By Philip Weiss: “Israel’s dependence on lobby’s pressure will cause hostility to U.S. Jews, Nathan Glazer warned in 1976,” published in Mondoweiss February 24, 2017

[Boldface added]

Israel is becoming more and more isolated in the world, so it depends on one friend, the United States. But supporting Israel is not in America’s interests. In fact, Israel is a strategic liability for the U.S. That makes American Jewish influence the ultimate pillar of Israel’s survival. And that pressure comes at a considerable cost: American Jews will inevitably be exposed to hostility from non-Jews. Therefore, American Jews must press Israel for a declaration in exchange for wielding our influence: Israel will return to the 1967 lines in return for Arab recognition.

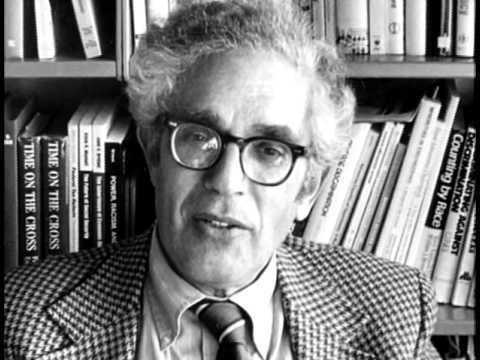

That’s a blunt and realistic assessment of the role, and risks, of the Israel lobby, right? And here is the amazing thing about the argument: the eminent Jewish scholar Nathan Glazer made it more than 40 years ago. The Harvard sociologist most famous for co-authorship of Beyond the Melting Pot, Glazer stated these ideas in very much those words in an essay in a dissident Jewish publication in 1976.

I lately came across Glazer’s essay, titled “American Jews and Israel: The Last Support,” in the New York Public Library. I typed it up. You can read the bulk of the essay below, followed by my commentary.

First the context. A crisis came for Jewish supporters of Israel in 1973, after the U.S. was compelled to airlift arms to Israel during the Yom Kippur War. On the right, Norman Podhoretz and Irving Kristol argued that American Jews should abandon the Democratic Party because it was dovish, and Israel depended on a hawkish American foreign policy. But on the left, the dissident group Breira was born, opposed to Israel’s militarism and occupation.

Though Nathan Glazer was a New York boy who’d been part of the famous socialist cell at the City College of New York, he has always been a free-thinker (see James Traub’s profile); and he thought that Israel needed to make peace. Breira only lasted a few years, before the Jewish establishment crushed it. But Glazer wrote his piece for the Breira publication, Interchange, in November 1976, when he was 54.

“American Jews and Israel: the last support,” by Nathan Glazer (with elisions marked by …)

History has so arranged matters that the Jews of Israel and the Jews of the United States are more closely linked and more desperately linked than they ever thought possible. According to the theories of Zionism, and until some time after the state of Israel was created, it was believed that Israel would serve as a cultural center for world Jewry, would revitalize Jewish education, culture, and religion in the diaspora, and –in the more political formulations of Zionism—would serve as a refuge for Jews and a supporter of Jewish interests in the world. It was expected that the Jews of the United States and other countries of the Diaspora would provide financial support for the upbuilding of Israel. In measure, things have worked out as expected. What was not expected, was that events would so develop that the United States would end up the last support for Israel, and that American Jews would thereby become crucial for the Jews of Israel.

What has brought this situation to pass is the progressive isolation of the State of Israel in the world. We must look back twenty five years to realize how far Israel has fallen in world support. At its birth, both superpowers, the United States and USSR, supported it. Most of the countries of the world agreed it should come into existence, should be legitimate as a state, should be a member of the United Nations. [Nathan may not have realized that the UN vote was accomplished through bribes and threats to members of the General Assembly. See Alison Weir’s book.]

All this is past. The cluster of the democracies in the world maintain relations with Israel and will speak for it on occasion in international forums. A scattering of other nations—principally in Latin America—maintain relations. But only one nation will on occasion speak forcefully for Israel. More significantly, only one nation will supply Israel with sophisticated arms, and can be depended on to resupply it in case of another war.

There are various explanations which are advanced for the consistent American support for Israel. What makes the issue murky is to define the set of influences that, in a multi-ethnic democracy that happens to be a world power and the leader of an alliance of democracies, play on the making of foreign policy decisions. While the question of who is in the command position is not unimportant, it is only one factor in a set of influences. It is the complex of influences, this and how we interpret them, that leads to discrepancies in how we rate the role of American Jews in maintaining American policy on its present course.

One explanation that is often argued to explain American support for Israel is that it is in American interests, broadly conceived, to maintain America’s support for Israel. I doubt that is true. It is clearly not to the material interests of the U.S., which are so often thought by the Left to affect American foreign policy, to continue the strong support of Israel. The Arab market is much larger than the Israeli. American business has a substantial share of the market, but undoubtedly it would have a larger share were it not for the strong connection between the United States and Israel.

