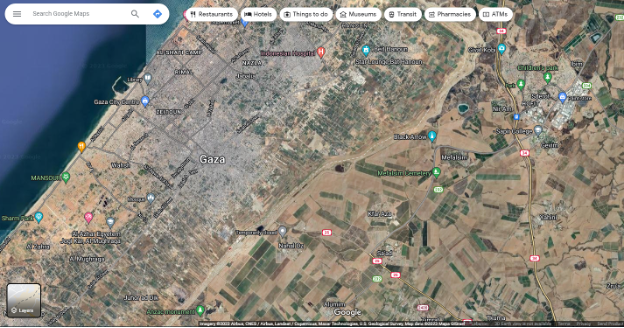

That is how the Israeli residents of these “farming communities” — around 50,000 people living on 1,038 squared kilometers of stolen lands (the Sha’ar HaNegev, Eshkol, and Sdot Negev regional councils)— have been able for years to live, prosper, raise families, have dinners, swim in pools, dance, sing and celebrate “unity and love” in large concerts just a few kilometers away from where over 2.1 million people live on 365 squared kilometers, usurped from their lands, subjugated to daily humiliation, purposely impoverished and caged in, unable to move, live, fish in the sea, and certainly unable to celebrate “unity and love.”

A simple glance at Google maps puts this reality in plain sight. How can such an urban reality exist? A people density of 5,753 people per squared kilometer next to a people density of 48 people per squared kilometer. Can there be any doubt that in order to keep such a reality for decades a vast amount of daily violence needs to be applied in order to prevent any spill over?

Palestinians live this reality on a daily basis, while Israelis, living in “idyllic spots,” thought that they could afford to forget it. They thought they could afford to forget how they came to live on that very land.

Let us here, remind ourselves of this reality.

In an oral history project of interviews with Zionist fighters, the truth is spoken plainly and simply. Michael Cohen from the Negev Brigade of the Israeli Occupation Forces (Formed from the Palmach, the elite fighting force of the Haganah) explains in a recorded video how the brigade expelled Palestinians in October 1948 from what “today you would call the Gaza Perimeter. It’s the entire Western sector bordering on today’s Gaza Strip.” He explains how “expelling was easy.” That the majority of the Palestinians “had no plans to hurt us” but that “we couldn’t allow ourselves, we, as an army and the [Jewish] settlements around us, to leave Arab settlements in our underbelly. We kicked them out.”

He explains how in many places, Palestinians left without a fight: “On one or two occasions, there was some sort of resistance, even using firearms. But that was rare … The Negev was cleared of all villages!” But with time the soldiers realized that the people they had expelled were coming back and that “it was difficult to finish the job with them.” He explains that they had to block them, “block means shoot to kill!” In his own words: “So in that case I saw it with my own eyes, I didn’t just see it with my own eyes, I also did it. Expulsion was one thing that needed to be done and it was done.”

Indeed, violent expulsion was done, but violence breeds violence. Through Cohen’s testimony we can see how Palestinian resistance was changing and adapting in response to Israeli violence. The villagers and Bedouins went from friendly coexistence, to acquiescence, to non-violent resistance by quietly returning to their lands, but once faced with deadly force, they resorted to armed resistance, they started attacking roads and planting mines. The Israeli response was more violence, they demolished Palestinian homes and burned fields forcing the population to flee again. Cohen explains how they planted explosives and “would topple down the houses in one full swoop.” He further explains: “The demolition [of the houses] and/or the burning of the fields, it wasn’t a one-time thing during the deportation, it was a process.”

Avri Ya’ari of the Haganah explains in another recorded video how they expelled the people of Huj (هوج), a Palestinian village lying 2.5 kilometers from the current Israeli settlement of Sderot and 6.5 kilometers from the Gaza Strip; where Ariel Sharon built a ranch. Through Ya’ari’s testimony we get a sense of the large disproportionate of force between the Israeli armed forces and the Palestinians and again we see how the Palestinian population was peaceful.

Ya’ari: There was Huj … but the relations with them were very good …

Interviewer: The Arab population, when did they leave the area?

Ya’ari: When they were told to. [Laughter]

Interviewer: What do you mean?

