Below are highly diverse articles about Trump’s recent statements saying that the US will take over Gaza, move its almost two million inhabitants out, then completely rebuild it.

Who would then live there, Trump was asked? “Palestinians” and “the world.”

Meanwhile, Palestinians in Gaza expressed their deep connection to the land and plans to stay – no matter what.

The final article below suggests a real solution to the Gaza “problem”: The refugees return to their original homes in what used to be called Palestine and is now named Israel… a thorough analysis by a scholar shows that this is possible.

Trump, in Shock Announcement, Says U.S. Will Take Over Gaza After Permanently Displacing Palestinians

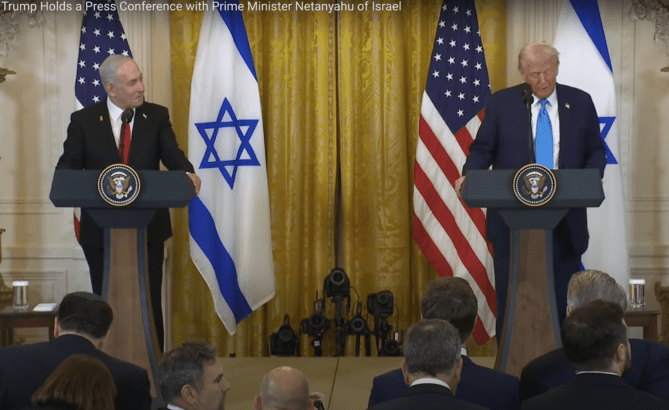

The U.S. President unveiled his plan at a White House press conference with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who immediately endorsed the plan, saying ‘Trump is taking it to a much higher level’

By Ben Samuels and Liza Rozovsky, reposted from Ha’aretz

WASHINGTON – U.S. President Donald Trump made the shocking announcement on Tuesday during a joint press conference with visiting Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu that he will pursue a plan where the U.S. assumes ownership of Gaza, shortly after calling for the permanent displacement of the Strip’s residents.

“The U.S. will take over the Gaza Strip and we’ll do a good job with it too. We’ll own it and be responsible for dismantling all the dangerous unexploded bombs and other weapons on the site, level the site and get rid of the destroyed buildings, level it out and create economic development that will supply unlimited numbers of jobs and housing for the people of the area,” he said.

Trump stressed that “I also strongly believe the Gaza Strip, which has been a symbol of death and destruction for so many decades and so bad for the people anywhere near it and those who live there. It’s been very unlucky for a long time. Being in its presence has just not been good. It should not go through a process of rebuilding and occupation by the same people that have stood there and fought for it and lived there and died there and lived a miserable existence there.”

“We should go to other countries of interest with humanitarian hearts – there are many of them that want to do this – and build various domains that will ultimately be occupied by the 1.8 million Palestinians of Gaza ending the death and destruction and frankly bad luck,” he continued. “It could be 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 12, numerous sites or one large site. But the people will be able to live in comfort and peace. They’re going to have peace, not shot at, killed and destroyed like this civilization of wonderful people have had to endure.”

[Editor’s note: at this time, the countries Trump has mentioned – Egypt, Jordan, Indonesia, and others – have rejected the idea of accepting the Palestinians. Nor have the Palestinians in Gaza consented to this idea. The movement of the people would be “forced transfer,” which is a crime against humanity.]

When asked if this meant that Trump would send U.S. troops to Gaza, he said “if it’s necessary, we’ll do that. We’re gonna take over that piece and develop it, create thousands and thousands of jobs. It will be something the entire Middle East can be very proud of.”

“I see a long-term ownership position and bringing great stability to that part of the Middle East. Everybody I’ve spoken to – this was not a decision made lightly – everybody loves the idea of the U.S. owning that piece of land, developing and creating thousands of jobs with something that will be magnificent in a magnificent area nobody would really know. They look and all they see is death and destruction and rubble,” he said. “I’ve studied this very closely, and I’ve seen it from every different angle. And it’s only going to get worse.”

[Editor’s note: Trump does not mention that the current and previous devastation was caused by Israel.]

Trump deemed Gaza “a hellhole – it was before the bombing started, frankly. And we’re going to give people a chance,” adding that “I’ve spoken with other leaders in the Middle East, and they love the idea, they say it will really bring stability.”

