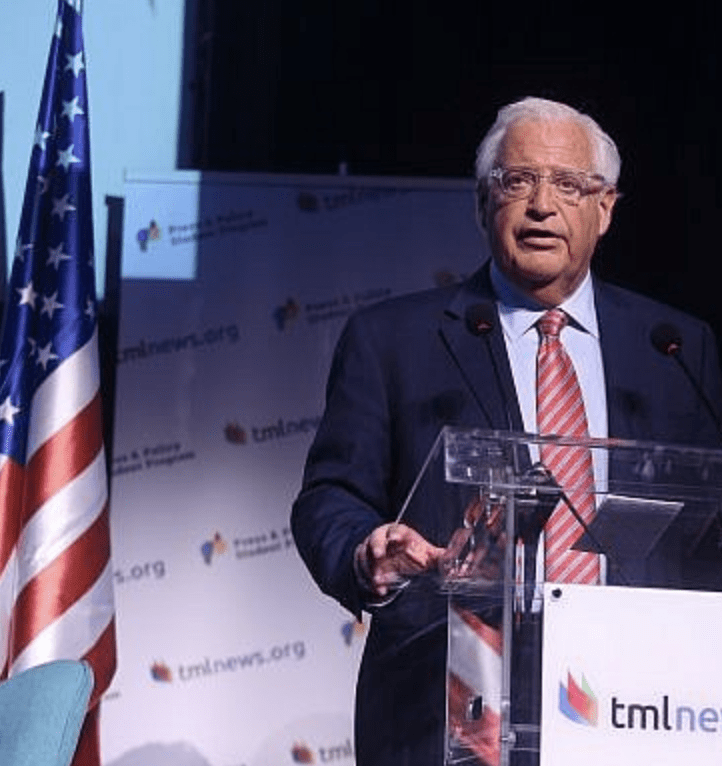

People who have interacted with David Friedman say his diplomatic inexperience shows. But his defenders say he’s injected a dose of reality into the 70-year-old Israeli-Palestinian conflict. | Menahem Kahana/AFP/Getty Images

Donald Trump’s envoy to Jerusalem rejects criticism of Israel’s policies and resisted efforts to apply Leahy Law – limitations on funding to human rights violators.

By Nahal Toosi, Politico

Last October, the U.S. ambassador to Israel, David Friedman, emailed State Department colleagues with a firm message: Don’t second-guess the Israeli military.

State Department officials had recently asked U.S. embassies in the Middle East to more carefully examine American military assistance to governments in the region, including Israel. The goal was to ensure the department wasn’t violating a law barring U.S. security aid to foreign military units that commit serious human rights abuses. Some Democrats in Congress have questioned whether Israel’s military — which receives an annual $3.1 billion from the United States, more than any other nation — might be guilty of human rights infractions against Palestinians.

Friedman dismissed the possibility. In the email to colleagues, he rejected the idea that his embassy needed to enhance its scrutiny of military aid, saying he did “not believe we should extend the new [guidelines] to Israel at this time.”

“Israel is a democracy whose army does not engage in gross violations of human rights,” Friedman wrote, adding that Israel “has a robust system of investigation and prosecution in the rare circumstance where misconduct occurs.” Besides, he added, “it would be against [U.S.] national interests” to take a step that could limit Israel’s access to military equipment – “especially in a time of war.”

Several months later, Israeli forces are under harsh international scrutiny for killing scores of Palestinians during border protests in the Gaza Strip. Friedman has rejected charges that Israel used excessive force; Israeli officials insist they acted with restraint against violent provocations.

Friedman’s email, part of a chain shown to POLITICO by a former State Department official familiar with the issue, offers a glimpse into the worldview of one of President Donald Trump’s most influential — and controversial — ambassadors. Along with other anecdotes about his tenure, it suggests that the blunt-spoken former Trump bankruptcy lawyer sees his host country, which he has long considered a second home, as virtually beyond reproach. It also underscores the stark pro-Israel tone of Trump’s foreign policy as the president works to devise a proposal for a long-elusive Middle East peace.

