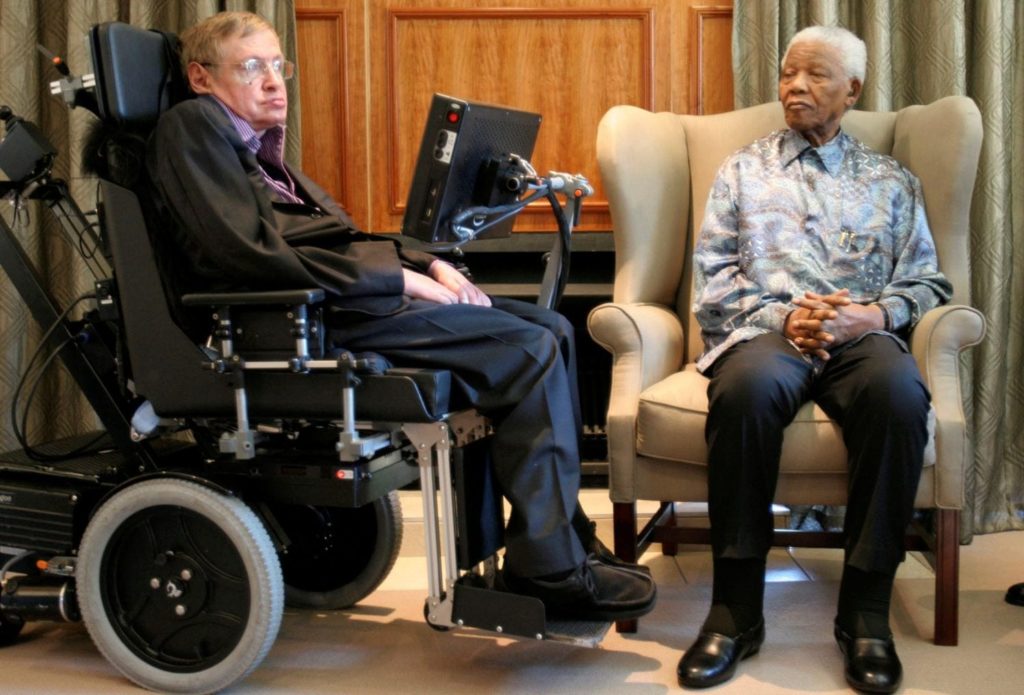

Stephen Hawking speaks to students at the Bloomfield Museum of Science in Jerusalem, December 10, 2006. Credit: AP

Stephen Hawking was critical of Israel and supported BDS, but also visited Israel a number of times and based his revolutionary theory on the works of an Israeli scientist

By Judy Maltz, Ha’aretz

Stephen Hawking, the world-renowned physicist who died on Wednesday, had a difficult relationship with Israel.

In 2013, his decision to boycott a conference in Jerusalem honoring Shimon Peres, the late Israeli president, made international headlines, sparking outrage in Israel and much of the Jewish world.

The conference, which was meant to mark the 90th birthday of the Israeli leader, was attended by world leaders and celebrities, among them former U.S. President Bill Clinton and former British Prime Minister Tony Blair. Hawking’s decision to back out was first reported in The Guardian.

Hawking initially notified the organizers that he would attend, but under pressure from the international Boycott, Divest and Sanctions movement, he reneged. At first, his associates said that Hawking would not be attending because of his failing health. Only later did it emerge that his decision had been prompted by pressure from the boycott movement.

In a letter to the conference organizers, Hawking wrote: “I have received a number of letters from Palestinian academics. They are unanimous that I should respect the boycott. In view of this, I must withdraw from the conference.”

Responding to his decision, the conference organizers issued an angry statement saying: “The academic boycott is in our view outrageous and improper, certainly for someone for whom the spirit of liberty lies at the basis of his human and academic mission. Israel is a democracy in which all individuals are free to express their opinions, whatever they may be. The imposition of a boycott is incompatible with open, democratic dialogue.”

Although many musicians and artists have declined to visit Israel as a way of showing solidarity with the Palestinians, Hawking was the first scientist of his stature to embrace the boycott movement.

Many opposed to his decision took to social media at the time to vent their anger, some accusing him of outright anti-Semitism and others going so far as to ridicule his physical condition. Much ado was made at the time of the fact that the computer-based system through which he communicates to the world runs on a chip designed by Israel’s Intel team.

Writing in Time Magazine then, David Wolpe, the prominent Los Angeles rabbi, voiced his indignation. “As Hawking must know,” he wrote, “he is boycotting precisely those most likely to agree with his political stance, the left-wing academic community in Israel. It’s hard to believe he endorses a theory that if he can make some academic conferences a tad less prestigious, peace will bloom.”

It was not the first time that Hawking had taken sides with the Palestinians against Israel. In 2009, in an interview with Al Jazeera, he condemned the recent Israeli military operation in Gaza, saying it was “”plain out of proportion… The situation is like that of South Africa before 1990 and cannot continue.”

As recently as last year, Hawking urged his millions of followers on Facebook to donate money to help finance a series of lectures in physics for Palestinian graduate students in the West Bank.

Hawking visited Israel four times, most recently in 2006, when as a guest of the British embassy in Tel Aviv, he delivered public lectures at Israeli and Palestinians universities.

Arguably the most famous scientist in the world, Hawking enjoyed a special relationship with a now-deceased Israeli physicist, Jakob Bekenstein, who died in 2015. Bekenstein, who was a professor at both Ben-Gurion University and the Hebrew University in Jerusalem before moving back to the United States, is considered to be the man who taught Hawking a thing or two about black holes. Hawking was initially one of Bekenstein’s detractors, but he eventually embraced the Israeli scientist’s groundbreaking ideas, which served as the basis for his own revolutionary theory that black holes give off radiation.