Ya’ari: They were told to take a hike.

Interviewer: Who told them?

Ya’ari: The army, the Israeli Defense Forces. In certain stages … how should I say it? They cleared the area of Arabs. The people of Huj, who had been very friendly and later suffered terribly in the refugee camps, they told them, they’d be back in two or three weeks.

Palestinians indeed have been attempting to return ever since by any and all means at their disposal. Therefore, if you wish to help end the violence, to usher in peace and security for Palestinians and Israelis, then recognize what lands Israeli settlements have been built on and call them by their names, their real names. In the table below is a list of some of the settlements that surround Gaza and the corresponding Palestinian lands that they have been built on, whether it be city, village, or tribal lands.

|

Israeli settlement |

Name of depopulated Palestinian city that corresponding Israeli settlement is built on | Name of depopulated Palestinian village that corresponding Israeli settlement is built on | Name of depopulated Tribal land that corresponding Israeli settlement is built on | Additional notes from author |

| Ashkelon | Al-Majdal (المجدل)

Al-Jura (الجورة), Al-Khisas (الخصاص), Ni’ilya (نعليا) |

Built on the village lands and orchards | ||

| Zikim | Hirbiya (هربيا) | Built on the citrus groves of the village | ||

| Karmiya | Hirbiya (هربيا) | Built on the orchards of the village | ||

| Mavqiim | Barbara (بربرة) | Built on the village and its orchards | ||

| Erez | Dimra (دمرة) | |||

| Sderot | Najd (نجد) | |||

| Mefalsim | Wadi ez Zeit of Gaza city | |||

| Kfar Aza | Turkman quarter of Gaza city | |||

| Nahal Oz | Waqf Esh Sheikh Zarif in Gaza city (وقف الشيخ ظريف) | |||

| Sa’ad | Jdeide quarter of Gaza city | |||

| Alumin | Turkman quarter of Gaza city | |||

| Be’eri | Wuhaitat al Tarabin (الوحيدات ترابين) clan of the Tarabin (ترابين) tribe lands | |||

| Re’im | Ghawali al-Zari’i (غوالي الزريعي) clan of the Tarabin (ترابين) tribe lands | Built next to the ancient ruins of Tell Jamma (تل جمة) in the Gaza valley | ||

| Kisufim | Abu Khammash (ابو خماش) clan of the Tarabin (ترابين) tribe lands | |||

| En HaShlosha | Ma’in Abu Sitta village (معين ابو ستة), Umm Tina hamlet (ام تينة) | part of the Arab al Ghawali (عرب الغوالي) clan of the Tarabin (ترابين) tribe | Umm Tina is described in an oral history project by a former villager as “fertile land extending as far as the eye can see, wide and spacious, with almond orchards and fields of wheat, barley, lentils, watermelons, and cantaloupes … a wonderful country.” | |

| Nirim | Ma’in Abu Sitta village (معين ابو ستة), | part of the Arab al Ghawali (عرب الغوالي) clan of the Tarabin (ترابين) tribe | Built on the ruins of the village’s former school | |

| Nir Oz | Ma’in Abu Sitta village (معين ابو ستة), | part of the Arab al Ghawali (عرب الغوالي) clan of the Tarabin (ترابين) tribe | Built on the village orchards | |

| Magen | Ma’in Abu Sitta village (معين ابو ستة), Abu Tailakh (أبو تيلخ) and Abu Nuqeira (ابو نقيرة) hamlets | Part of Arab al Ghawali (عرب الغوالي) clan of the Tarabin (ترابين) tribe | Built on the village orchards, engulfing the shrine of Sheikh Nuran (مقام الشيخ نوران ) and the Abu Qurayda spring (بئر أبو قريدة) | |

| Ami’Oz,

Zohar, Ohad, Mivtahim, Yesha |

Umm ‘Ajwe (أم عجوة) and Tell Rabiya (تل رابية) hamlets | Part of the Najmat clan (نجمات ) of the Tarabin (ترابين) tribe | ||