Qualifying that he didn’t want to be “cute” or a “wise guy,” he described Gaza as the potential “Riviera of the Middle East. This could be so magnificent, but more importantly is the people absolutely destroyed can live in a much better situation.”

“I envision the world’s people living there. You’ll make it into an international, unbelievable place. The entire world will be there – Palestinians also – many people will live there. They tried the other for decades and decades, it’s not gonna work.”

Netanyahu immediately endorsed the plan, saying, “President Trump is taking it to a much higher level. He sees a different future for that piece of land that has been the focus of so much terrorism and attacks against us, so many trials and tribulations. He has a different idea, and it’s worth paying attention to this. He’s exploring it, and it’s something that could change history.”

The news was so shocking that it distracted from the fact that Trump said he would make a decision on Israel’s potential annexation of the West Bank within the next four weeks – a potential paradigm shifting event for the entire Middle East.

He additionally expressed tacit support for the hostage deal, saying “we’re taking them out, and we’ll go into phase 2, but we’d like to get all the hostages. If we don’t, it will make us somewhat more violent, I’ll tell you that, because they would have broken their word.”

Population Transfers Approved by America? It’s on the Table.

By Daniel Levy, reposted from the New York Times, Feb.4

President Trump has introduced a seemingly game-changing, if incendiary, proposal ahead of his meeting on Tuesday with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel, the first foreign leader he will meet since his inauguration. Three times in less than two weeks, Mr. Trump has suggested that Palestinians could be relocated from Gaza to Egypt and Jordan.

It is hard to exaggerate the traumatic resonance of displacement and population transfer in collective Palestinian memory. This history helps explain the Palestinian determination to remain in the newly devastated territory and the widespread outcry to this relocation proposal and its long-term radicalizing potential.

If the two leaders take this idea seriously in their meeting, and, worse, if the idea comes to fruition, it will almost certainly boost hostility to Israel in the region and kick any prospects of U.S.-sponsored Israeli-Saudi normalization — a goal Mr. Trump enthusiastically seeks to pursue — deep into the long grass. The Saudi leadership recently joined many others in designating Israel’s actions in Gaza a genocide and has become more forceful in conditioning normalizing ties on the creation of a Palestinian state. Aside from being morally reprehensible, a large-scale population transfer of Palestinians would very likely close the door on a three-way U.S.-Israel-Saudi deal for the foreseeable future.

Having put the idea out there, Mr. Trump may think the storm that followed gives him leverage. He may assume that Arab leaders — in classic transactional terms — could give him something in return if he drops it. The idea has a potentially beneficial domestic political angle for Mr. Netanyahu. It holds strong appeal to the right-wing allies that his coalition government depends on and for whom continuing the Nakba — the expulsion and flight of Palestinians around Israel’s creation in 1948 — seems to be an ideological goal. These potential benefits will neither last long nor get them very far.

Mr. Trump’s relocation idea joins a long list of Washington’s illusions about settling the conflict in the Middle East: that Israel is more likely to make peace if treated with indulgence in response to accusations of violations of international law; that resistance to Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories has a military solution; and that normalizing Israel’s relations with Arab states, with which it is not in conflict, can work as an end run around dealing with Palestinian dispossession and denial of self-determination and rights.

[Editor’s note: Netanyahu stands accused of war crimes before the International Criminal Court; Israel stands accused of genocide before the International Court of Justice. It is also worth noting here that International law supports the efforts of resistance groups against an occupying power, even to the point of armed resistance.]

In the current environment, suggestions of depopulation, whether intended as a practical proposition or not, cannot be taken lightly. This is not only because of the history of partition and displacement. It is also because of what is happening now. Shortly after the Hamas attack of Oct. 7, as Israel expanded its military operations in Gaza, reports surfaced that the government had floated plans — later downplayed by Mr. Netanyahu — to force Palestinians out of Gaza and into Egypt. Proposals of “voluntary” mass emigration of Palestinians have also been aired in Israeli political circles, including by senior officials.

Following Mr. Trump’s recent comments, Israel’s extreme nationalist finance minister, Bezalel Smotrich, promised to submit an “operational plan” to the government for carrying out the relocation. He and other extremists have repeatedly promoted Israeli-Jewish settlement of Gaza.

These displacement plans do not end with Gaza. The West Bank, where Israel is escalating military operations, is considered by many right-wing extremists in Israel to be the real prize, and Jordan the preferred destination for Palestinians living there.

