Alan Leveritt, publisher of the Arkansas Times. Brian Chilson / Arkansas Times

In Arkansas, a newspaper publisher is in financial straits after refusing to sign an anti-BDS pledge. He believes that political dissent is protected speech, and that the Arkansas law violates his constitutional rights and his journalistic ethics.

Boycott, Divest and Sanction (BDS) is a nonviolent, grassroots Palestinian movement designed to put pressure on Israel to end its oppression and occupation of Palestinians. The movement is modeled after the boycott campaign that ended apartheid in South Africa.

Anti-BDS laws – considered blatantly unconstitutional by the ACLU – have sprung up in dozens of states, and have been challenged regularly.

When letters first showed up on Alan Leveritt’s desk saying the Arkansas Times was required to sign a pledge not to boycott Israel in order to continue to receive state contracts, he ignored them.

“I was frankly not aware there was a boycott of Israel when I started getting these notices,” Leveritt told NBC News.

As the publisher of the Arkansas Times, a monthly magazine based in Little Rock, he relies on advertisement revenue from state entities to keep his business afloat.

“Publishing a newspaper is not a lucrative business right now,” he said, adding that he’d hoped the letters would just “go away.”

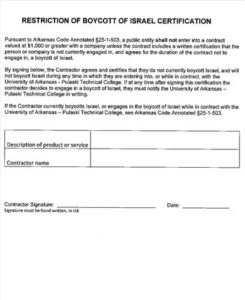

But eventually, a purchasing manager at the University of Arkansas-Pulaski Technical College, who Leveritt pointed out was “just going by the letter of the law,” insisted that he sign the pledge to retain their ad revenue.

The purchasing manager was following Act 710, a 2017 bill passed in the Arkansas Legislature “to prohibit public entities from contracting with and investing in companies that boycott Israel.”

This means that if a company wanted a state contract over $1,000, the public entity granting the contract had to certify that the company does not participate in a boycott of Israel. If a company doesn’t sign the pledge, Arkansas law allows it to still receive a contract if it offers its services at a reduction of at least 20 percent.

Act 710 was passed as a way for the Arkansas Legislature to affirm its support for Israel and respond to the BDS movement, a growing pro-Palestinian effort which calls for boycotts, divestment and sanctions against Israel to secure Palestinian rights.

While Leveritt isn’t shy in saying the Arkansas Times leans “left of center,” neither he nor the publication has ever supported a boycott of Israel or the broader BDS movement.

“We don’t have a dog in that hunt,” Leveritt said. “We are a lot more interested in Medicaid expansion than we are Jerusalem.”

But now a geopolitical issue he felt like he had no stake in was affecting his already precarious small business.

Leveritt thought about signing the pledge. “To have something like this thrown on top of you is enough to capsize the boat,” he said. Ultimately, Leveritt said he couldn’t go through with it, though.

He believed being forced to sign a pledge like the one Act 710 mandated violated his constitutional rights and his journalistic ethics.

The Times lost around $13,000 on the Pulaski Tech account in three months, and Leveritt teamed up with the American Civil Liberties Union, which sued the University of Arkansas System’s board of trustees on his behalf.

AN ISSUE BEYOND ARKANSAS

Arkansas is one of more than 25 states that have passed legislation meant to curtail the BDS movement, and around 15 more have seen anti-BDS legislation introduced in their state chambers.

Republican State Sen. Bart Hester introduced Act 710 to Arkansas’ Senate as a co-sponsor. “It’s a very, very small step but it’s what we could do as the state of Arkansas,” Hester told NBC News. “When one state does it, it’s not much, but when 35 or 40 or 50 states do it, it starts to send a message.”

Earlier this month, anti-BDS legislation went national when the U.S. Senate passed the Combating BDS Act, which encourages states to enact legislation like Act 710. It passed with support from groups such as the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, or AIPAC, and Christians United For Israel. Other national legislation, like the Israel Anti-Boycott Act, also exists.

The ACLU, which does not take a position on boycotts of Israel or any other nation but maintains boycotts are “protected expression,” successfully sued Arizona and Kansas for their respective anti-BDS laws. In Arkansas, they came up short.

Filing a preliminary injunction to block the law as the case proceeded, the ACLU argued Act 710 violates the First Amendment rights of the Arkansas people because political boycott is protected expression.