| Sde Nitsan,

Talmei Eliyahu |

Karm ‘Aqel (كرم عقل) | Part of the Najmat clan (نجمات ) of the Tarabin (ترابين) tribe | ||

| Holit | El-Buhdari hamlet (كرم البهداري) | Part of the Najmat al-Kassar (نجمات القصار) clan of the Tarabin tribe (ترابين) | Built on the village orchards | |

| Peri-Gan,

Sede-Avraham, Deqel, Talme-Yosef, Avshalom, Yated, Yevul |

El-Ahmar (كرم الاحمر) and El-Khilawi (كرم الخلاوي) hamlet | Part of the Najmat al-Kassar (نجمات القصار) clan of the Tarabin tribe (ترابين) | Built on the village orchards

|

Perla Issa is a researcher at the Institute for Palestine Studies in Beirut, Lebanon. The list above is not an exhaustive list. Feel free to contact the author directly at [email protected]. You may also seek additional resources such as All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948, the Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question (Places section), Palestine Open Maps, Palestine Remembered, and The Return Journey (Atlas) for further reading on the history of destroyed and depopulated villages across all of Palestine.

RELATED:

- Gaza Great March of Return

- Tracing Homelands: Israel, Palestine and the Claims of Belonging

- History

- WATCH: What was happening in Gaza BEFORE the Hamas attack that the media didn’t tell you?

- WATCH: Israel Palestine Basics

‘I Saw Fit to Remove Her From the World’

By Aviv Lavie, Moshe Gorali, reposted from Israeli newspaper Ha’aretz, Oct. 29, 2003

Documents obtained by Haaretz tell the long-hidden story of what Ben-Gurion described as a ‘horrific atrocity’: In August 1949 an IDF unit caught a Bedouin girl, held her captive in a Negev outpost, gang-raped her, executed her at the order of the platoon commander and buried her in a shallow grave in the desert. Twenty soldiers who took part in the episode, including the platoon commander, were court-martialed and sent to prison.

There was a particularly festive atmosphere at the Nirim outpost on August 12, 1949, the eve of Shabbat. A week of dusty patrols and pursuits of infiltrators in the sands of the western Negev desert was at an end, and the commander of the hilltop site, Second Lieutenant Moshe, gave the order to make the preparations for a party. The tables in the large tent that was used as a mess hall were arranged in rows, sweets of various kinds were laid out on them and even a bit of wine was poured, though not enough to get drunk on. At exactly 8 P.M. the soldiers took their places and platoon commander Moshe recited the blessing over the wine. He then gave a Zionist pep talk, reiterating the importance of the unit’s mission and the troops’ contribution to the infant state. At the order of his deputy, Sergeant Michael, Private Yehuda read from the Bible. When he finished the soldiers burst into song, told jokes, ate and drank. A merry time was had by all.

Shortly before the end of the party, at about 9:30, the platoon commander asked for quiet. He got up and, with a smile on his face, reminded the soldiers about the Bedouin girl they had caught earlier that day during a patrol in their sector. They had brought her to the outpost and she was now locked up in one of the huts. Platoon commander Moshe said he was putting forward two options for a vote. The first was that the Bedouin girl would become the outpost’s kitchen worker; the second was for the soldiers to have their way with her. The proposals got an enthusiastic reception. A melee ensued. The soldiers raised their hands and the second option was accepted by majority vote. “We want to fuck,” the soldiers chanted. The commander decided on the order: Squad A on day one, Squad B on day two and Squad C on day three. The driver, Corporal Shaul, asked jokingly, “And what about the drivers? Are they orphans?” The platoon commander replied that they were part of the staff squad, together with the sergeant, the squad commanders, the cooks, the medic and he himself, of course. He added a threat – if any of the soldiers touch the girl “the tommy [tommy gun] will talk.” The soldiers took this as a warning not to violate the order the commander had decreed.

The party ended, the soldiers went off to their tents. The officer ordered the platoon sergeant to bring a folding bed to the tent they shared and to place the Bedouin girl on it. Sergeant Michael did as he was told, entered the tent, closed the flap and shut off the lantern.

Thus began one of the ugliest and most appalling episodes in the history of the Israel Defense Forces. Even at a remove of 54 years, it is difficult to understand how an event of this kind could have happened with the participation, active or less active, of dozens of soldiers in uniform.