It is also strongly argued that American security interests dictate the Israeli tie. The argument is hard to understand. The basic posture in the Middle East is that the United States tries to resist and slow the advance of Soviet influence in that area. It has two allies in this endeavor—Iran and Saudi Arabia—and is developing influence in Egypt. It is not inconceivable that the ruler of Iran, perhaps of Saudi Arabia, will be replaced by those who are more sympathetic to Russia. Such a change in Israeli is inconceivable. Israel is more constant in that respect, but it is also very small, provides no bases for the United States, limits the degree to which Middle East allies will adhere to us, produces constant hostility in our relations to states running from Algeria to Iraq.

American military men have often been pro-Israel because it is so effective militarily. In this respect, it can play a role in various strategic considerations. But when one considers the larger strategic picture, one suspects the commitment to Israel must be seen as an overall liability.

If it is not American material interests, not strategic interests, what then dictates the tie to Israel? Two things, one more tenuous, the other rather concrete. The more tenuous basis of the tie is the basic commitment of many Americans and American foreign policy to democracy, or, if you will, their opposition to Communism. This commitment has been the central pillar of American postwar foreign policy, and Israel has been the beneficiary.

At the present moment, we are engaged in the United States in a confused and serious struggle in which this American commitment to democracy is being undermined by analyses—generally from the liberal and left part of the political spectrum—which assert that concern for democracy has played no role in American foreign policy. Secondly, it is being undermined by the opposite argument that democracy should play no role in American foreign policy. After South Vietnam the abhorrence of any activist and interventionist foreign and military policy is understandable. It is not popular with new men in politics who have no recollection of the forging of the great postwar measures and alliances to restrain Communism and protect democracy. The fact is that Communism increasingly fails to arouse a moral reaction; those who take a moral view of it are seen as troublesome and troublemakers […]

All I am saying is that one central feature of this policy, opposition to Communism in its aspect as a denial of freedom and liberty, is now under attack, and it is just this feature of American foreign policy that should not be abandoned […] If this central feature is given up, then one reason for American support of Israel would disappear.

The second major pillar of American support for Israel seems firmer. It is American Jews. History has so arranged things that it is the only Jewish community that basically counts for the defense of Israel. American Jews are placed in a key position. But I believe this position is often misunderstood.

It is misunderstood in the United States where men as informed and important as the head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and a former vice president have ridiculously exaggerated notions of Jewish influence. It is misunderstood in Israel, where the power of American Jews is exaggerated, and the conditions which set a limit to the power are not understood.

Power is not something wielded in a vacuum. There are limits to the role any ethnic group may play in affecting American foreign policy. It should be recalled that we have gone to war twice against Germany despite the fact that Germans in the United States are four or five times as numerous as Jews, and we have gone to war against Italy, even though there are more Italians in the United States than Jews. An American ethnic group is benignly allowed to exercise its influence in defense of the interests of its homeland only as long as these do not conflict with what are seen to be larger interests. American Jews have power only because their fellow citizens are friendly to their exercise of this power. [Or, more likely, because their fellow citizens don”t know what’s going on, through media distortion and omission.] They can become less friendly to this exercise. They can indeed become hostile to it.

Thus, American Jews can raise considerable sums of money for Israel, on the basis of tax exemption for charity, though this money, used to absorb refugees, and for health and welfare services, aids at least in part to permit Israel to use other funds for arms. American Jews unabashedly lobby for pro-Israel measures with Congress, and make it politically uncomfortable to be against Israel and even take an “evenhanded” position. The political figure who does will be subject to much pressure and name-calling, some of it quite unfair. But as I have said, power must be seen in context. The context has been that it is safe for American Jews to do what they do. Political leaders have not resented the pressure much because it has not cost them much to support Israel. There is after all no substantial countervailing power. Insofar as Americans have opinions, they overwhelmingly support Israel.

Thus, I believe that those visiting Israelis who go away from Congresspeople convinced that they have nothing to fear and that American Jews need only keep up the pressure are wrong. There are three factors which are undermining American popular support for Israel and are increasing its costliness. First is that it has become costly financially. Until the 1973 war, Israel needed no substantial military credits or grants from the United States. Its own resources sufficed, along with overseas aid from Jews [which was massive]. Since then, first the replacement of arms destroyed in that war, and then the escalation of the arms race against infinitely more wealthy opponents have required heavy grants and credits, over $2 billion a year. This is an enormous sum to go to one small country, when it is realized that foreign aid of all kinds is unpopular in the U.S., and that this amount is almost half of all that the U.S budgets for foreign aid. This has already had political consequences. Congresspeople—some—have begun to question it, newspapers have begun to question it. Some Congresspeople have resisted appropriating these sums. Jewish organizations have tried to increase pressure on them, which has aroused their hostility of the lobby for Israel.