The defendants, the University of Arkansas System, referred the matter to Arkansas Attorney General Leslie Rutledge, whose office filed for the Arkansas Times’ case to be dismissed. (A university representative said it does not comment on pending litigation.)

In January, a federal district judge both denied the ACLU’s request for an injunction and dismissed the case outright, saying because “engaging in a boycott of Israel, as defined by Act 710, is neither speech nor inherently expressive conduct, it is not protected by the First Amendment.” On Feb. 21, the ACLU appealed the case to the Eighth Circuit Court.

Brian Hauss, the ACLU’s lead attorney on the case, said, “you can’t condition government contracts on the forfeiture of First Amendment rights and make people choose between their livelihoods and their First Amendments rights.”

A spokesperson for Rutledge’s office, however, said: “Attorney General Rutledge is confident that the Eighth Circuit will affirm the district court’s well-reasoned decision dismissing the Arkansas Times’s meritless lawsuit.”

IfNotNow, a progressive Jewish group that does not take a stance on the BDS movement, opposes state bills like Act 710, calling them “thinly veiled attempt[s] to use state power to silence political dissent.”

“Criminalizing peaceful protest is morally unjustifiable no matter your views on BDS,” the group said.

WHAT COUNTS AS PROTECTED SPEECH?

While much of the debate around BDS centers on whether the movement is discriminatory against Jewish people — something its critics proclaim and its supporters, many of whom are Jewish, vehemently deny — at the crux of the ACLU’s lawsuit is a different issue: Is there a constitutionally protected right to political boycott?

Alyza Lewin, president and general counsel of the Louis D. Brandeis Center for Human Rights Under Law, said there is a difference between promoting BDS, which she says is protected speech, and engaging in BDS. She said she believes the act of boycotting Israel is not protected by the First Amendment, and the Brandeis Center says legislation like Act 710 does not violate free speech.

“There is no unqualified right to a political boycott,” Lewin said. She believes the ACLU is “conflating speech with conduct” and is falsely arguing the government “must subsidize discriminatory conduct.”

Ramya Krishnan, a staff attorney at the Knight First Amendment Institute of Columbia University, disagrees.

“The Supreme Court held almost four decades ago that politically motivated consumer boycotts are a form of protected free speech,” Krishnan said.

Krishnan was citing NAACP vs. Claiborne Hardware, the landmark 1982 civil rights case that said “while states have broad power to regulate economic activity,” the First Amendment protects those who use boycotts to “bring about political, social, and economic change.”

It’s clear, Hauss said, that people participating in boycotts of Israel are doing it for political reasons, emphasizing that none of the ACLU’s clients who oppose anti-BDS legislation have ever profited from their boycott.

Lewin said statutes like Act 710 don’t “have any impact on [Leveritt’s] speech at all.”

“The only thing that it would restrict is the purchasing decisions,” she said. “If the conduct requires explanation, the explanation is the speech, but the conduct itself, the purchasing power, that’s not speech.”

That’s why Lewin thinks “these statutes are really anti-discrimination laws.”

Hauss doesn’t buy that claim.

Because the anti-BDS bills only focus on Israel, Hauss said they “are not really interested in preventing discrimination.”

“They are interested in preventing a certain kind of expression that the government doesn’t like,” Hauss said, “which is of course why they’re called anti-BDS laws and not nationality discrimination laws.”

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS FOR ARKANSAS TIMES

Amid the legal debate and court battles of the past year, the Arkansas Times had the worst year of its history after it decided not to sign the pledge, Leveritt said. Losing contracts like Pulaski Tech is “real money to us,” he added.

As the court case continues, he’s worried about the future of his company. “We have 35 families depending on this newspaper for a living,” Leveritt said.

Yet he remains steadfast in his decision to not sign the pledge.

“You know, we weren’t looking for a fight,” Leveritt explained. “We have sometimes been on the wrong side of break even. We didn’t want any trouble.”

But the second you sign a pledge like the one state agencies were demanding he sign, Leveritt said, “You’re not a journalist anymore. You’re in public relations.”

RELATED READING:

Tennessee “fights anti-Semitism” by passing resolution supporting Israel

Poll: 75% of Americans Oppose Outlawing Boycotts of Israel

Arizona university forces speakers to sign pledge they don’t boycott Israel

Israeli Government creates $72 million joint program for rapid BDS response