Low professional and moral level

The IDF of 1949, still in its infancy and called upon to defend the borders of the newborn state, found itself having to cope – not always successfully – with the rapid absorption of a very large number of untrained soldiers, especially those who were sent to the front immediately after disembarking from the ship in which they had arrived in Israel. “A rabble of new immigrants with a low professional and moral level,” was the blunt description offered by the special military court in its verdict on the episode of the Nirim outpost.

Yehuda (his full name, as well as the names of others who were interviewed for this article, are in the possession of Haaretz) was one of the soldiers serving in the outpost in August 1949. He is now a 74-year-old pensioner who lives in the north. He accepts the description of the group as a “rabble”: “I was then 20 years old,” he says. “I ran away from the Turkish Army to Palestine and immediately enlisted. I remember that all the members of our battalion were new immigrants. Everyone was from a different country: Algeria, Hungary, Romania, Tunisia, Turkey, Morocco. We didn’t know Hebrew, we communicated between us by sign language. We did our basic training at the Dead Sea. We were taught how to hold a rifle in a mess hall at Sodom. Then we were sent to the outpost, where we did patrols or trained in the trenches and practiced rushing to our positions.”

Yehuda remembers the night of the party, but claims that he was then on guard duty and that he heard the story about the vote and what happened afterward only as a rumor. Together with 17 members of the platoon he was court-martialed for “negligence in preventing a crime.” He was sentenced to four years in prison; his term was cut in half by the appeals court.

Yitzhak, who is the same age as Yehuda and now lives in the center, received the same punishment. He, too, had arrived in Israel a few months before the summer of 1949, and he did not know Hebrew. Today he is retired and has health problems. “I remember being in the Negev but I can’t even remember the name of the unit. I had just arrived in the country, I looked like a boy, I did a lot of guard duty. I had forgotten about that whole affair, I don’t remember a thing, I haven’t thought about it for maybe 50 years. The only reason I was tried was that I was in the outpost when it happened. Beyond that I don’t remember a thing and I have nothing to say. Was I angry at those who did it? What would it help me to be angry?”

The developments in the IDF after the War of Independence may furnish a partial explanation for the chain of events that is described in this article; but no more than a partial explanation. After all, the platoon commander, Moshe, who spearheaded the affair, was not part of the “new IDF.” “The officer and the sergeant were veteran Israelis and spoke fluent Hebrew,” Yehuda recalls. As far as is known, Moshe served in the British Army and afterward in the 8th Brigade under the command of the legendary Yitzhak Sadeh in what was the only IDF armored brigade in the War of Independence. The brigade was disbanded after the war and its officers and soldiers were reassigned to various units. Officer Moshe was sent to the Negev.

The Negev Region Command was established after the War of Independence. It was a regional command and its assignment was to secure the lengthy new border line between Israel and Egypt. The staff headquarters were located in Be’er Sheva, and the units were deployed in outposts along the border with the aim of preventing the infiltration of Bedouin from the Egyptian desert. The military historian Meir Pa’il, a retired colonel, was appointed operations officer of the Negev Region in December 1949, four months after the events with which this article deals. Pa’il: “The Negev was sparsely populated. We were barely able to cobble together one reserve battalion from all those who lived in the settlements in the region. In order to man the border line, units were sent on a rotating basis from other regions, such as the Golani Brigade, the 7th Brigade and so forth. In addition to preventing infiltrations, there was also an effort to remove as many Bedouin as possible from the country – from the Halutza Dunes area, for example. It was a kind of cleansing across the Egyptian border. The tribes who had cooperated during the war were left where they were; those who were hostile were expelled.”

One of the battalions of the Negev Region was known as the Sodom District Battalion. The battalion was originally in charge of the Dead Sea and Arava area, but at the beginning of August 1949 it was moved to the Bilu Junction, near Rehovot, where it waited a few days for new orders. The battalion commander was Major Yehuda Drexler, who was nicknamed “Idel.” Over the years, Drexler, afterward a leading architect, worked for the Jewish Agency, was one of the planners of Kibbutz Sde Boker in the Negev (Ben-Gurion’s kibbutz) and reached the rank of department head in the Israel Lands Administration. One of the company commanders in the battalion was Captain Uri.