The second factor which is undermining American popular support for Israel is the shift in the way in which the American mass media –perhaps we should say the shift in the underlying realities of the situation. But let us separate image and reality for a moment. The image until 1973 was that Israel was ready to negotiate and talk with the Arabs, but the Arabs are intransigent and would not talk to Israel. This view has been reversed. Sadat appears – and is presented as moderate. All he wants back is his territories. Israelis are presented as intransigent and obdurate. One certainly finds sympathy for King Hussein. One may even find sympathy for Syria. All they want back is their territories. The Palestinian refugees have always had sympathy. They have much more now. One cannot underestimate the effect of front-page maps in the New York Times—there have been two recently—showing what looks like a dense mass of Jewish settlement in occupied Arab territory, or the influence of newspaper and television coverage of disorders on the West Bank. The images are reminiscent of Southern state troopers beating blacks – well-equipped soldiers grabbing young boys and girls. I do not suggest there is any intent in this. It is the nature of the media to focus in on the moment of violence when the soldiers grab the civilian, not the lengthly [sic] preceding period of taunts and rock-throwing.

The third element undermining American popular support is the same element that in the end may undermine American diplomatic and military support—the Arabs are strong, they are numerous, they are wealthy, they are clearly here to stay, while Israel… well, it requires endless effort to stay in the same place. People get tired.

If the present situation continues, popular support for Israel will weaken. Jewish pressure then on American policy becomes more costly—to Jews. Even now, of course, this pressure is not costless. A favor given in one area means one can deny a favor in another.

But what if there was a different Israeli policy? Would such a change reduce the developing pressures on American Jews from their countrymen to limit their uncategorical support? Could American Jews support a different policy more effectively, and with less threat to their position?

I fear that by asking these questions I will be interpreted as saying that because American Jews may find their position uncomfortable they should moderate their support for Israel, and press Israel against its better judgment, to undertake policies that may increase the risk of another holocaust. This is not what I am saying at all. The danger to which Israel is exposed pales any possible discomfort for American Jews. But that is my position, and neither other Americans nor American Jews will see it that way. Despite the fact that Jews have had it very good in the United States, there is among them an everpresent and underlying concern, sometimes fear, that things will change. This is a reality that must be taken into account. Israelis having fought four wars and living under a terrible siege, may have a legitimate disdain for whatever concern American Jews have for their condition, but they cannot ignore it in their calculations.

Is there a policy that might make it easier for American Jews to continue their unstinting support for Israel, and for the U.S. to accept their arguments? Can we find such a policy that does not increase the danger in which Israel lives, a danger such that one defeat risks annihilation? The argument is often made that “we cannot worry about public relations; since our lives are in danger, we must do whatever protects our security, and cannot risk this for good will.” The situation in the U.S., however, cannot be met by such an argument from the Israelis because the good will in question is not a fringe benefit that one can dispense with: it is the key element in Israeli defense, for without it, American military arms will flow more slowly or will be delayed in an emergency. Israel needs American good will as much as it needs American arms. The fact that a different policy may increase danger in one respect must be balanced by the fact that it makes possible the continuation of defense in another.

I—and others, in Israel, and out—believe there is such a policy that fulfills all these conditions. It is a policy which I suspect most American opinion—perhaps most American Jewish opinion—thought was Israeli policy after the 1967 war, but which in recent years, it has become clear, is less and less Israel’s policy. The policy I have in mind is for Israel to say and mean that all the gains of the 1967 war will be given up for real peace—recognition, open frontiers, trade, guarantees for peace, and for Israel to say it will talk to any parties to the dispute face to face to achieve such a settlement. There are many arguments to be made in favor of such a policy: while most of the world seemed to accept the 1967 frontiers as legitimate (they had, after all, lasted almost 20 years), none of it accepts the present frontiers as permanent; that some of the parties on the Arab side and in time, perhaps most, might be willing to accept the 1967 borders as permanent, but none will ever accept the present frontiers as permanent, or any frontiers that include part of the 1967 conquests; and that Israel needs most of all in the world, peace based on legitimacy.

While no one can dismiss the argument that the Arabs will never accept anything but the destruction of Israel, the policy proposed here has a safeguard. The return to the 1967 borders is based on actions that the Arab states must take, actions that have been enormously difficult for them to take in the past, but which if they do take now would signify a willingness to say to their people that they must begin to contemplate living with Israel in peace. We should not underestimate the significance of such words. Words principally will be required from the Arab states at this point but what is required in exchange for all the territories are infinitely important words—recognition, acceptance, regular trade and tourist relations, the ending of the boycott, and some of these involve actions as well as words.

