When Israel invaded Egypt 65 years ago during the Suez Crisis, President Eisenhower defended U.S. interests rather than enabling Israeli aggression…

Even though he was up for reelection, Eisenhower offered an exceptionally tough response:

“We cannot – in the world, any more than in our own nation – subscribe to one law for the weak, another law for the strong. There are some firm principles that cannot bend – they can only break. And we shall not break ours.”

‘We’ll Lose Some Israeli Votes,’ Nixon Said. ‘But We Kept American Boys Out.’

In private correspondences, Eisenhower accused Ben-Gurion of timing the invasion one week before the election out of a false belief that the president would fear “the Jewish vote.”

“We realized that he might think he could take advantage of this country because of the approaching election and because of the importance that so many politicians in the past have attached to our Jewish vote,” Eisenhower wrote…

“I gave strict orders to the State Department that they should inform Israel that we would handle our affairs exactly as though we didn’t have a Jew in America. The welfare and best interests of our own country were to be the sole criteria on which we operated.”

“American politics on Israel were very different back then… the toughest moments Israel experienced in its early relationship with the U.S., came under Republican presidents”…

By Amir Tibon, reposted from the Israeli newspaper Ha’aretz,

Richard Nixon, then the vice president of the United States, was in Detroit on the morning of October 31, 1956, when his staff connected him by phone with Secretary of State John Foster Dulles. The main subject was the crisis in the Middle East, where 48 hours earlier Israel had invaded Egypt and taken over the Sinai Peninsula, surprising America and shocking the world. Nixon asked the secretary to update him on the latest developments and the administration’s response.

Toward the end of their conversation, they discussed another issue just as urgent: the presidential election that was only seven days away. President Dwight Eisenhower was seeking reelection, and while he was comfortably leading in the polls, some members of his administration worried that his response to the Israeli invasion could harm him politically. Eisenhower had denounced Israel’s aggression and was moving to suspend U.S. economic aid to the young Jewish state. Dulles asked Nixon, “the expert” in his words on all things politics, if the president’s tough line could cost him at the ballot box.

“We will lose some Israeli votes,” Nixon replied, confusing America’s Jewish community with citizens of the far-away State of Israel. “But there aren’t many.” He added that more important than how Americans would judge Eisenhower’s criticism of Israel was the fact that “our policy is still one that has kept American boys out” of the Middle East.

1956 Israeli invasion of Egypt: ‘Operation Kadesh’

This week marks the 65th anniversary of Israel’s invasion of Sinai, known to Israelis as Operation Kadesh and to almost everyone else as the Suez Crisis. The invasion was part of a conspiracy with Britain and France to give the two European powers control over the Suez Canal and cripple the Nasser regime in Egypt along the way. It was a tactical military victory for Israel, which pushed back the Egyptian army with surprising ease, but a massive diplomatic blunder that ended in failure after Eisenhower refused to go along with the plan, threatened sanctions against Israel and eventually forced it to withdraw from all the territory it had conquered.

The events of 1956 were a strategic turning point in the Middle East. Daniel Kurtzer, a former U.S. ambassador to Israel and Egypt, says that the events represent “the last hurrah” of British and French domination in the region, as the two European countries were each exposed as “a spent power.”

The United States and the Soviet Union, Kurtzer adds, emerged from Suez as the most important players in the region, competing for influence and the acquisition of new allies.

But apart from the geopolitical ramifications, 1956 was also a rare moment in the history of the U.S.-Israel relationship. In Kurtzer’s words, it was “the most explicit threat of sanctions against Israel ever made by an American president.” Kurtzer notes that only two other events in the history of the relationship approached that level of tension: Gerald Ford’s “reassessment” in 1975; and George H.W. Bush’s conditioning of loan guarantees in 1991. [Editor’s note: see “When George Bush, Sr. took on the Israel lobby, and paid for it”]

Still, Kurtzer says, Eisenhower’s response in 1956 was different, even more so because it came just days before a crucial U.S. election.