On August 8, his company was ordered to move south to man the outposts in the western Negev. The platoons were stationed at three kibbutzim: Be’eri, where the company headquarters and Captain Uri himself were stationed, Yad Mordechai and Nirim. Platoon 3, headed by the new commander, Second Lieutenant Moshe, who had been given command of the unit only a few days earlier, was sent to the Nirim outpost, which was responsible for the most remote and most dangerous sector – adjacent to the border with Egypt. Sergeant Michael was the deputy commander of the platoon.

On the eve of the move south, the company commander, Captain Uri, briefed the soldiers. Intelligence reports received from aerial patrols over the western Negev mentioned two Bedouin tribes that had been spotted in the sector. “You are to shoot to kill at any Arab in the territory of your sector,” the company commander said. Moshe asked for the operational order in writing, as customary. The company commander promised to bring the written document to the outpost at a later date.

Platoon 3 reached Nirim on the afternoon of Tuesday, August 9. The infrastructure of the camp was quickly put in place: three large tents as the soldiers’ quarters, a small tent for the officer and the sergeant, and a big tent as the mess hall. In addition, there was a small hut that served as the office of the platoon’s headquarters and another hut, unused, which would play a central role in the episode.

In the summer of 1949, there was no longer any connection between Kibbutz Nirim and the outpost of the same name. The outpost bore the name Nirim because it was situated at the place where Kibbutz Nirim was originally established, in June 1946. The young kibbutz, which was located on the edge of the desert, fought for its survival in the harsh climatic conditions of the area and became the first settlement to be attacked on the first day of the War of Independence, on May 15, 1948. The Egyptians, with a force that included an artillery battalion, an infantry battalion and dozens of armored vehicles, launched a heavy barrage that caused immense damage: all the buildings of the kibbutz were burned to the ground, the animals died, and eight kibbutz members were killed and four wounded (of a total of 39 members). The barrage was followed by an assault mounted by hundreds of infantry soldiers, who reached the fence of the kibbutz. The kibbutzniks, firing from their trenches, inflicted heavy losses on the Egyptian force and miraculously the attack ended. The Egyptians changed their mind and decided to forgo the pleasure of infiltrating and capturing the kibbutz. Instead, they simply went around it on their way north.

The Nirim group spent the war in shelters and caves that they dug. When the hostilities ended and they were finally able to come to the surface in safety, they entered into talks with the army and the state authorities. There was a confluence of interests: the army coveted the site because of its strategic location; the kibbutzniks wanted to move north, to the line of 200 millimeters of rain a year.

In March 1994 the kibbutz moved about 15 kilometers north, to its present location. The IDF took over the terrain-dominating outpost, which was henceforth known as “Old Nirim,” or “Dangour,” as it was originally called – the name still appears on some maps – apparently after an Egyptian Jew who purchased land in the area. There is now a monument of rough concrete at the site that commemorates the kibbutz members who were killed in the Egyptian assault on the first day of the 1948 war. The monument bears an inscription: “It is not the tank that will triumph, but man.” If you climb the monument and look west, you can see the rooftops of Khan Yunis.

The commander orders an execution

On Tuesday, August 9, the platoon organized itself at the outpost. The soldiers soon got used to the ways of the new commander. Second Lieutenant Moshe turned out to be a strict disciplinarian who demanded order and obedience. The soldiers had to dress properly and shave every day. Anyone who violated the orders was hauled before Moshe. The soldiers were apparently somewhat in awe of him. The next day the company commander, Captain Uri, visited the platoon. The first couple of days passed uneventfully. Until the morning of Friday, August 12.

At about 9 A.M. that day, Second Lieutenant Moshe set out on a patrol in the southwestern section of the sector, in a vehicle known as a “command car.” With him were two squad commanders, Corporal David and Corporal Gideon, and three soldiers: privates Moshe, Yehuda and Aziz. The driver was Corporal Shaul. All the men were armed.

