A look at the history of Israel’s Film and Theater Review Board reveals its major role in shaping the cultural image of the young state – and our worldview too

by Adam Shinar, reposted from Haaretz, April 20, 2024

The war in the Gaza Strip has catapulted Israel’s Military Censor back into public discourse. The focus over the past six months has been on news items that were banned for publication, on others that, oddly, were green-lighted in order to benefit someone, and on pressure exerted on the censor by the prime minister. In October, when security considerations began to top the public agenda, the standing of the body determining whether certain items might compromise such considerations got a boost – even if it’s not always clear what might be detrimental to state security, or even what actually constitutes state security.

The institution of censorship in Israel not only strives to preserve security interests and decides what is permitted for publication. It wields great influence and plays a not-inconsiderable role in shaping the national consciousness. Its decisions – which also affect which documents in the State Archives will be declassified and open to perusal – determine what the public is allowed to know and how our knowledge of the world is forged. Clearly, information that is unpublished and hence unknown does not influence our worldview.

The military censorship, a relic of the pre-state British Mandate period, is not the only institution of this type in the country. Other blue-pencil apparatuses, official and unofficial, have always operated in Israel. One example is the Defense Ministry, which has been known to remove documents containing evidence of the Nakba from the archives, for fear of sparking unrest among Arab citizens of Israel, or of adversely affecting the state’s foreign relations. The effort to influence the attitude of the Arab community toward the state, as well as the way Israeli Jews perceive Arabs, began almost in parallel to publication of the Declaration of Independence in 1948 and played a central role in the first decades of the Jewish state.

Like its military counterpart, the Film and Theater Review Board was an inheritance from the British Mandate. Established in 1927 it resembled other apparatuses of cultural censorship the Crown created around the world. When Mandatory legislation was incorporated into the young state’s lawbooks, British censorship became Israeli. It too had the power to prevent the showing of any movie or the staging of any play.

The members of the board, an independent agency under the Ministry of Interior, consisted of civil servants – employees of the Israel Police or the Ministry of Education, for example – but also distinguished public figures, with the aim of reflecting Israeli public opinion. That ambition was realized only in part: Until the 1970s no Arab citizens served on the board, women were always in the minority and almost all of those serving were Ashkenazim. Geographical diversity was also lacking; nearly all the censors were residents of Jerusalem or Tel Aviv.

Over the years, prominent figures from the arts and the media served on the board, among them poet Haim Gouri; the founder of the Academy of Music and Dance, Yocheved Dostrovsky; and noted journalists, such as Rafik Halabi and Nahum Barnea. Joining them were lawyers, translators, politicians, directors, film critics, songwriters and authors – individuals who would not normally be thought of as harboring censorial inclinations. Another unfounded assumption.

The board worked intensively from 1948 to 1967; in some years, fully 5 percent of the films it reviewed were banned. By and large, the censorship was of the “regular” variety, mostly affecting works with sexual content. However, there were also political considerations, which can be seen as part of an effort to construct the identity of the “new Israeli,” severed from the shackles of the Diaspora.

For example, the board imposed a boycott on mounting Yiddish-language plays by Israeli theater companies from 1949 to 1951, banned German-language films and stage productions, and adopted a rigid and suspicious approach to films from Arab countries as well as other works that were seen as challenging the Zionist narrative. The censors’ aim was not only to justify the government’s actions towards its Arab community, but also to sever the identification of Jewish citizens with origins in Arab countries from those countries and to strengthen the ties of Arab citizens to the state by cutting them off from nationalist messages from the Arab world.

From the state’s inception, Arab citizens were keen to see films in their language that had been produced in Arab countries. However, a letter dated December 25, 1949 from the Interior Ministry to Yehoshua Palmon, the Arab affairs adviser in the Prime Minister’s Office, stated, “The time has not yet come to screen Arab films, because most of them are from Egypt, meaning from a hostile country.” Not long afterward, a compromise was reached under which a small number of films in Arabic could be screened, but only those purchased by Jewish immigrants before they left their countries of birth.

Similarly, only a limited number of movie theaters, in specified locations, were permitted to show films in Arabic. They included Nazareth as well as six theaters in mixed (Jewish-Arab) cities: Haifa, Acre, Jaffa, Ramle, Lod and Jerusalem. These restrictions, imposed after independence, were not lifted until 1953, following pressure by theater owners who complained they were being discriminated against and were losing income.