I know the difficulties Israel faces as a democratic state in adopting such a policy, but if this policy is the means by which the support from the U.S. is continued to be assured and peace may ultimately be glimpsed, too, then Israeli leaders must be bold enough to propose it and argue for it with their people. It is playacting for Israel to say in the present juncture we will keep this, and we will need that, and we are not really sure what we can give back. The situation has never existed in which such options were open to Israel: the Arabs would never accept them and no nation in the world would support Israel in changing the 1967 borders.

To conclude: Israeli security now depends almost entirely on American support, political and military. That support is crucially, though not entirely, dependent on the pressure of American Jews in support of Israel. A policy which American public opinion cannot accept as just is not a policy that the U.S. can continue to uphold; and the efforts of American Jews to uphold American support for it will then also weaken. The present course is clearly dangerous to Israel’s survival; the alternative offers some hope, first and at the least, for an important public relations advantage today—not unimportant in a democracy—but also—and this I admit is more doubtful—for an ultimate settlement in the future.

A few comments:

I don’t think there is a more frank and candid description of the role of the Israel lobby to be found at that stage of its existence. Notice there is no bullshit about Christian Zionism being Israel’s pillar, or George Washington and Abraham Lincoln wanting the return to Jerusalem, as Zionism’s defenders claim today, when there is a whole propaganda industry dedicated to denying what Glazer states baldly: Israel depends on American Jews, because it’s not in American material or strategic interests to support it.

Just what Nathan Glazer said in 1976, Stephen Walt and John Mearsheimer, two non-Jewish scholars, said 30 years later in the London Review of Books. They got smeared as anti-Semites for telling the truth about the pro-Israel Jewish community’s influence and the neoconservative impetus for the Iraq war. Though they were read in the highest offices of government, and ignited the Israel lobby debate, which continues at the margins of the mainstream to this day– with a yearly conference on the matter coming next month in Washington. [The first such conference came in 2014]

[Before the Mearsheimer-Walt book, Paul Findley exposed the pervasive power of the Israel lobby in his must-read book, They Dare to Speak Out.]

Notice what Glazer got wrong. He said that supporting Israel as it grew progressively isolated was so much against American interests that Jewish pressure would end up undermining the Jewish position in the United States. Not so! American Jewish support only got stronger for 40 years, Breira was pushed off stage (in part through the offices of young ideologue Wolf I. Blitzer), and Israel kept erasing the 1967 lines and getting more and more isolated. But American stayed at its side. Glazer said Israeli Jews were wrong to believe that the U.S. can be pushed around; but maybe they weren’t. That is precisely what Benjamin Netanyahu said in his famous hot-mic moment in 2002: The U.S. can be easily moved. And the war against radical Islam is only cementing the bond between the countries’ leaderships.

Why was Glazer so wrong? As I have insisted in all discussions of the Israel lobby, the lobby’s success cannot be disentwined from the rise of Jews into the establishment. Glazer was writing at a time when Alan Dershowitz had angrily threatened to leave Harvard Law School unless a Jew was finally named dean. Glazer and Dershowitz could not have imagined the degree of Jewish inclusion that was to follow the 70s, with Jews at the heads of global industries from finance to education to Hollywood, and in leading positions in government and media, including three Jews on the Supreme Court. The US establishment came to rely on the Jewish presence; and part of the deal was deference to the Israel lobby, notably a multitude of neocons and Zionists in policy-making positions from Clinton to Bush to Obama.

That deal may well be unraveling as we speak. So Nathan Glazer’s words are prescient after all.

Let’s revisit Glazer’s warning about anti-Semitic reaction. In 2014, Bruce Shipman, the Episcopalian chaplain at Yale, lost his job for a short letter to the New York Times saying that Israel’s onslaught on Gaza, which had killed 2200 Palestinians, was fueling anti-Semitism around the world; and the best antidote was for “Israel’s patrons abroad to press the government of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu for final-status resolution to the Palestinian question.” Last week the New York Times ran another letter with a very similar message. Roderick Balfour, a descendant of Arthur Balfour, the British foreign secretary who penned the Balfour Declaration 100 years ago, said that Israel’s inability to respect Palestinian rights “coupled with the expansion into Arab territory of the Jewish settlements, are major factors in growing anti-Semitism around the world.”

Glazer said the same thing: There will be “hostility” toward American Jews unless they put pressure on Israel to announce that it will end the occupation. The great pity is that American Jews have not heeded his advice for 40 years; and the occupation is more solid than ever; and no one who studies the conflict can imagine a peaceful resolution.