On the way they came across an Arab who was holding an English rifle. When the Arab spotted them he threw down the rifle and started to run up the dune. One of the soldiers opened fire at him with a submachine gun. The Arab was hit and died on the spot. His rifle was taken as booty.

A short time later, the patrol encountered three Arabs – two men and a girl. There are different versions regarding the girl’s age. According to some accounts she was a young girl aged between 10 and 15; others say she was between 15 and 20. Platoon commander Moshe ordered the soldiers to seize the Arabs and search them. The soldiers found nothing. Officer Moshe then ordered the soldiers to bring the girl into the vehicle. Her shouts and screams were to no avail. Once she was inside the vehicle the soldiers scared off the two Arabs by shooting in the air. On the way back to the outpost they came across a herd of camels grazing. Officer Moshe ordered the soldiers to shoot the animals. Six camels were shot dead; their carcasses were left to rot in the field.

After the girl calmed down a bit, the soldiers exchanged a few words with her – especially Corporal David. They also talked among themselves, and the word “fuckable” came up in the conversation. The patrol returned to the outpost in the afternoon. At about the same time, another vehicle also arrived at the outpost: the battalion commander, Yehuda Drexler, was paying a visit, He was accompanied by Captain Mordechai (Motke) Ben Porat, operations officer of the Negev Region. Ben Porat eventually reached the rank of brigadier general in the Armored Corps and after his retirement from the army served as chairman of the National Parks Authority.

At the outpost, the soldiers removed the girl from the vehicle. Officer Moshe ordered that she be taken to the unused hut and a guard placed at the door. Private Avraham was designated the guard. Drexler, who noticed a certain commotion around the girl, asked what she was doing there. Officer Moshe replied that on the patrol he had encountered her and her husband, who was armed with a rifle. He told Drexler that they had killed the husband and taken the girl prisoner in order to interrogate her about the location of her tribe. Drexler authorized her interrogation but ordered that afterward she be taken back to the place where she had been seized, and released. He also asked platoon commander Moshe to ensure that the soldiers did not abuse her. Drexler and Ben Porat spent about two hours at the outpost, had lunch and left.

Shortly after their departure, Officer Moshe went out on another patrol, this time in the northern sector, in the direction of the new location of the kibbutz. After he had left, the platoon sergeant, Michael, removed the girl from the hut and pulled off the traditional garment she was wearing. He then made her stand, completely naked, under the water pipe that the soldiers used as a shower, then soaped her and rinsed her off. The pipe was outside and everyone at the outpost was able to witness the spectacle.

After the shower was over, Sergeant Michael burned the girl’s dress and dressed her in a purple jersey and a pair of khaki shorts. Now looking like a regular Palmach commando, she was taken back to the hut and placed under the guard of Private Avraham. In short order a group of soldiers gathered around the hut. They milled around the guard and demanded that he let them go inside. At first he refused, but finally relented. In fact, he was the first to go in. He spent about five minutes in the hut and emerged buttoning up his trousers. He was followed by Private Albert, who was also in the hut for about five minutes, and then Private Liba.

Liba was still in the hut when platoon commander Moshe returned from the patrol. A few soldiers shouted a warning to Liba, who ran out of the hut and disappeared. Officer Moshe apparently understood what had happened, conducted a quick debriefing, and afterward, in the dining room, was heard to say that “three soldiers raped the Arab girl.” He ordered her to be brought to the staff hut. The squad commanders, Corporal David and Corporal Gideon, were present in the hut. Officer Moshe took note of the girl’s new apparel but said nothing. She told him, in Arabic, that the soldiers “played with her.” It was obvious to Moshe what she meant. Corporal Gideon, who would be one of the main prosecution witnesses in the trial, testified that after the girl told Officer Moshe what she told him, he said to the others that she must be washed so she would be clean for fucking. Gideon, who lives in Givatayim and works as a tour guide, declined to be interviewed for this article.

At about 5 P.M., the platoon commander ordered Private Moshe, who was a barber by profession, to give the girl a haircut. That was done in the presence of the commander and the sergeant. Her hair, which had spilled down to her shoulders, was cut short and washed with kerosene. Again she was placed under the pipe, naked, before the scrutinizing eyes of the officer and the sergeant. Afterward she was dressed in the same jersey and shorts and sent back to the hut.