The country’s decision makers cited diverse reasons for their fear of allowing in Arab films. In October 1959, at a meeting of a special committee that dealt with importing such movies, a representative of the minorities department of the Interior Ministry argued in favor of limiting the number of films, claiming they were a bad influence on recent Jewish immigrants from Arab countries, who constituted the majority of the viewers of those particular movies.

A colleague from the Foreign Ministry warned at the same meeting that Arabic-language films stirred yearning and admiration for the Arab way of life and for living conditions in the Arab countries; his suggestion was to make do with American films in Arabic. An official from the Education Ministry basically agreed, maintaining that screening of Arab films should not be prohibited in Arab communities, but that for Jewish viewers they were “true poison.”

At times, the state was less concerned about the screening of Arabic-language films causing possible unrest among the Arab public, than about spurring nostalgia and longing among the Jewish newcomers from Arab lands.

In 1950, the Egyptian film “Al-Madhi al-Maghool” (“The Unknown Madhi”) was authorized for screening in Nazareth but not in Jaffa, because the movie theaters in the latter were close to Jewish neighborhoods. On another occasion, there was a suggestion that a movie be screened in Arab villages, with the aim of exposing the inhabitants to “educational culture” instead of “[wasting] their evenings in idle chatter and scheming.”

The state was less concerned about Arabic-language films causing possible unrest among the Arab public, than about spurring nostalgia among the Jewish newcomers from Arab lands.

In 1966, when the military government overseeing Israel’s Arab citizens, which had been in effect since 1948, was abolished, the Film and Theater Review Board reassessed the situation. It concluded that the longings of Jews with roots in Arab countries for their old homelands was now less critical, as the young generation felt more connected to the state and anyway preferred American movies. The problem at hand was Arab nationalism and its impact on Israel’s Arab population. As early as 1961, the prime minister’s adviser on Arab affairs, Uri Lubrani, said he had been promised, most likely by the board, that newsreels screened in theaters in Arab locales would no longer show footage of Egyptian President Gamal Abdul Nasser. The reason: There are “jubilant outcries and shouts of encouragement in Arab movie theaters when Nasser appeared on the screen.”

This approach also continued after the Military Government was abolished. Immediately afterward, the new adviser on minorities in the Prime Minister’s Office, Shmuel Toledano, declared that he favored permitting Arabic-language films to be screened – but only in Arab locales. In their free time, he said, it would be better for Arab citizens to see such films – albeit only those without nationalist messages that had been approved by the censors – than to have them viewing content on television from neighboring Arab countries, over which Israel had no control.

In addition, Toledano noted, Israel had a “general interest in preventing the importation of Arab films for the Jewish population.” It was, as Levi Geri, chairman of the review board, had said, impossible to limit films to Arab moviegoers alone – in any case, “only the elders of the Mizrahi communities” (i.e., Jews with origins in Middle East or North African Countries) want to see Arab films, he added.

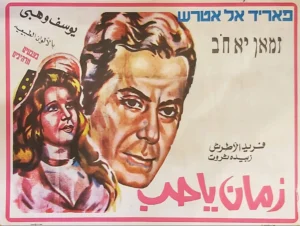

Throughout this period, Israeli society debated whether such films should be screened at all in the country; people wrote to the board and to the newspapers, arguing for and against. In a letter to the censors, a woman named Pnina Semyonsky wrote in 1959 that movies starring the popular singer-actor Farid al-Atrash were “totally lacking in content, and I don’t understand the point of screening them. Considering the number of Arabs in our country, there is no need for the mass distribution of Arab films… I’m certain that the immigrants from the Middle Eastern lands enjoy English, American and French films – there’s no need to show them Arab films.”

For his part, Geri dismissed the writer’s views: “The Arabic-speaking population in Israel demands, and rightfully so, to see these films. The films that were approved for screening are the most lukewarm type of Middle Eastern entertainment, and are not flawed morally or in any other way. We are not boycotting Arab culture, and Jews do not hate Arabs.”

A year later, Yitzhak Shraga, a resident of the Bukharan neighborhood in Jerusalem, castigated the Interior Ministry (i.e., the board) for its intention to prohibit the screening of films from Arab countries in Israel. “I would like to ask you why the Mizrahi communities should be deprived of the only entertainment they have, whereas Austrian and German films are permitted. I understand that we want to fight the Arab countries’ boycott [of Israel] with our own boycott, but in this case only the Mizrahi communities are deprived, because this is the only entertainment they can be shown. And in addition, we need to show the world that we are not fanatical and that we will allow Arab films to be screened so there will be no hatred between the country’s Arabs and us [Jewish citizens], and no one will think we are discriminating against them in particular.”