It has been a busy spring for the 59-year-old Friedman. Last month, he attended the opening ceremony for the first U.S. Embassy in Jerusalem, opened by Trump despite furious criticism from Palestinian officials. Sources say Friedman played a key role in persuading Trump to recognize Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and relocate America’s embassy there from Tel Aviv.

Friedman was in Washington this past week for White House meetings about an Israeli-Palestinian peace plan that Trump’s team may unveil this summer, and he is expected to be joined in Israel next week by Trump’s son-in-law and adviser, Jared Kushner, and another top Trump aide, Jason Greenblatt, for talks with Israeli officials.

To supporters, Friedman is a valuable emissary to a welcoming Israeli government. “Ambassador Friedman has done a terrific job and is widely respected across the political spectrum in Israel,” said Ron Dermer, Israel’s ambassador to the United States. “Israel’s leaders appreciate his close relationship with President Trump and know that he speaks to and for the president in a way that perhaps none of his predecessors did.”

“He’s not a career diplomat. He doesn’t fall into the trap of diplomatic speak,” said Matt Brooks, executive director of the Republican Jewish Coalition. “The only thing you can accuse David Friedman of is speaking truthfully. If that offends people, so be it.”

But critics say Friedman champions a right-wing agenda that doesn’t reflect broad opinion in either the United States or Israel itself. And they warn that his hard line toward the Palestinians and reflexive defense of Israel’s security forces is making a peace agreement harder than ever to achieve.

“We could never really imagine that Mr. Friedman could play any positive role,” said Saeb Erekat, chief negotiator for the Palestinian Authority.

A “direct line” to Trump

State Department officials who work on Israeli-Palestinian issues declined to comment for this story. But POLITICO spoke to nearly a dozen former State Department officials, congressional staffers and human rights activists, among others, for a sense of how Friedman operates.

Friedman grew up in an Orthodox Jewish community in Long Island, earned a law degree from New York University and became a bankruptcy law expert who represented Trump when his Atlantic City casinos went under. He has been a fervent Israel backer for decades, and has raised money to support Israeli settlers in territories Palestinians claim for a future state.

Friedman started representing Trump in the early 2000s, including handling cases involving the future president’s troubled Atlantic City casinos. Friedman had no prior diplomatic experience when Trump tapped him to become ambassador to one of America’s closest allies. His close relationship with Trump has given him unusual power — as well as autonomy, allowing him to sidestep traditional diplomatic channels, of which he is suspicious, and communicate directly with Kushner and the president.

“Based on what he wrote before he was in government, he seemed to view the State Department as sort of the enemy because he deemed its diplomats as insufficiently supportive of Israel,” a former senior State Department official said. “But he also has no need for it. He has a direct line to the president of the United States.”

People who have interacted with Friedman say his diplomatic inexperience shows. Shortly before his official arrival in Israel last year, State Department officials briefed Friedman about the humanitarian crisis in Gaza, a Palestinian territory under an Israeli blockade and controlled by the militant group Hamas.

According to the former State Department official familiar with the issue, at one point in the briefing Friedman said: “I don’t understand. The people in Gaza – they’re basically Egyptians. Why doesn’t Egypt take them back?” A briefer informed him that most of Gaza’s residents were refugees or descended from refugees who had lived in what is now Israel. (Friedman denied making the comment to The New Yorker, which recently reported the same incident. A State Department spokesperson told POLITICO the anecdote is false.)

Friedman has also questioned U.S. intelligence assessments about Palestinian leaders’ activities. In one instance, he said that Israeli officials had told him that U.S. intelligence officials knew that Palestinian leaders had asked the International Criminal Court to investigate Israel. Under U.S. law, that could mean the Palestinians would have to close their office in Washington. U.S. officials told Friedman that American intelligence had not detected any relevant Palestinian contact with the ICC. In an email, Friedman objected to that conclusion— puzzling officials who wondered why he was taking the word of the Israelis over the Americans, according to the former State Department official.

A State Department spokesperson denied this incident. The department also denied POLITICO’s request to interview Friedman.

Palestinian leader Mahmoud Abbas in September gave a speech to the United Nations calling on the ICC to investigate Israel, but after much debate the Palestinians were allowed to keep their office open.

Friedman also has insisted that the State Department stop using the term “occupied territories” to refer to the West Bank and Gaza, an approach the department adopted in its latest human rights report.

After Friedman found himself on the winning side of the debate about whether to relocate the U.S. embassy to Jerusalem — his ostensible boss, former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, had opposed the move — he managed a second win. Tillerson insisted that moving the embassy could take several years. But Friedman successfully pushed Trump to designate an existing U.S. facility in Jerusalem as the embassy, former State Department officials said.

The dedication took place in mid-May; a permanent site is expected to take up to a decade to build.

‘Keep your mouths shut’

The May 14 embassy dedication ceremony, attended by Kushner and his wife, Ivanka, the president’s daughter, was a heady day for Friedman, but it was marred by some of the worst violence between Israel and the Palestinians in several years.

A series of protests by Palestinians along the Gaza border crescendoed that day — with the encouragement of Hamas. Israeli security forces killed more than 60 protesters as U.S. and Israeli officials celebrated at the new embassy. Since late March, Israeli forces have killed more than 100 protesters in Gaza, while wounding thousands more, according to Human Rights Watch.

In the weeks afterward, as rights groups denounced what they called a disproportionate show of force, Friedman lashed out at reporters questioning Israel’s response, telling them they failed to understand the issue and to “keep your mouths shut until you figure it out.”

The burst of violence came several months after Friedman dismissed the need to enhance vetting of U.S. military aid to Israel.

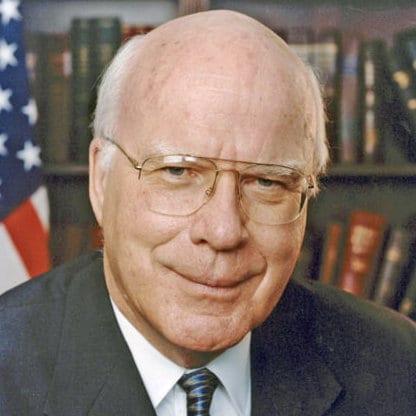

The vetting issue involves U.S. laws authored by Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) that are designed to ensure that U.S. weapons, training, funding and other aid does not support foreign military units found to have committed “gross violations of human rights,” which can include torture, rape and extrajudicial killings.

Activists have long complained that while the State Department applies careful screening to resources used to train foreign military units, other forms of aid, such as transferred equipment, are less closely vetted. The problem is that training is just a small slice of U.S. military aid to foreign countries. One recent State Department report listed the amount of money the U.S. spent on training Israeli soldiers as less than $2 million a year, next to nothing compared to the $3.1 billion America sends to Israel annually. Experts say such small amounts line up with what they’ve found in studying the Leahy laws.

Several lawyers, activists, former State officials and others reached by POLITICO could not recall a single instance of the U.S. withholding any sort of assistance from an Israeli unit for reasons related to human rights infractions. But Leahy and other Democrats in Congress have questioned whether the U.S. scrutiny has been sufficient, including in a 2016 letter to then-Secretary of State John Kerry.

The issue came to a head inside State last year after the department’s inspector general released a review of by the bureau overseeing the Middle East and determined that American embassies in the region were not sufficiently tracking whether the disbursement of U.S. military aid was meeting the Leahy laws’ requirements.

Middle Eastern nations receive a huge chunk of U.S. foreign military assistance, most of it going to Israel and Egypt. Israel will soon be receiving hundreds of millions of dollars more each year under a 10-year agreement reached under former President Barack Obama.

The internal State Department review noted that the Government Accountability Office had found similar problems in a previous report focused on the U.S. Embassy in Egypt. The inspector general recommended that all the embassies in the region implement better vetting procedures to address “potential weaknesses.”

In his email, Friedman insisted that the existing vetting process in Israel was fine. “My understanding is that nothing is broken that requires a repair,” he wrote.

Friedman also questioned the very basis of the new assessments, which he cited as the GAO report on the U.S. mission in Egypt, instead of the broader inspector general’s report.

“Post disagrees with the assessment that the Department should proactively address Israel based on GAO criticism of procedures in Egypt,” Friedman wrote. “We cannot and should not assume that GAO intended to apply the same criticism to Tel Aviv. If and when they do criticize Embassy Tel Aviv for these issues, it would be more appropriate to react at that time.”

The former State Department official familiar with the issue said Friedman persevered and that no new guidelines applying to Israel were implemented. The State Department did not answer repeated questions about which embassies in the region adopted new vetting procedures and which ones did not.

In a statement to POLITICO, Leahy said the laws he authored “do not distinguish between democracies, autocracies or other governments, nor do they depend on whether a country is in the midst of an armed conflict or at peace.”

“What matters is whether a unit of a foreign security force has committed a heinous crime, like shooting an unarmed civilian or raping a prisoner, and whether the foreign government is bringing the responsible members of the unit to justice,” Leahy added. “The alternative is to turn a blind eye to atrocities committed by foreign units trained and equipped by the United States.”

This week, Human Rights Watch declared that the killings of Palestinians in Gaza by Israeli security forces “may amount to war crimes.” Among the dead was a young Palestinian medic. Rights activists fear that no Israeli troops would face discipline, pointing to reports which suggest that rarely happens.

Israeli officials vehemently defend their troops and justice system. They note that Palestinian protesters have thrown explosive devices, rocks and other items at soldiers. Hamas has also said many of those killed were its members.

While it did not respond to many of POLITICO’s questions, the State Department insisted nothing was unusual about its application of the Leahy laws to Israel.

“The State Department continues to apply the Leahy Law across the board, including in Israel, as it has for years,” a spokesman said in a written statement. (The two laws are often spoken of as one.) “There has been no change to our procedures. Ambassador Friedman has not instructed anyone to ignore the Leahy Law, nor has he asked for any changes be made to how the law is implemented.”

Partisan ideologue or “nuanced” diplomat?

Friedman’s defenders say he is aware of the complexity of the issues facing him, but that he’s injected a dose of reality into the 70-year-old Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

They argue that some of his most inflammatory remarks have been taken out of context — including his recent claim to an Israeli newspaper that there is “no question Republicans support Israel more than Democrats.” In remarks before he became ambassador, Friedman also likened liberal American Jewish activists to so-called kapos, or Jews who assisted Nazi concentration camp guards. (He later apologized.)

“If you look at the serious speeches that he’s delivered, at different conferences or different events, they are very nuanced,” said Nathan Diament, executive director for public policy with the Orthodox Union, an umbrella group of Orthodox Jewish congregations. “To the degree that some critics want to portray him as a one-dimensional right-wing ideologue, that’s not reflected in how he’s addressed policy issues as ambassador.”

Friedman has backed efforts to boost the Palestinian economy, Diament noted. But Palestinian leaders say Friedman has done little to earn their trust. Erekat, the Palestinian Authority negotiator, said that in a meeting with Friedman, the ambassador “tried to convince us that we could not do anything regarding Israel’s power.”

The Trump administration plans to press forth with its peace proposal with or without Palestinian participation, however. Kushner and Greenblatt will visit Saudi Arabia and Egypt as well as Israel next week to discuss their peace proposal.

According to a White House National Security Council spokesman, the American officials “are not going to meet Palestinian officials in Ramallah because the Palestinian leadership made it clear they don’t want to meet the peace team.”

The spokesman added, however, that “if the Palestinian leadership wants to meet, Kushner and Greenblatt are ready to meet.”

Related Reading:

Leahy Law would cut aid to Israel, but no one wants to enforce it