On the same day Dulles heard from Nixon that, apart from “some Israeli votes,” the election wouldn’t be affected by the crisis, a senior State Department official called the Israeli ambassador, Abba Eban, to deliver a stark warning: “The secretary is now considering economic limitations which we believe it is necessary to impose on Israel,” said William C. Burdett, an experienced career diplomat. “Before making a final decision, the secretary would like to know the Israeli government’s intentions with respect to the withdrawal of its forces from Egyptian territory.”

War of necessity?

Israel presented the invasion as a defensive measure it had to take in response to terror attacks and a growing threat from the nationalist regime in Egypt. The administration made clear that it wouldn’t buy this explanation.

A day after the Burdett-Eban phone call, a summary of a meeting at the U.S. Department of Agriculture included the following lines: “Effective immediately all Public Law 480 aid to Israel was to be immediately discontinued … cargoes now being loaded or afloat would not be stopped but no further shipments should be made under existing contracts.”

Aid to Israel under the Public Law 480, better known as the Agricultural Trade Development and Assistance Act, was modest and not of any strategic importance to Israel at the time. But the decision signaled that Eisenhower meant business: Israel would have to withdraw its forces or America would halt various forms of assistance.

Eisenhower stands up for U.S. interests

A memo from Eisenhower that same day, as Israeli forces forged ahead on the ground, explained the reasoning behind his tough response. His most important consideration, according to the document, was the belief that Israel’s invasion would end up playing into the Soviets’ hands.

William Hitchcock, a historian at the University of Virginia and author of a 2018 Eisenhower biography, says the president was mainly concerned that the Soviets would use the invasion to increase support in countries that had recently won independence from the colonialist powers.

Eisenhower “understood very well that there were new tensions in the world at the time,” Hitchcock explains. “He was a man who had traveled the world and understood the politics of different continents, and he realized there was a north-south divide – a divide between new countries and the powers that used to rule over them.”

In his memo, Eisenhower wrote: “At all costs the Soviets must be prevented from seizing a mantle of world leadership through a false but convincing exhibition of concern for smaller nations. Since Africa and Asia almost unanimously hate one of the three nations Britain, France and Israel, the Soviets need only to propose severe and immediate punishment of these three to have the whole of two continents on their side.”

This logic, Kurtzer agrees, is what pushed Eisenhower to take a firm stand against Israel in his public statements, as well as at the United Nations, where his administration pushed for resolutions that denounced the invasion. According to Kurtzer, the president was also concerned that Israel, France and Britain’s moves would legitimize the Soviet invasion of Hungary, which took place at the exact same time as the Suez crisis, and drive the world’s focus away from the streets of Budapest.

In a letter to then-Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, Eisenhower also highlighted his administration’s commitment to the world order that was constructed after World War II – an order he helped create as supreme Allied commander during the war, and which rested on adherence to the decisions of international bodies like the UN.

“Statements attributed to your Government to the effect that Israel does not intend to withdraw from Egyptian territory, as requested by the United Nations, have been called to my attention,” Eisenhower wrote. “I must say frankly, Mr. Prime Minister, that the United States views these reports, if true, with deep concern. Any such decision by the Government of Israel would seriously undermine the urgent efforts being made by the United Nations to restore peace in the Middle East, and could not but bring about the condemnation of Israel as a violator of the principles as well as the directives of the United Nations.”

He added a “polite” threat at the bottom of the letter: “I need not assure you of the deep interest which the United States has in your country, nor recall the various elements of our policy of support to Israel in so many ways. It is in this context that I urge you to comply with the resolutions of the United Nations General Assembly dealing with the current crisis and to make your decision known immediately. It would be a matter of the greatest regret to all my countrymen if Israeli policy on a matter of such grave concern to the world should in any way impair the friendly cooperation between our two countries.”

A different kind of ‘Southern strategy’

Some of Eisenhower’s advisers worried in the lead-up to the election that his insistence on an Israeli withdrawal and support for resolutions that condemned Israel would cost him politically. Nixon didn’t share that concern, but when the president suggested in a private conversation that he could use force to stop Israel, his son John asked, “Won’t you lose the election?”