The issue of Arab films was partially resolved, or rather became largely superfluous, due to two developments. First, about the time television broadcasts officially began in Israel, in the late 1960s, it became possible to view stations from Arab countries, thus bypassing Israeli censorship. Second, some of the obstacles in this regard were removed in the wake of Israel’s 1967 conquest of the West Bank, to which Arab films flowed freely; plus, with the annexation of East Jerusalem, films screened there could no longer be considered as originating in an enemy state. Despite this, the Film and Theater Review Board still had to weigh in on the screening of every single Arabic-language film, and some were banned. Here matters became more complicated, and considerations of national ethos became more prominent.

Undesirable associations

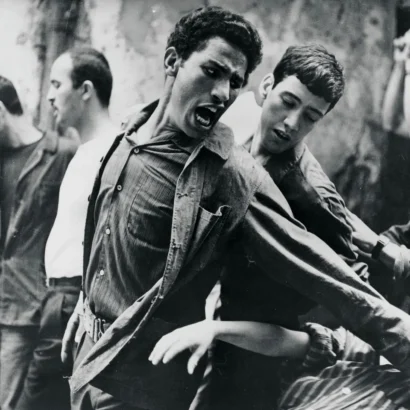

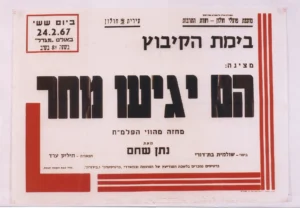

As part of its efforts to assess the impact of artistic works on the Jewish public, the board in 1950 discussed Nathan Shaham’s play “They’ll Be Here Tomorrow,” based on his short story “Seven of Them,” set during the War of Independence. Its production was approved, but on condition that two scenes be cut because they were deemed harmful to national morale.

One scene dealt with the treatment of a captive from an Arab country – whom one of the characters wanted to exploit to search for land mines – and the other was about the fear Israeli soldiers feel in war. The board thought that it was inappropriate to play up such fears as they could affect potential draftees. The full version wasn’t staged until 1972. Shaham’s play, however, was an unusual case – most of the movies and the plays the board reviewed were not Israeli works. In any event, few Israeli playwrights or filmmakers were dealing during those years with the Palestinian conflict and the occupation. Most of what was considered controversial, from abroad, involved content relating to Israel or issues that were seen to have a possibly adverse influence over its citizens. But the occupation of the Palestinian territories itself marked continued Israeli vigilance vis-à-vis Arab culture.

In 1968, the censors banned “The Battle of Algiers,” a highly acclaimed Italian-Algerian feature film about the resistance to the French occupation in Algeria. In justifying the decision, the board chairman at the time, Zeev Milion, wrote: “The film depicts the operations of the underground [the FLN] against the French. It presents the heroism of Arab terrorists very sympathetically, and as such its content is liable to encourage those in our country who have an interest in taking an ‘example’ from the methods of combat in the underground, and even providing such ideas for such means of combat. Accordingly, the movie is banned for screening in Israel.”

Levi Geri seconded this opinion, and both censors agreed that, “the film glorifies the underground fighters in Algiers and stirs undesirable associations with the situation in the country today.” A few years later the board reversed its own decision and the film was screened.

Focusing on the military censor ignores the self-censorship that has taken hold in the mainstream media and its unwillingness to hold a critical discussion of the humanitarian situation in Gaza.

In 1979, the censors banned the Egyptian film “Behind the Sun.” Commissioned by the regime of President Anwar Sadat, the plot centered around criticism of the authorities’ failure to win the 1967 war against Israel. The film depicts Nasser loyalists responding violently to the criticism and focuses on the torture they endured at the hands of the brutal and corrupt security apparatuses.

The Israeli censors thought that screenings of the movie could have negative repercussions in the West Bank. Their decision was based in part on the opinion of Ovadia Danon, a Mossad operative in Alexandria in the 1950s, who helped recruit a squad tasked with sabotaging Egypt’s relations with Western countries (in the so-called failed Lavon Affair). Danon thought that the movie might help dissuade inhabitants of the territories from perpetrating acts of terror or violence, but could also inspire students and the educated classes there to rebel against Israeli rule.

