Politicians from both parties regularly speak at AIPAC’s national convention. It is widely considered the most powerful organization for a foreign country in the US.

The American Israel Public Affairs Committee claimed victory in a 9-year-old legal standoff with critics of U.S. policy toward Israel. The Supreme Court ruling made it highly unlikely that the pro-Israel lobby would have to disclose information about its membership and expenditures… An attorney for AIPAC said the high court “did exactly what we asked.” Stephen Breyer wrote the opinion…

Below are four articles about the case…

AIPAC claims a victory in Supreme Court ruling

By Lauren Stein, reposted from the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, June 2, 1998 [subheads and images added]

The American Israel Public Affairs Committee claimed victory this week in a 9-year-old legal standoff with several staunch critics of U.S. policy toward Israel.

The U.S. Supreme Court, in a 6-3 ruling issued Monday, made it highly unlikely that the pro-Israel lobby will have to disclose information about its membership and expenditures — a goal that has been sought by six former politicians and diplomats.

Alleging that AIPAC made campaign contributions and expenditures on behalf of political candidates, the plaintiffs have been urging the Federal Election Commission to regulate AIPAC as a political committee — a designation that would force the organization to file public reports about all of its receipts and expenditures. But in a case being closely watched by groups that lobby in Washington, the high court chose not to rule on the status of AIPAC and instead sent the case back to the FEC. Thus the battle is not necessarily over, and the plaintiffs have vowed to press ahead with the case.

AIPAC, for its part, defines itself as a membership organization and registered lobby on behalf of legislation affecting U.S.-Israel relations — with complete freedom to communicate with its members on politics and elections.

The plaintiffs in the case included James Akins, former U.S. ambassador to Saudi Arabia, and former U.S. Rep. Paul Findley (R-Ill.), who has referred to the federal government as “Israeli-occupied territory” and blamed AIPAC for defeating his 1982 re-election bid. Akins, Findley and four other former government officials who have worked to undermine U.S. support for Israel filed suit in 1989 in an effort to convince the FEC to scrutinize AIPAC’s finances. [The other officials were Ambassador Andrew Killgore, Richard Curtiss, Robert J. Hanks, and Orin Parker.]

U.S. Court of Appeals had held that AIPAC is a political committee

In 1992, the election commission found that AIPAC spent money in an effort to influence congressional elections. But it decided not to designate AIPAC as a political action committee because it said that was not the group’s “major purpose.” The U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia rejected the FEC’s major purpose test in 1996 and held that AIPAC should be classified as a political committee because it spent more than $1,000 a year on campaigns.

According to law, a political committee is defined as “any committee” that receives or spends more than $1,000 per year for the purpose of “influencing any election for federal office.” This definition includes political action committees, which raise funds to support political candidates. AIPAC officials say the group does not make political contributions. In its Supreme Court appeal, FEC vs. Akins, the FEC argued that the plaintiffs did not have standing to bring the case; the commission argued that they had not suffered some “injury in fact” that the court could remedy.

The justices, however, ruled this week that the plaintiffs were entitled to bring the lawsuit — a move that opened the door to future lawsuits against the FEC by voters who claim the commission has not adequately enforced the financial disclosure requirements imposed by federal law on certain political groups. But the court did not rule on the merits of the claim against AIPAC, instead sending the dispute back to the FEC. In doing so, the justices left undecided the core issue that spawned the lawsuit: whether AIPAC should be considered a political committee subject to federal campaign regulations on spending and reporting.

The FEC will now decide that question based on new developments in election law and new regulations for distinguishing political committees from membership organizations. AIPAC was not a direct party in the case before the court, but the group filed a friend-of-the-court brief asking that the complaint be dismissed or that the case go back to the FEC. “We’re very pleased that the Supreme Court agreed with our view of the case,” said Thomas Hungar, a lawyer representing AIPAC. “We think” the FEC “will be forced to recognize what AIPAC has argued all along — that it’s a membership organization” that has the constitutional right to communicate with its members on any subject.