Then came the party, after which Officer Moshe and Sergeant Michael closeted themselves with the girl in their tent. After about half an hour, Officer Moshe ordered her taken out of the tent, because “there is a stink coming off her.” Sergeant Michael called Private David and the two of them removed the bed from the tent, with the girl lying on it in a state of unconsciousness. They carried the bed to the entrance of the hut. Michael placed the girl on the floor, went to get water and poured the water on her. He then carried her in his arms into the hut. Corporal David accompanied him.

At about 6 A.M. the next day, Private Eliahu was on guard duty and saw the girl leaving the hut. He asked her where she was going and she told him, weeping, that she wanted to see the officer. Private Eliahu showed her the way to Officer Moshe’s tent. She complained to him that the soldiers had “played with her.” He threatened to kill her and sent her back to the hut. A short time later, while shaving at the water pipe, Sergeant Michael asked the platoon commander what to do with her. Officer Moshe ordered him to execute the girl.

Michael ordered Corporal David to have two soldiers get shovels and accompany him. Michael and David removed the girl from the hut and had her get into the patrol vehicle. Just before the vehicle left the outpost, one of the soldiers shouted that he wanted back the short pants the girl was wearing. Officer Moshe ordered her to be stripped and the pants returned to the soldier. She now wore only the jersey, her lower body exposed.

Eliahu and Shimon dig a grave

The vehicle set out, driven by Corporal Shaul. Also in the vehicle were Sergeant Michael, Corporal David, the medic, and the two soldiers who were to be the gravediggers, Privates Eliahu and Shimon, with their shovels. They drove about 500 meters from the outpost. The driver, Shaul, stayed in the vehicle, while the others, with the girl, moved off a little way into the dunes. Privates Eliahu and Shimon set about digging a grave. When the girl saw what they were doing, she screamed and started to run. She ran about six meters before Sergeant Michael aimed his tommy gun at her and fired one bullet. The bullet struck the right side of her head and blood began to pour out. She fell on the spot and did not move again. The two soldiers went on digging.

Sergeant Michael went back to the vehicle. Pale and trembling, he laid down his weapon and said to Shaul, “I didn’t believe I could do something like that.” Shaul said that maybe the bullet didn’t kill her and that she was liable to lie in torment for a few hours, buried alive. He asked Michael to do him a personal mercy by going back to the girl and shooting her a few more times, to ascertain that she was dead. The sergeant did not manage to carry out that mission. Corporal David came over, took the tommy gun and fired a few bullets into the girl’s body. The pit the privates dug wasn’t very deep, only about 30 centimeters. They placed the body in the pit, covered it over with sand and returned to the outpost.

That afternoon the company commander, Captain Uri, visited the outpost. Not finding Second Lieutenant Moshe at the site, he left the written operation order that Moshe had requested with the platoon sergeant. Officer Moshe was then on his way to Be’er Sheva. It was Saturday night and he was on his way to see a movie. At the movie theater he met the battalion commander, Drexler. Drexler asked whether the Bedouin girl had been taken back to the place where she was found. Officer Moshe said she hadn’t: “They killed her,” he said, “it was a shame to waste the gas.” Drexler said nothing but the next day ordered the company commander to go to the outpost and find out exactly what happened there.

Even before he received the order, Captain Uri, who had heard rumors about the events at the outpost, asked Officer Moshe for a report about what had happened with the Arab girl. Moshe ordered Sergeant Michael to draw up the report in his handwriting. When the report was completed, Officer Moshe signed it and sent it to the company commander. The following is the report, dated August 15, 1949:

“Nirim Outpost. To: Company Commander. From: Commander, Nirim Outpost.

Re: Report on the captive

In my patrol on 12.8.49 I encountered Arabs in the territory under my command, one of them armed. I killed the armed Arab on the spot and took his weapon. I took the Arab female captive. On the first night the soldiers abused her and the next day I saw fit to remove her from the world.

Signed: Moshe, second lieutenant.”

More info here.