The interior minister’s adviser on Arab affairs, David Agmon, wrote that “Behind the Sun” would “encourage the irrational elements among the Arabs in Israel and the territories to intensify their resistance to the authorities.” However, in response to those who claimed that it was important to allow the film to be screened, to show that Israel behaves differently from the Arab states, he maintained that Israeli actions were also repressive – but still believed the movie should be banned.

In the same year, the board also banned an Israeli drama, “The Lost Peace,” by Palestinian-Israeli playwright Radi Shehadeh about Jewish-Arab relations within Israel, particularly issues of discrimination and distributive justice. Initially, the censors were divided. Board member Mordechai Bibi, a former Labor MK, thought the play was inflammatory, depicting only Israel’s wrongdoings. Still, he thought it should be staged, if only “to put the Arab public to a test, to determine to what extent it is susceptible to the influences of incitement and hostility against the state.” For his part, Druze journalist Rafik Halabi rejected Bibi’s idea of putting Arab citizens to a test, but observed that if the film indeed constituted a source of incitement, the matter should be looked into by the security authorities.

Moshe Sharon, the Arab affairs adviser in the Prime Minister’s Office, was emphatic. The play was full of hatred, its aim was to fan the flames of hostility toward the state and to portray the Jews as occupiers, foreigners, oppressors and usurpers. The majority of the board eventually agreed with him and the play was banned.

In general, during those years, the Supreme Court did not intervene in the work of the country’s most important cultural gatekeeper, which sought to reflect and shape the national ethos of the time. In 1979, the court, sitting as the High Court of Justice, denied a petition against the review board’s ban on the documentary film “The Struggle for the Land, or Palestine in Israel,” about the demolition of Arab villages and expropriation of their land during the Nakba in 1947-49, when 700,000 Arabs fled or were expelled. In the board’s view, the film’s portrayal of Israel and the Zionist vision was twisted.

Justice Moshe Landau, who heard the petition, sought to refute the film’s findings and pointed out its lack of balance. He reprimanded the filmmakers for not explaining that some Palestinians had fled at the instruction of their leaders and that land in Petah Tikva and Tel Aviv had been purchased from Arabs, and explained that the film might incite “a sympathetic reaction among young Jews who ‘knew not Joseph’ and averted their eyes to seeing the real truth of our time.”

In other instances, the court laconically rejected other petitions against the censors’ rulings, such as in the case of “The Lost Peace,” which the board originally deemed to be inflammatory and unbalanced.

It was not until the 1980s that the top court’s noninterventionist policy shifted. This was fomented largely by Justice Aharon Barak, whose rulings were aimed at ensuring freedom of expression and brought about the enfeeblement of the censorship board. In 1987, the board’s ban on Yitzhak Laor’s 1984 play “Ephraim Goes Back to the Army” was lifted, due to a High Court ruling.

The last film the board banned was Mohammad Bakri’s “Jenin, Jenin,” in 2002 – a decision that was also overturned by the High Court.

Essentially, the Film and Theater Review Board became a dead letter after 1991, after permission to censor works was repealed by the Knesset, as a result of Supreme Court intervention. Today the board’s only role in practice is to rate movies according to the appropriate age group.

The fighting in Gaza, however, has sparked a public discussion of the media’s role in covering the war. Focusing on the official military censor, with whom this article began, misses the point – namely, it ignores the self-censorship that has taken hold in the mainstream media and its unwillingness to hold a critical discussion of the humanitarian situation in Gaza, and of the aims of the war and its conduct. Discourse on such subjects is playing out in the foreign media but is largely absent from Israel’s domestic arena. But then shutting our eyes to the situation in the territories isn’t new, nor is our lack of interest in the Arab citizens of our country.

This approach was also, however, bolstered by an official policy of censorship of the arts in Israel for many years, during which numerous discussions were devoted to the implications movies and plays could have on relations between the Jewish and Arab communities in Israel proper, and later also in the occupied territories. Censorship as it existed then ended some time ago, but it has been succeeded by ad hoc and informal mechanisms that are equally potent. Perhaps even more so.

Adam Shinar is a professor of constitutional law at the Harry Radzyner Law School at Reichman University.

RELATED:

- The Magic of Israel: Censorship, Now you see it, now you don’t

- As Twitter censorship is revealed, will Palestine remain canceled?

- Facebook report concludes company censorship violated Palestinian human rights

- CENSORSHIP: Google deletes Press TV from YouTube

- Facebook COO pledges $2.5 mill to Israel advocacy group, brushing off Palestinian complaints of censorship