Eisenhower, according to a 2012 biography by historian Evan Thomas, couldn’t resist the comeback and told his son that he might actually “pick up a Southern state or two” if he stood up to Israel.

The 34th president, in other words, shared his vice president’s assessment that a confrontation with Israel wouldn’t harm him and could even serve him politically if he highlighted the fact that he kept “American boys” out of harm’s way.

In public, the president focused on an argument that America could not condone an attack by one sovereign nation against another. “We cannot – in the world, any more than in our own nation – subscribe to one law for the weak, another law for the strong,” he said in a speech on the eve of the election. “There are some firm principles that cannot bend – they can only break. And we shall not break ours.”

In private correspondences such as a letter to his friend Edward “Swede” Hazlet, Eisenhower went much further, accusing Ben-Gurion of timing the invasion one week before the election out of a false belief that the president would fear “the Jewish vote.”

“We realized that he might think he could take advantage of this country because of the approaching election and because of the importance that so many politicians in the past have attached to our Jewish vote,” Eisenhower wrote.

In a line that today would get any politician denounced as an antisemite, he added: “I gave strict orders to the State Department that they should inform Israel that we would handle our affairs exactly as though we didn’t have a Jew in America. The welfare and best interests of our own country were to be the sole criteria on which we operated.”

Hitchcock says that judging Eisenhower’s approach to Israel only through the prism of Suez would be a mistake, because the 34th president had “emotional sympathy” for the Jewish state and expressed support for Israel’s right to defend itself – but not at all costs. He added that Eisenhower felt betrayed by the Israeli-French-British maneuver. “It was completely crazy for them to do it, and even more crazy that the Americans were fooled,” he said.

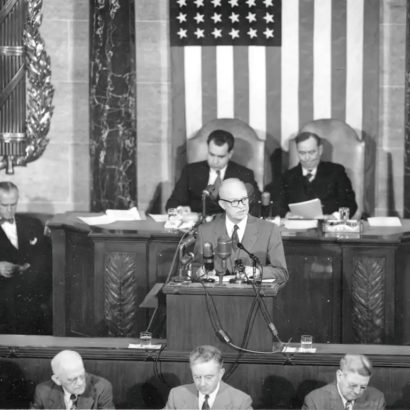

It took Eisenhower five more months after he easily won reelection to see Israel withdraw all its troops from Sinai, in return for a commitment to keep the Straits of Tiran open to Israel. In February 1957, while he was still busy pressuring Israel to make this move, Eisenhower met with congressional leaders in the White House to try to win their support for his policy.

LBJ supports Israel

The Senate majority leader at the time, Texas Democrat Lyndon Johnson, told Eisenhower he opposed the pressure being put on Israel.

“American politics on Israel were very different back then,” Kurtzer says. “It’s not a coincidence that the toughest moments Israel experienced in its early relationship with the U.S., whether it’s Eisenhower’s pressure in 1956 or Ford’s reassessment in 1975, came under Republican presidents.”

Johnson, for his part, would face his own moment of truth on Israel in 1967 when the country, by then a much closer ally of the United States, conquered even larger swaths of territory in the Six-Day War. Instead of pressuring Israel to withdraw, as Eisenhower did, Johnson accepted the “land for peace” formula that gave Israel the ability to keep the territories and negotiate with the Arab countries from a stronger position.

The impact of that decision is evident on the ground to this day.

Amir Tibon is the assignments editor and U.S. news editor for Haaretz

- RELATED:

- When George Bush, Sr. took on the Israel lobby, and paid for it

- Ike Forces Israel to End Occupation After Sinai Crisis

- Richard Nixon Twice Had Mideast Peace in His Grasp

- Half a Century Ago, It Was Washington Restraining France

- Richard Nixon Twice Had Mideast Peace in His Grasp

- Warriors at Suez

- The Lavon Affair: When Israel Firebombed U.S. Installations

- The Israel Lobby – John Mearsheimer & Stephen Walt

- Against Our Better Judgment: The Hidden History of How the U.S. Was Used to Create Israel

VIDEOS: