“You’re no longer alleviating humanitarian need – you’re becoming a cog in the machine of systemic oppression.”

By Riley Sparks, Reposted from The New Humanitarian, February 11, 2026

At the end of February, 37 aid organizations in the Gaza Strip – including nearly all established non-UN aid groups there – face a ban for refusing to comply with Israel’s new registration law. In their place, Israel has approved two dozen groups that have agreed to the requirements, which critics say aim to muzzle advocacy and manipulate the aid response to serve Israel’s political and military goals.

At a glance: Israel’s preferred aid groups

The New Humanitarian conducted a months-long investigation into NGOs that are scaling up their operations in Gaza as Israeli authorities push out established aid groups. Here’s what we found:

- All of the main groups now being allowed to scale up have downplayed or avoided talking about Israel’s military conduct in Gaza, which has been termed a genocide by a UN commission of inquiry and numerous right groups, international legal experts, and genocide scholars

- Senior staff from several of the organizations were photographed at militarized food distribution sites run by the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation, where over 1,100 Palestinians were killed by Israeli forces and US security contractors last year

- One of the organizations worked as a partner with the GHF and sent staff to its sites

- At least one NGO that shares leadership and staff with a group positioning itself to replace established actors has donated equipment to the Israeli military, including to units accused of war crimes, and to illegal Israeli settlements in the West Bank

- Several organizations are also working closely with Israeli authorities in parts of southwestern Syria occupied by Israel since late 2024

- Senior leadership from several of the organizations have repeated Israeli government talking points, including one who denied there was a famine in Gaza after the world’s foremost authority on hunger declared one was taking place last August

To investigate further, The New Humanitarian combed through publicly available information about the Israel-approved aid groups, spoke to senior leaders from several of them, and interviewed more than a dozen other aid workers and experts.

The investigation found that the new cohort of Israel-approved groups scaling up in Gaza can roughly be divided into two categories: those that appear well-intentioned but have chosen to barter silence for access, and others that seem more politically aligned with Israeli authorities.

All of the main groups now being favored by Israeli authorities have downplayed or avoided talking about Israeli conduct in Gaza, and senior officials from several of them have publicly supported Israel’s military campaign and repeated Israeli government talking points – including dismissing evidence of famine as “fake news”.

The world’s foremost authority on hunger, the IPC, declared a famine was taking place in parts of Gaza in August last year. The following month, an independent UN commission of inquiry determined that Israel had committed genocide in the enclave – a conclusion supported by numerous international human rights organizations, legal experts, and genocide scholars.

In comparison, those about to be banned include large groups that have traditionally seen humanitarian advocacy as an important part of their role, like Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), the Norwegian Refugee Council, Mercy Corps, Medical Aid for Palestinians, and Oxfam, as well as one of the longest-serving international NGOs in Gaza, the American Friends Service Committee – a Quaker aid agency working there since 1948.

At least one NGO that shares leadership and staff with a group positioning itself to replace these established actors has donated equipment to the Israeli military, including to units accused of war crimes. The group has also donated goods to illegal Israeli settlements. Several are also working in southwestern Syria in close coordination with Israel, whose military is digging in there for what may be a long-term occupation.

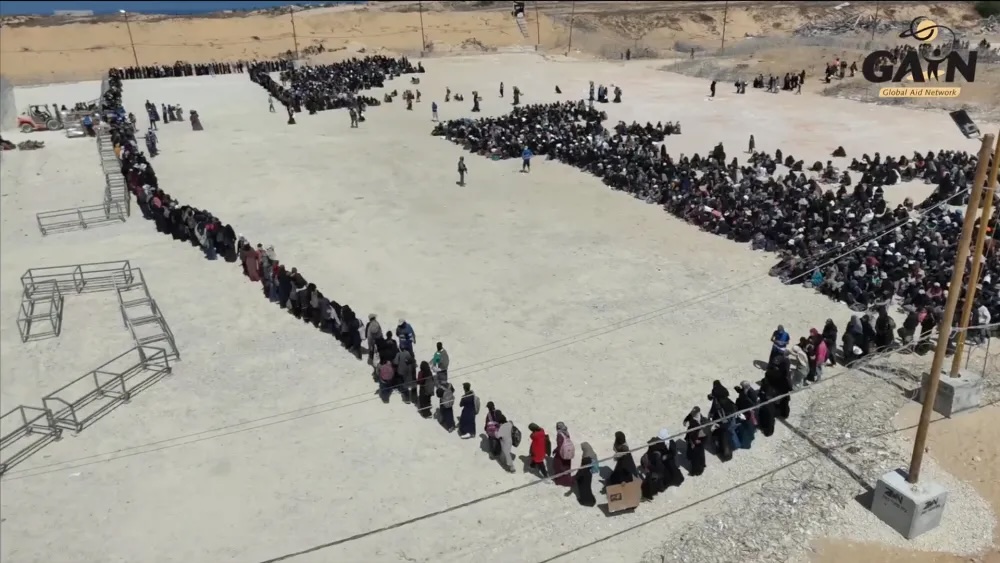

Senior members of several of the groups were also photographed handing out food at the militarized food distribution sites run by the US- and Israeli-backed Gaza Humanitarian Foundation (GHF) during the summer of 2025. Attacks by Israeli troops and American contractors at GHF distribution sites killed over 1,100 people and injured thousands of others between the end of May and early September 2025.

One group, Samaritan’s Purse, partnered with the GHF and sent staff to its sites. At least two others, Global Aid Network (GAiN) and Time of Freedom, later used the images of senior staff at the sites in their fundraising or communications.

In addition to these organizations, the list of approved NGOs includes a few large groups like World Central Kitchen, Catholic Relief Services, and ACTED, but many others have little or no humanitarian experience.

According to several aid workers, the preference being given to this new cohort of groups – while other aid actors are squeezed out – is part of a longstanding effort by Israeli authorities to establish a parallel aid system that they can more easily control both by exerting authority over existing NGOs and propping up new actors, and to sideline those more likely to speak out.

Israel is “re-engineering the space of humanitarian actors in Gaza”, explained one senior aid worker familiar with the situation, who asked to remain anonymous due to fears of retribution against their organization. “The ones that are going to be operating inside Gaza are new, small, politically convenient – and they’re not going to do anything independently without getting approval from the Israeli side.”

A more compliant system

From the beginning of the campaign in Gaza in October 2023, Israeli authorities have severely restricted the ability of aid groups to import supplies and operate.

Four months into the ceasefire that began in early October last year, which Israeli forces have continually violated, aid workers have made some progress in the face of continued obstruction, but the situation in Gaza remains catastrophic. Israel has allowed more aid in than during the famine-level era of mid-2025, but nowhere near the quantity stipulated by the ceasefire agreement. The Israeli military also recently recommended further cuts to aid deliveries, and UN data shows that the amount of cargo already appears to have decreased in January.

Authorities have also escalated their multi-front campaign against humanitarians. At the end of December, Israel announced its ban on NGOs that haven’t complied with the new registration law. In January, authorities demolished the Jerusalem headquarters of UNRWA, the UN’s agency for Palestine refugees, in violation of international law protecting UN premises. The Israeli parliament also moved to cut power and water to UNRWA facilities in occupied East Jerusalem and remove its diplomatic immunity, which is also guaranteed by international law.

Israeli authorities have cited the existence of the new cohort of registered organizations to support their claim that groups that haven’t complied with requirements can be banned without reducing aid delivery to Gaza – an assertion disputed by aid workers.

Meanwhile, the past conduct and statements of some of the registered organizations have raised significant questions about their political interests and partiality. This includes a cluster of interlinked groups that are members of the Helping Hand Global Forum (HHGF), an Israel-based umbrella organization for mostly evangelical Christian international charities working in Israel. HHGF is the international branch of Israel-based charity Helping Hand Coalition (HHC), which works in Israel and in illegal settlements in the occupied West Bank.

UN data show that two HHGF members – Poland-based Fundacja Czas Wolnosci, or Time of Freedom (TOF), and the German branch of GAiN, which is the international humanitarian arm of US evangelical group Cru, formerly Campus Crusade for Christ – have been authorized to bring at least 361 trucks into Gaza since the ceasefire in October 2025. Combined, that’s the fifth-highest total among groups tracked by the UN, behind four UN agencies and World Central Kitchen. Groups bringing in supplies outside the UN system are not tracked.

Donations to the Israeli military

Photos and public statements from GAiN, TOF, and HHGF suggest they work closely together on the Gaza response. GAiN is also a founding member of HHGF, and its officials sit on the HHC and HHGF boards. Israeli authorities recently registered a third member organization of HHGF, Poland-based Fundacja ESPA; it’s unclear if the group is present on the ground in Gaza.

GAiN has a logistics base and has operated a soup kitchen in Khan Younis, just west of the yellow line – the Israeli-drawn boundary cutting Gaza in half. Israeli forces are still deployed east of the line, which amounts to over 50% of Gaza’s territory, and regularly fire on Palestinians near the line, as well as elsewhere in Gaza.

GAiN, HHGF, and HHC did not agree to interviews with The New Humanitarian. A spokesperson for GAiN, and HHGF and HHC chair Andrzej Gasiorowski both responded in writing to a final request for comment sent before publication. TOF president Agata Witkowska agreed to an interview and then backed out; she and the GAiN spokesperson referred further questions to Gasiorowski.

GAiN provides aid only to families “known to the Israeli authorities”, the organization says. Gasiorowski confirmed that GAiN has delivered goods to both sides of the yellow line.

Almost no civilians live on the eastern side of the yellow line, and aid workers familiar with the situation in Gaza said the few Palestinians who remain there are mostly associated with Israeli-backed gangs or militias – including the Popular Forces (previously led by the now-dead Yasser Abu Shabab), which control the area around the Kerem Shalom crossing where almost all aid enters Gaza.

This gang was responsible for systematic violent looting of aid trucks throughout 2025, and has recently been accused of abusing and robbing Palestinians returning to Gaza through the Rafah border crossing, which reopened on 1 February.

In a statement, Gasiorowski wrote that GAiN “categorically rejects claims that it knowingly delivered aid to militias or armed groups”.

Although their first trucks were only delivered at the end of October 2025, GAiN and TOF have been in Gaza before: Photos and videos show senior members handing out GHF-branded food at a militarized distribution site in mid-2025. GAiN said they had visited the site while deciding whether the group would partner with GHF.

In an interview published in a German magazine in February 2026, GAiN founder and executive director Klaus Dewald, a senior figure in the organization’s Gaza response, said he had visited GHF sites while they were in operation and believed the media depiction of the hubs was inaccurate.

According to statements published by HHC, goods from GAiN and HHC have been donated to the Israeli military before and since October 2023. This includes non-lethal gear donated by HHC since October 2023 to the military’s Givati and Golani brigades and the Israeli border police. Both brigades have been accused of multiple war crimes, including the Golani brigade’s massacre of 15 Palestinian paramedics and rescue workers in Rafah in March 2025, and Givati’s role in razing schools in northern Gaza.

Other donations include tactical boots to commando units in 2025 – “ensuring our brave soldiers are prepared for any mission as they risk their lives to defend the Land of Israel”, HHC wrote – as well as uniforms in 2024 and a trailer for troops on the Lebanese border in December 2023.

Supplies from GAiN’s German and Polish chapters, including boots and clothes, have also been donated to the military for several years, including to soldiers returning from Gaza in 2024. The latter were handed over at a welcome-home celebration attended by HHC officials and Itamar Ben Gvir, the extremist Israeli minister of national security, who is now banned from the EU and who recently promoted the commander of a border police unit filmed executing surrendering Palestinians in the West Bank.

Gasiorowski initially said GAiN never donated to the Israeli military; when asked about some of these specific instances, he reiterated the denial and said GAiN’s role was limited to providing goods to local partners; he added that if HHC has said GAiN donations were provided to the Israeli military, questions should be directed to HHC, which he chairs.

GAiN spokesperson Lucas Wörpel wrote: “The distribution of GAiN relief supplies by our local partners is contractually regulated; HHC is not permitted to pass on our relief supplies to military personnel.”

The donations have happened at least since 2022, and were widely publicized by HHC; GAiN’s Dewald also sits on HHC’s board and is one of its founders.

HHC and HHGF senior staff include current and former Israeli military members and officers – including HHC executive director Luke Gasiorowski, a senior member of their response in Gaza, and one of those photographed at a GHF hub in 2025. An Israeli reservist, Gasiorowski, was mobilized during the Israeli offensive in Gaza in 2014 and again after Hamas’s October 2023 attacks, although The New Humanitarian could not confirm whether he was deployed in the enclave.

In a statement, Andrzej Gasiorowski, who is Luke’s father, wrote: “HHC and HHGF, and their affiliated entities, are not parties to the conflict and do not engage in, support, or coordinate any military activity.” He added: “Individuals who are mobilized in reserve or national service roles do not perform humanitarian functions during such periods.”

Gaza and beyond

HHGF is also one of at least two recently registered groups to have drawn up a scheme for camps for displaced Palestinians in Gaza – to be built in areas destroyed by Israeli forces. The plan, co-led by an Israeli real estate developer, includes modular container housing and a tourist “Riviera District”.

It’s unclear how this plan was developed, but ideas in the same vein have been frequently discussed by senior US officials, as well as by Israeli leaders who have envisioned forcing Palestinians into what former Israeli prime minister Ehud Olmert described as a “concentration camp”. Legal and human rights experts have said all of these ideas would likely involve a host of international law violations.

Several of these groups are also working outside Gaza in areas where Israeli authorities are trying to expand their control of territory.

Two have donated to illegal Israeli settlements in the West Bank: HHC provided “defence tools” – including cameras, surveillance systems, drones, and a night vision device – to a settlement north of the town of Birzeit, near Ramallah, in November 2025; HHC also delivered clothes and other items donated by GAiN, to Ma’ale Adumim, a large settlement near Jerusalem.

Andrzej Gasiorowski initially said GAiN had never donated goods to settlements; in a later statement, he wrote that, as with the goods it had donated to the Israeli military, GAiN had provided items to one of its “trusted partners” – HHC – which then donated them to settlements.

Many of the same groups are also working in coordination with Israeli authorities in southwestern Syria, where, since late 2024, Israel has seized an estimated 600 to 800 square kilometres, expanding an occupation that began with its 1967 capture and later illegal annexation of the Golan Heights.

Aiming to shore up its foothold in Syria, and as part of a broader effort to undermine the country’s new government, Israel is providing a local militia from the Druze community – an ethnoreligious minority group – with weapons, military gear, and money, as well as sending civilian equipment and coordinating with NGOs providing services in the area, including GAiN and TOF.

Photos and videos show senior members of GAiN, TOF, and HHGF dropping off goods in 2025 in parts of Syria now occupied by Israel, including the Druze community of Hader, where they brought mattresses donated to GAiN by German companies.

According to a social media post by Andrzej Gasiorowski, that mission was undertaken “at the request of COGAT”, the branch of the Israeli military responsible for coordinating Israeli government activity in the occupied Palestinian territories. Syria is not part of the occupied Palestinian territories.

“COGAT, as the authority responsible for civilian coordination in controlled border areas, identified opportunities for humanitarian access or conveyed civilian needs, and enabled secure passage or logistical clearance where required,” Andrzej Gasiorowski wrote. He said his post was not meant to imply “direction, control, or implementation by any military authority” of the work in Syria.

In a post shared by HHGF, GAiN said they aim to continue working with Israeli authorities in the region, including on plans for a hospital and other infrastructure.

Responding to The New Humanitarian’s questions, Gasiorowski, who represents GAiN, HHC, and HHGF, said that all three groups are “independent humanitarian and civil-society organizations and are not politically aligned with, directed by, or acting on behalf of any government or military authority”.

Two other groups now working in Gaza have also recently worked in Syria in coordination with Israeli officials: Natan, which works in Gaza with US-based NGOs Gaza Children’s Village and All Hands and Hearts; and Multifaith Alliance, which previously worked with Israeli forces in Syria beginning around 2016.

Despite GAiN’s close relationship with Israeli officials, it has still run into rocky territory: GAiN’s imports to Gaza have been blocked since early January, after what the organization said were attempts to smuggle goods on a truck without the knowledge of GAiN staff.

In response to The New Humanitarian’s questions about the smuggling allegations, Gasiorowski said GAiN was reviewing whether it would continue delivering to Gaza.

Responding more broadly, Gasiorowski added: “If public perception continues to draw conclusions that disregard facts, intent, and realities on the ground, it raises serious questions about the need and sustainability of our engagement in Gaza… perhaps it would be reasonable to just quit at this point our activities.”

TOF delivered its most recent shipment to Gaza on 25 January, according to UN data.

Echoing talking points or silence

As Israeli forces continue to target and kill Palestinian journalists and prevent their international colleagues from entering Gaza, humanitarians have been some of the only international witnesses able to communicate what is happening on the ground to global audiences. Silencing them is seen as a key goal of Israel’s NGO crackdown. “What is very clear is that they don’t want INGOs that do reporting,” a second senior aid worker told The New Humanitarian.

None of the organizations currently being prioritized in Gaza appear to have openly criticized Israel’s conduct, while leaders of some of the groups have outspokenly repeated Israeli talking points.

Andrzej Gasiorowski has described images of starving people in Gaza as “fake news”, “Gaza(wood)”, and “Hamas-controlled propaganda” to manufacture a “fake famine”.

Originally from Poland, Gasiorowski has become a prominent figure in the evangelical Christian movement in Israel, where he has lived since 1991. In public statements and social media posts, he has repeatedly echoed debunked Israeli claims about the death toll in Gaza, aid diversion, and UN agencies being “infiltrated” by Hamas.

In a statement to The New Humanitarian, Gasiorowski described these as efforts to address “issues of information warfare, propaganda, and documented cases of aid diversion by armed groups” and denied he was minimizing suffering in Gaza. He added that “manipulation of imagery, statistics, and narratives by armed actors is a documented aspect of modern conflict”.

Gasiorowski has also shared dozens of posts about Muslims on social media, including in an album featuring photos of beheadings by so-called Islamic State militants, among other graphic images, entitled “ISLAM – religion of ’peace’” with the description “Islam vs. the rest of the free world”. In a 2016 op-ed, he described Israel as a “tiny island in a hostile Muslim endless ocean”.

In his statement, Gasiorowski said the posts had been made “in a personal capacity” and did not reflect “hostility toward Muslims as people or toward Islam as a faith practiced peacefully by the vast majority of its adherents”. The 2016 op-ed, he added, was a “geopolitical observation about security realities and regional hostility by certain actors, not as a statement about Muslims collectively”.

In an interview published last week, GAiN’s Dewald repeated a variety of dubious claims that echo Israeli government talking points.

US-based Multifaith Alliance (MFA), another of the organizations with an expanded footprint in Gaza, has opted to limit its public communications to describing its activities. It began working in the enclave in 2024. “We try to focus on our mandate of trying to get as much aid to people who are in need… Anything that might hamper this operation, we try to avoid it,” Shadi Martini, the organization’s CEO, said in an interview with The New Humanitarian.

“We don’t think that it’s our responsibility to be political or be people who would document certain atrocities or anything. We’re not equipped even to do that,” he added. “This is a decision we made. I think it’s more helpful to the population in terms of really getting in food and shelter, and the staff, for their own well-being and survival.”

Martini said MFA currently brings between 30 and 70 trucks into Gaza daily, and sometimes up to 100. Those numbers are not tracked by the UN mechanism that most humanitarians use to coordinate and prioritize cargo entering Gaza because the MFA works outside of it, Martini noted.

Previously, MFA partnered with the Israeli military in Syria around 2016 to deliver aid and medical care. A former hospital manager in Aleppo, Martini was forced to flee Syria in 2012 because of his work coordinating medical care for civilians wounded in the beginning stages of the country’s civil war.

For him, compromising on what can be said publicly is necessary. “Do I want destruction? No. But when you are in this situation, there are priorities, and my number one priority is to have this person in Gaza to be able to stay in his land, not to be driven out,” he said. “If we don’t have people in Gaza, then our work is meaningless.”

Although MFA has chosen to abide by Israeli restrictions, Martini noted that there is no guarantee that the group will be allowed to remain: “There’s nothing preventing them from getting rid of us. They could get rid of us tomorrow.”

Unclear funding and intentions

One organization recently approved by Israeli authorities, The Sumner Foundation (TSF), had no presence in Gaza and brought no aid in until 30 December 2025, when UN data shows a surge of activity.

TSF is registered in the UK, where records show it was “set up to provide financial assistance to promising young students”. But the organization’s website describes previous work doing “search and rescue advisory” to the Philippines coast guard and “security advisory to NGOs and other operators” in Ukraine.

TSF is headed by UAE-based entrepreneur David Sumner. Among his many ventures are a now-liquidated UAE-backed investment fund, a healthcare firm entangled in a UK COVID-19 PPE procurement scandal, and a string of security and defense companies. These include UK-registered Sumner Group Defense and Sumner Global Hub; the latter provides “large scale military, border security, humanitarian aid security, pre-emptive peacekeeping & post conflict peacekeeping manpower” and other services for governments.

TSF’s board includes a former UK Conservative Party cabinet minister, several former UK and US military members (one of them a former US special forces soldier who says he worked with the CIA), and an Israeli entrepreneur, Judy Robert, whose work has included defense contracts.

UK records show the organization reported no activity in the 24 months prior to 31 March 2025, no money in the bank, and no income. The foundation’s website also didn’t mention Gaza until at least July 2025, web archives show. The website now consists of stock and archive photos, many from outside Gaza. Since the second half of 2025, TSF’s plans in Gaza have shifted from a camp for displaced people – described as “currently being established” before it was removed from the website – to soup kitchens and warehousing, and now healthcare.

Two videos posted to its website in December 2025 and January 2026 describing projects that TSF says it is planning are both composed of stock footage – some AI-generated – and unrelated images from other countries, including a US military field hospital in Türkiye after the 2023 earthquake and a COVID testing site in the UK.

In an interview with The New Humanitarian, Sumner acknowledged that the group hadn’t been actively fundraising or working on Gaza in recent years; he said that the changes of plan reflected a changing understanding of the situation and needs in Gaza.

Now, he said, the group hopes to build a field hospital in northern Gaza and eventually additional healthcare services. So far, he said, they have delivered some food to people in western Khan Younis, although they stopped importing goods in mid-January as they registered a separate, Israel-based organization to handle deliveries, which Sumner said they believed would simplify their work.

He said TSF was working with other international NGOs to provide some healthcare services, but would not say which. He refused to be more specific about the organization’s funding, but said they were raising money in the UAE and from private donors in Israel, as well as donations of medical items from the US.

Sumner would not give more information on the Israeli donors, but said they weren’t taking funding from the Israeli government. He added that TSF is also now beginning to work in Syria, where the group has made a few small deliveries, including diapers and used clothing, which they sent from Israel to an area south of Damascus. By the time this article was published, Sumner had not clarified where.

He highlighted the logistics backgrounds of his team and his own experience in healthcare staffing, which he said he believed would help to deliver aid.

Aid workers have said repeatedly since October 2023 that artificial barriers imposed by Israeli authorities – not logistics – are the main problem blocking adequate aid in Gaza.

Asked about those barriers – and about the recent decision by Israeli authorities to ban aid groups, including those doing medical work, like MSF – Sumner said: “I’ve read the articles that very clearly say that there were compliance and registration issues with a number of NGOs.” He added that he didn’t know more and didn’t want to comment.

TSF is entirely “non-political”, Sumner concluded; “What we are only focused on is trying to make some sort of difference to those people’s and individuals’ lives. In relation to the politics of what’s going on, we absolutely have no interest in it – respectfully.”

“Humanitarian camouflage”

For NGOs currently scaling up in Gaza, trying to play along with Israel’s ever-evolving rules, regulations, and diktats, in the hope of securing better access is a doomed strategy, warned Dustin Barter, a senior research fellow for the Humanitarian Policy Group at the ODI Global think tank in London.

“The notion of humanitarian pragmatism as a means to justify compromising values and principles has led to a situation where you have an open-air prison in Gaza for decades, because we continually compromise and you have this drip-feed of assistance,” Barter said. “You’re no longer alleviating humanitarian need – you’re becoming a cog in the machine of systemic oppression.”

Barter noted that authorities have strictly controlled and counted imports to Gaza for decades, down to calculating the minimum number of calories needed to keep people on the edge of starvation.

“All of this is false choices created intentionally by the Israeli state,” Barter noted. “What the hell are we doing here if we continue to prop that up?”

New groups looking to scale up in Gaza will inevitably run into the same library of Israeli tactics used to obstruct humanitarian work and push existing NGOs out – “a war of attrition through bureaucratic hell”, as a third aid worker put it recently.

Despite being allowed to operate on paper, even those with the most collegial relationships with Israeli authorities haven’t been immune to some of the same restrictions imposed on others. Data from the UN shows that deliveries from most have dropped since the beginning of the year.

This is a feature of the system, several aid workers said. “It’s a tap. They will open that tap whenever they want to, and they will close that tap whenever they want to,” the first aid worker said.

Aid workers pointed to a pattern that has emerged over the past two years: Actors who one day appear to have the favour of Israeli authorities find themselves discarded or targeted the next, whenever what one aid worker described as a “transactional” relationship no longer fits Israeli objectives, or a better option appears.

As for the second set of groups, Shahd Hammouri, an expert in international law at the University of Kent in the UK, said they appear to be willingly participating in what she described as Israeli “humanitarian camouflage”.

Hammouri and other international humanitarian law experts have argued that, rather than a well-intentioned effort to provide Palestinians in Gaza with relief, Israel is trying to create the perception that it is satisfying its legal obligation to enable aid while actually weaponizing the necessities of life to push forward a military and political agenda that directly contravenes international law.

With this approach, “they get to fulfill the obligations and the optics of the humanitarian response without giving access to the NGOs they don’t like,” said the second aid worker, who, like others, asked for anonymity to avoid retribution from Israeli authorities.

The pieces in this strategy shift frequently, making it difficult to track how exactly it is playing out on the ground from one day to the next. But the throughline is a trend towards increased Israeli control, and the limiting of recovery efforts that might allow Gaza to regain a degree of self-sufficiency, according to aid workers and experts. “This is not an aid or humanitarian project,” Hammouri said.

Riley Sparks is a Canadian journalist covering Gaza, migration, and human rights.

RELATED:

- The State Department Says Israel Isn’t Blocking Aid. Videos Show The Opposite.

- Israel gives war profiteers sole control of life-saving Gaza aid: Report

- Israel blocking outside journalists from Gaza doesn’t help its cause

- ‘Millions of dollars’ of Gaza aid stranded in warehouses as Israel rejects NGO requests for entry

- Israel isn’t just killing Palestinians seeking food aid. It’s killing people waiting in line for water, too.