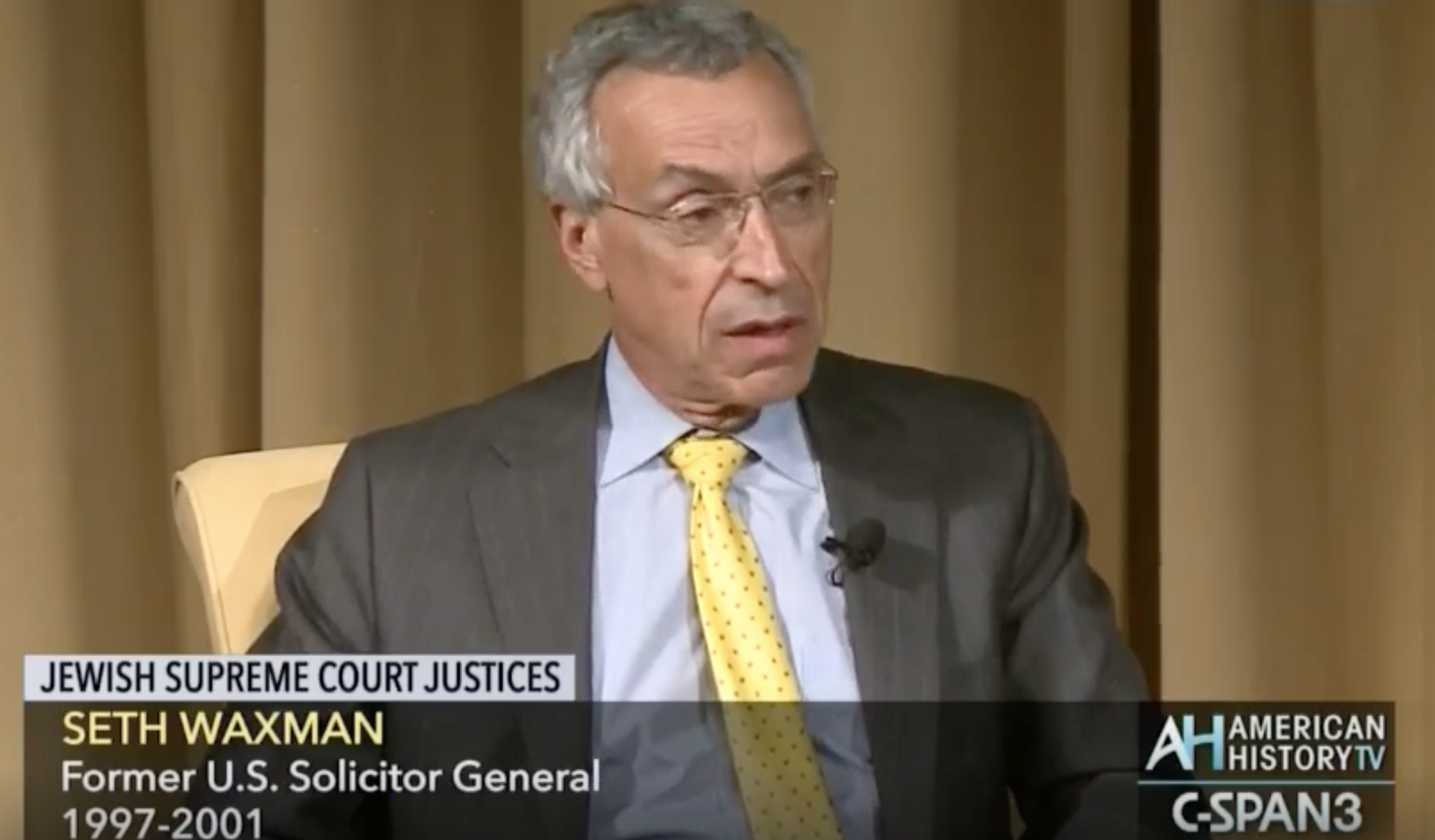

Stephen Breyer writes opinion

Justice Stephen Breyer wrote the majority opinion for the court, which was joined by Chief Justice William Rehnquist and Justices John Paul Stevens, Anthony Kennedy, David Souter and Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Justices Antonin Scalia, Sandra Day O’Connor and Clarence Thomas dissented.

[Editor’s Note: Neither Breyer nor Bader recused themselves from the case, although both are close to Israel. Bader is a lifetime member of Hadassah, the Women’s Zionist Organization of America, which advocates for Israel. Breyer is on the advisory board of an Israeli institute founded in 1991 by Bernard Marcus. (Marcus is currently an AIPAC donor.) Breyer has written that the US could allegedly learn from the Israeli court system, despite its many flaws An Israeli investigation found: “Virtually all – 99.74 percent, to be exact – of cases heard by the military courts in the territories end in a conviction.”]

In sending the dispute back to the FEC, Breyer said, “The FEC should proceed to determine whether or not AIPAC’s expenditures qualify as ‘membership communications’ and thereby fall outside the scope of ‘expenditures’ that could qualify it as a political committee.” He said new FEC rules defining membership organizations “could significantly affect” that determination. In explaining the decision to return the case to the FEC, Breyer said, “If the FEC decides that AIPAC’s activities fall within the membership’s communications exception, the matter will become moot.”

A spokesman for the FEC had no comment on the court’s ruling or what action the FEC might take, saying the commission’s attorneys were still studying this week’s decision. One of the plaintiffs, Andrew Killgore, said his group does not plan to give up. “We still hope that AIPAC will eventually have to reveal its finances as all political committees have to. That’s the goal we had from the beginning,” said Killgore, former ambassador to Qatar and the publisher of the Washington Report on Middle East Affairs, a publication that is highly critical of U.S. support for Israel.

Some legal observers, meanwhile, say the issue of AIPAC’s status remains wide open because the FEC has yet to finalize its new regulations for membership organizations. In addition, these observers say, any decision the FEC makes could now be subject to further litigation. “As much as I hate to rain on AIPAC’s party,” said Marc Stern, a lawyer with the American Jewish Congress, “it may not be tomorrow or the next day or even the next month before this matter is out of the way.”

Lauren Stein is a staff writer at Jewish Telegraphic Agency

In the Case Against AIPAC, the Gorilla Gets a Stay of Execution

By Paul Findley, reposted from Washington Report on Middle East Affairs, July-August 1998

Breyer’s decision is one of those extremely rare cases in which the high court deliberately and blatantly finessed a showdown with one of the nation’s most powerful lobbies. It did so by informing the FEC how rule changes can clear its skirts of legal trouble and then, assured that the changes are in the works, gave AIPAC absolution. The decision, of course, left AIPAC officials smiling broadly…

The U.S. Supreme Court rendered a decision on June 1 favoring six plaintiffs, including myself, in a nine-year-old lawsuit against the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC).

In reporting the decision, The New York Times described the victory as Pyrrhic, a contest won at excessive cost. I call it an ignominious judicial retreat—a predictable one—in a confrontation with one of the most powerful lobbies in the United States.

The purpose of the suit, filed in 1989, was to establish that AIPAC is a political committee within the meaning of the Federal Elections law and therefore required to disclose details of both income and expenditures.

The law defines a political committee as “any committee” that receives or spends more than $1,000 in a 12-month period with the objective of “influencing any election for federal office.”

AIPAC worked to defeat Charles Percy and Paul Findley

At the time Percy served as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. On almost any day in 1984, AIPAC expenditures aimed at influencing—that is, spoiling—Percy’s bid for re-election probably exceeded the $1,000 annual limit set by the law.

When the votes were in—with Percy among the defeated—AIPAC’s executive director, Thomas Dine, crowed about the achievement.

In 1982, AIPAC focused much of its horsepower on bringing about my defeat. I was the lobby’s number one target that year and an examination of its expenditures would surely show outlays aimed at “influencing” my bid for re-election far exceeding the $1,000 legal limit. During the same year, AIPAC weighed in heavily in Maine, helping to pull off the upset victory of George Mitchell over Representative David Emory. Mitchell had never before won an election. In a post-election call Mitchell thanked AIPAC’s Dine for his critical support and said, “I will remember you.”

In its argument before the Supreme Court, the government contended that the petitioners lacked “standing to sue” and moreover that AIPAC is not mainly a political committee and therefore exempt from the $1,000 ceiling imposed by the Federal Elections law.

The Federal Election Commission (FEC), an independent agency intended to be the watchdog that would force candidates and organizations to meet legal requirements, despite frequent pressures to the contrary, has never required AIPAC to disclose its membership, sources of income and details of expenditures. It has contended that AIPAC’s “major purpose” is non-partisan and therefore exempt from public disclosure of financial details.

Last year a lower federal court ruled against the “major purpose” test and concluded that AIPAC must be treated as a political committee by the FEC. The government appealed the decision and the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case.

Bravery and Cowardice

The Supreme Court’s decision disclosed an element of bravery on one front but cowardice on another.

By a 6-to-3 decision the high court decided that petitioners had standing to sue because we were voters and had the right to information that FEC should provide to the public.

This part of the decision was a welcome surprise, because it opened the door to future lawsuits by voters demanding withheld information.

The decision’s author, Justice Stephen G. Breyer, wrote; “The informational injury at issue here, directly related to voting, the most basic of political rights, is sufficiently concrete and specific such that the fact that it is widely shared does not deprive Congress of constitutional power to authorize its vindication in the Federal courts.”

But the decision became what The New York Times called a Pyrrhic victory for petitioners when the court, in a curious deference to future changes in FEC rules, declined to rule on whether AIPAC must report financial dealings.

Breyer’s opinion, supported by a majority of the court, did not address what the petitioners considered a fundamental if not the most important aspect of the suit, i.e., the definition of “political committee.”

Breyer’s decision avoided the definition issue because FEC was “currently considering a new rule that could make the decision irrelevant to AIPAC’s status.” Speculating that a proposed rule change by the FEC would view most AIPAC expenditures as “membership communications,” Breyer’s decision concluded that, if approved, the proposal would exempt AIPAC from the campaign law and the controversy over FEC’s “major purpose” test would no longer have importance.

Under normal circumstances, the court would be expected to rule that, under present law and existing FEC rules, the “major purpose” test is invalid. Therefore, following the normal logic of judicial decision-making, until such time as the law and/or rules are changed, AIPAC must make the required public disclosures. Instead, the court simply told the FEC how to duck the issue.

I am not an expert on Supreme Court decisions, but I will venture to guess that Breyer’s decision is one of those extremely rare cases in which the high court deliberately and blatantly finessed a showdown with one of the nation’s most powerful lobbies. It did so in a supine, abject way by informing the FEC how rule changes can clear its skirts of legal trouble and then, assured that the changes are in the works, gave AIPAC absolution.

The decision, of course, left AIPAC officials smiling broadly. Indeed, although not a party in the case before the court, AIPAC filed a friend of the court brief which suggested the precise course Breyer’s decision cited. Thomas G. Hungar, an attorney for AIPAC, said the high court “did exactly what we asked.” Under the proposed changes in FEC operations, AIPAC would “clearly qualify” as a membership group exempt from public disclosures of financial operations.

Former U.S. Ambassador Andrew 1. Killgore, one of the great stalwarts in the history of endeavors for free speech and human rights, is undismayed by the court decision. In a reaction to its decision, Killgore, the publisher and co-founder of the Washington Report on Middle East Affairs, announced that the plaintiffs will not give up their quest and predicted eventual success in forcing disclosure of AIPAC’s financial dealings.

Killgore said, “In the clear light of day, AIPAC’s activities will cease to be those of an 800-pound gorilla on Capitol Hill when it comes to U.S. policies in the Middle East.”

The New York Times gave public attention to views of both Killgore and myself. The newspaper reported that I have blamed AIPAC for my re-election defeat in 1982 and quoted me, accurately, as referring to the U.S. government as “Israeli-occupied territory.” In fact, AIPAC’s Thomas Dine has stated publicly that over 90 percent of $750,000 in funds that went to my opponent that year came from pro-Israel sources from across the country.

Although I rejoice in the challenge of the petitioners, I must state that I have never had much confidence in ultimate success. AIPAC has such muscle on Capitol Hill that, even if—a big if—the courts order financial disclosure, Congress would quickly—and quietly—enact an amendment to the election law relieving AIPAC of that requirement. Still needed is a groundswell of protest from the American countryside before AIPAC will stop acting like an 800-pound gorilla.

Former Congressman Paul Findley (R-IL) is the author of They Dare to Speak Out: People and Institutions Confront Israel’s Lobby and Deliberate Deceptions: Facing the Facts About the U.S.-Israel Relationship, both available from the AET Book Club. .

“Fiddlesticks!” Federal Judge Dismisses Case Against FEC

By Janet McMahon, reposted from Washington Report on Middle East Affairs

In a Sept. 6, 2010 decision, U.S. District Court Judge Richard J. Leon brought to an end the “case against AIPAC” filed on Jan. 12, 1989 by former ambassadors, congressmen or government officials James E. Akins, George Ball, Richard Curtiss, Paul Findley, Robert J. Hanks, Andrew Killgore and Orin Parker. In the intervening two decades three of the plaintiffs—Akins, Ball and Hanks—have died.

In his opinion, Judge Leon seemed exasperated that the seven men who brought the lawsuit against the Federal Election Commission (FEC) had not packed up their bags and gone home long ago, instead of pursuing their case all the way to the Supreme Court. “Unfortunately, this appellate odyssey had only just begun!” he wrote in describing a 1992 challenge to the FEC’s ruling that AIPAC was not a political committee—and hence not required to reveal its membership, funding sources and expenditures.

“The FEC has sole jurisdiction to civilly enforce the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971,” Judge Leon noted, the purpose of which is “to limit spending in federal election campaigns and to eliminate the actual or perceived pernicious influence over candidates for elective office that wealthy individuals or corporations could achieve by financing the ‘political warchests’ of those candidates.”

The FEC maintained that AIPAC is a “membership organization” rather than a political committee. Coincidentally, the above act specifically exempts “any communications by any membership organization…to its members…if such membership organization…is not organized primarily for the purpose of influencing the nomination for election, or election, of any individual to federal office” (the “major purpose” requirement).

The Supreme Court heard the case on Jan. 14, 1998, and issued its ruling, written by Justice Stephen Breyer, on June 1, 1998. As former Rep. Paul Findley described it in the July/August 1998 issue of the Washington Report on Middle East Affairs:

Breyer’s decision avoided the [political committee] definition issue because FEC was “currently considering a new rule that could make the decision irrelevant to AIPAC’s status.” Speculating that a proposed rule change by the FEC would view most AIPAC expenditures as “membership communications,” Breyer’s decision concluded that, if approved, the proposal would exempt AIPAC from the campaign law and the controversy over FEC’s “major purpose” test would no longer have importance.

Under normal circumstances, the court would be expected to rule that, under present law and existing FEC rules, the “major purpose” test is invalid. Therefore, following the normal logic of judicial decision-making, until such time as the law and/or rules are changed, AIPAC must make the required public disclosures. Instead, the court simply told the FEC how to duck the issue….

The decision, of course, left AIPAC officials smiling broadly. Indeed, although not a party in the case before the court, AIPAC filed a friend of the court brief which suggested the precise course Breyer’s decision cited. Thomas G. Hungar, an attorney for AIPAC, said the high court “did exactly what we asked.” Under the proposed changes in FEC operations, AIPAC would “clearly qualify” as a membership group exempt from public disclosures of financial operations.

The Supreme Court sent the case back down to the lower court, which then sent it back to the FEC, which proceeded to adopt new membership rules. As Judge Leon writes in his opinion, “The FEC found that ‘the issue of AIPAC’s political committee status during the period covered by the complaint…has, as anticipated by the U.S. Supreme Court, become effectively moot” [italics added].

Toward the end of his 25-page ruling, Judge Leon writes, “the plaintiffs argue that the combination of communications urging AIPAC members to support unidentified candidates with ‘Campaign Update’ reports that include information identifying which candidates rate best on issues relevant to AIPAC [that would be Israel] are, in effect, express advocacy. Fiddlesticks!”

We’re willing to bet that, were the judge to avail himself of the opportunity to peruse the FEC reports filed by the nearly 30 pro-Israel PACs active in the 2010 election, he’d be hard put to explain how they magically seem to give to the exact same candidates. Fiddlesticks, indeed.

SIDEBAR: From Pro-Israel PACs to Pro-Israel Foreign Nationals?

Barely six weeks after Judge Richard J. Leon dismissed Akins vs. FEC, the Federal Election Commission was sued by Canadian Benjamin Bluman and Canadian-Israeli Dr. Asenath Steiman. Both foreigners live in New York City, where Bluman is an attorney who will be sworn into the New York Bar on Nov. 22, 2010 “and intends thereafter to join the American Bar Association,” and Steiman is a medical resident at Beth Israel Medical Center and a member of the American Medical Association. Bluman currently has non-immigrant TN status, which is good for three years but can be renewed indefinitely. Steiman is in the U.S. on non-immigrant J-I status, also good for three years but subject to extension to a maximum of seven years.

The lawsuits describe both plaintiffs as “politically active,” Bluman’s causes being “protecting the environment, recognizing same-sex marriage, and ensuring that ”˜net-neutrality’ is enshrined into law.” Steiman, who was a member of the Conservative Party of Canada, “is particularly passionate about preventing a government-takover of the health-care system in the United States. She also strongly supports tax reductions and policies that encourage entrepreneurship by increasing economic liberty.” No mention is made of her position on U.S. policy toward Israel, but one rather doubts that an Israeli citizen would be indifferent to that.

Bluman and Steiman desire to “express [their] views…by contributing money to candidates for political office and by independently advocating for such candidates.” Both also expect that “over the coming years, while [they reside] in the United States, [they] will want to make…contributions and expenditures in support of other candidates for local, state and federal office.” However, the Alien Gag Law currently prevents any foreign national other than a permanent resident from making contributions to candidates or to political party committees, or from making any independent expenditure in connection with a local, state or federal election.

Bluman and Steiman argue that the Alien Gag Law violates their rights to free speech under the First Amendment to the (U.S.) Constitution.

One liberal and one conservative? From our friendly neighbor to the north? What could be the harm in that? A final question: How many Israeli citizens currently reside in the U.S.?

Janet McMahon is managing editor of the Washington Report on Middle East Affairs.

U.S. Court Orders FEC to Enforce Federal Election Law Against AIPAC

The complainants believe that if the FEC enforces its own rules, the stranglehold that Israel’s principal Washington, DC lobby has had on U.S. Middle East policy may eventually be loosened.

By Richard H. Curtiss, reposted from the Washington Report on Middle East Affairs, Jan-Feb 1997

None of the seven retired U.S. officials who filed a complaint with the Federal Election Commission in January 1988 charging that the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) and 27 named political action committees were violating federal election laws were in the bloom of youth at the time. Now, almost nine years later, when 10 judges on the U.S. Court of Appeals finally have ruled 8 to 2 in their favor, one of the complainants has died, and five of the six survivors are in their 70s.

But they exhibited quiet satisfaction at the Dec. 6 ruling, as did the lawyers who had kept the case alive over the years by donating their services, charging only for clerical and related expenses. Their demand was that the FEC follow up its own ruling that AIPAC has functioned as a “political committee” by requiring the giant pro-Israel lobbying group to disclose where it gets its now $12 million annual budget, and how it spends that money.

The complainants believe that if the FEC enforces its own rules, the stranglehold that Israel’s principal Washington, DC lobby has had on U.S. Middle East policy may eventually be loosened. Their charge is that although AIPAC has conducted itself as a political action committee, by not registering as one it has exempted itself both from disclosing publicly its receipts and expenditures, and from the federal law which restricts political action committees from donating more than $10,000 to a single candidate in a single election cycle.

They further believe, although it was not a part of the complaint to the FEC, that AIPAC has functioned as a foreign agent, openly pursuing the interests of each successive elected government of Israel, but without registering as such and thus subjecting itself to federal disclosure laws.

The complaint to the FEC, which in fact consisted of a number of separate filings, has a long and tortuous history. It was largely assembled by Abdeen Jabara, who now practices law in New York. As an activist lawyer in Detroit specializing in discrimination complaints, and during a subsequent four-year stint as president of the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee (ADC), he saw extensive evidence of violations of election laws by AIPAC officers.

The complaint to the FEC has a long and tortuous history.

The seven public figures who eventually filed the complaint were James Akins, former U.S. ambassador to Saudi Arabia; the late George Ball, Kennedy administration under secretary of state who also served the Johnson administration as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations; Richard Curtiss, former chief inspector of the U.S. Information Agency; Paul Findley, an Illinois Republican member of the House of Representatives for 22 years; Rear Admiral Robert Hanks, former commander of the U.S. Navy’s Mideast task force; Andrew Killgore, former U.S. ambassador to the state of Qatar; and Orin Parker, former president of AMIDEAST, a non-profit organization that conducts educational and training projects in the Middle East.

Some of the complainants had joined prominent journalists in writing or speaking publicly on AIPAC activities. They revealed that members of AIPAC’s national board of directors had set up a large number of political action committees in their home states. Although none of the committees mentioned Israel, the Middle East, or Zionism in their non-descriptive titles, their donation patterns to Senate and House candidates followed recommendations in a closely held “green book” circulated to some AIPAC officers and donors.

A “smoking gun” had turned up in the form of a Sept. 30, 1986 memorandum from AIPAC’s then-assistant director of political affairs, Elizabeth Schrayer, telling an AIPAC employee what to say in calls to a number of the PACs concerning their donations to named candidates. The copy of the memorandum that became public also had the employee’s own hand-written notations concerning the calls.

The result of all this was the first complaint to the FEC charging that by setting up 27 named political action committees, and then guiding their donations to specific political candidates, AIPAC itself was acting as a political action committee that should be regulated accordingly. On a Friday afternoon on the last working day of 1990, in an obvious move to avoid media attention, the FEC notified the 27 PACs that they no longer were under investigation.

AIPAC’s “Worst Nightmare”

In its report on the FEC notification, the widely read Washington Jewish Week indicated that the FEC action, in effect, dismissed the complaint. The report even quoted an unnamed AIPAC official as saying that dealing with the complaint had been the “worst nightmare” in the organization’s history.

In fact, however, there was no indication in the FEC release of its findings or actions concerning AIPAC, or of the fact reported in Jewish weekly newspapers that AIPAC was refusing to comply with the FEC’s request for financial records. As a result, the same seven complainants filed a new suit against the FEC itself, seeking to compel it to rule on the original complaint against AIPAC.

The FEC then issued a finding that AIPAC had made in-kind donations that “likely crossed the $1,000 threshold,” meaning the limitation on the amount an individual or organization can donate to a candidate in a single election, and thus functioned as a “political committee.” However, the FEC ruled, it would not require AIPAC to register as such because organizing such contributions was not “the major purpose of AIPAC.”

The seven complainants then filed a third complaint, saying that the FEC had erred in dismissing the complaint against AIPAC, and that its erroneous legal interpretation was the sole reason it exempted AIPAC from disclosing its receipts and expenditures.

When the Circuit Court of Appeals, in March 1995, found 2 to 1 against the complainants, they sought a hearing before the entire appeals court. It was this hearing on May 8, 1996, that resulted in the new decision, with 8 justices ruling for the complainants and against the FEC, and 2 dissenting. The ruling pointed out that in exempting a huge organization such as AIPAC, with its multi-million-dollar budget and some 150 employees, from observing the rules governing political activities on the grounds that such activities were not AIPAC’s “major purpose,” the FEC would open the door to very large-scale political activities conducted without the oversight imposed on other much smaller political committees.

The FEC now has several choices. It can request the U.S. solicitor general to appeal the final Circuit Court of Appeals ruling to the Supreme Court within 90 days of the ruling. Or it can order AIPAC to register as a political committee and open its financial records to the FEC in the same manner as do other political committees, which include the campaign committees of parties and candidates as well as PACs. Or the FEC can seek an injunction to stop AIPAC from making political contributions or it can fine AIPAC. AIPAC, in turn, can interpose legal defenses against FEC orders.

The complainants decline to speculate on what public disclosure of AIPAC records will reveal, both as to sources of AIPAC funding and beneficiaries of AIPAC actions. It is unlikely, however, that many members of Congress will want their constituents to learn how much support they have received through the activities of the powerful group that boasts that it “lobbies for any elected government of Israel,” particularly if the disclosures reveal that a major share of AIPAC’s direction or support has come, directly or indirectly, from foreign sources.

If that is the case, of course, it is unlikely that AIPAC will willingly turn over such records. They could spell the end of its long dominance of congressional action on U.S. military and economic aid to Israel, executive branch appointments of ambassadors to Middle East countries and positions in the State Department and other foreign affairs agencies having a bearing on U.S.-Middle East relations, transfers of military and civilian technology to Israel, and even sales and transfers of American-made military equipment to Arab and Islamic countries.

The fact that AIPAC proved unwilling to comply with the FEC’s first requests for information in 1988 indicates that there may be much in its records that the lobbying group does not want to be made public. If that remains the case, the legal action may be far from over.

The focus, however, now could shift from seven private individuals of limited means suing the powerful Federal Election Commission to that same FEC taking action against what is commonly acknowledged to be the most influential special-interest lobby in Washington, DC. Given the timidity the FEC has exhibited toward AIPAC to date, it is not at all certain that this new court ruling in favor of the plaintiffs will be enough to force the FEC to fulfill its legal mandate. If it does, however, it could change the course of U.S. Middle East policy.

Richard Curtiss was a co-founder of the American Educational Trust, which produces the Washington Report on Middle East Affairs. Mr. Curtiss, following military service in World War II, served for 30 years as a career Foreign Service Officer. He received the U.S. Information Agency’s Superior Honor Award and the Edward R. Murrow award for excellence in Public Diplomacy, USIA’s highest professional recognition. He is the author of two books on U.S.-Middle East relations. A more extensive bio can be read here.

RELATED READING:

The dark roots of AIPAC, ‘America’s Pro-Israel Lobby’

The Forward: Did AIPAC Secretly Write Your Rabbi’s Sermon?

AIPAC video describes its decades-long role in creating US laws against BDS [VIDEO]

Senator Simon Recalls AIPAC Request That He Run Against Charles Percy

Justices Hear Arguments in Suit Against Election Agency

They Dare to Speak Out: People and Institutions Confront Israel’s Lobby