None of this offers a future of security for Israelis, either. They risk creating an even more destabilized environment for those neighbors being called on to absorb the relocated Palestinians, and the displacements would serve as a rallying cry and recruitment lure for resistance movements across the region.

Of course, Mr. Trump is well known for his bluster, and it is far from clear whether he and Mr. Netanyahu will make this a priority in their meeting. But what if the goal is to actually see this through to implementation? A number of current Trump administration nominees, including Elise Stefanik, to be the ambassador to the United Nations, and Mike Huckabee, to be the ambassador to Israel, openly advocate a greater Israel that belongs to the Jews only. Can it even be done?

Gaza, in many ways, is indeed the demolition site that Mr. Trump has described. Israel’s military campaign has laid waste to 90 percent of the housing stock, most public infrastructure, schools, hospitals, mosques, churches and governmental buildings. If the guns continue to stay silent and Palestinians see no horizon of hope, or even if war resumes, might an atmosphere be created that is more conducive to mass exit? Could the degree of economic aid and military dependence that Jordan and Egypt have on the United States tip the balance?

Probably not. Israel has failed to defeat either Hamas or crush the determination of the Palestinian people. It is hard to find a starker contrast than that between the words uttered by the U.S. president and the resilience of the Palestinian population, as hundreds of thousands have made their way back to northern Gaza in recent days, determined to rebuild their lives.

There is nothing to suggest that Arab states would either fund such an act of displacement or play any role in it, including as recipient countries, despite Mr. Trump’s claim of Egypt and Jordan, “They will do it.” Quite the opposite — all have come out staunchly in opposition, most recently this weekend at a meeting in Cairo of key Arab foreign ministers, who, in a joint statement, rejected “any efforts to encourage the transfer or uprooting of Palestinians from their land, under any circumstances or justifications.”

There is profound contradiction in hearing a president who prides himself on deportations and closing his own borders to migration being so generous in volunteering third countries as recipients of population transfers.

It is even harder to make the case that removing Palestinians should become a policy priority for the U.S. government. After all, what possible core national security interest could it serve? Whatever else there is to say about plans to acquire Greenland or the Panama Canal, America, at least, would be the end beneficiary. Helping to ethnically cleanse Gaza of Palestinians? Not so much. It would only further lacerate America’s standing in the world.

Trump’s Gaza Plan Is Unworkable, Analysts Say. Does He Really Mean It?

President Trump’s proposal to transfer millions of people out of Gaza was hailed by the Israeli right and condemned by Palestinians. Some experts say it may be a negotiating tactic.

By Patrick Kingsley, reposted from New York Times, Feb. 5

President Trump’s plan to place Gaza under American occupation and transfer its two million Palestinian residents has delighted the Israeli right, horrified Palestinians, shocked America’s Arab allies and confounded regional analysts who saw it as unworkable.

For some experts, the idea felt so unlikely — would Mr. Trump really risk American troops in another intractable battle against militant Islamists in the Middle East? — that they wondered if it was simply the opening bid in a new round of negotiations over Gaza’s future.

To the Israeli right, Mr. Trump’s plan unraveled decades of unwelcome orthodoxy on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, raising the possibility of negating the militant threat in Gaza without the need to create a Palestinian state. In particular, settler leaders hailed it as a route by which they might ultimately resettle Gaza with Jewish civilians — a long-held desire.

To Palestinians, the proposal would constitute ethnic cleansing on a more terrifying scale than any displacement they have experienced since 1948, when roughly 800,000 Arabs were expelled or forced to flee during the wars surrounding the creation of the Jewish state.

“Outrageous,” said Prof. Mkhaimar Abusada, a Palestinian political analyst from Gaza who was displaced from his home during the war. “Palestinians would rather live in tents next to their destroyed homes rather than relocate to another place.”

“Very important,” wrote Itamar Ben-Gvir, a far-right Israeli lawmaker and settler leader, in a social media post. “The only solution to Gaza is to encourage the migration of Gazans.”

“Comical,” said Alon Pinkas, a political commentator and former Israeli ambassador. “This makes annexing Canada and buying Greenland seem much more practical in comparison.”

But it is the very outlandishness of the plan that signaled to some that it was not meant to be taken literally.

Just as Mr. Trump has often made bold threats elsewhere that he ultimately has not enacted, some saw his gambit in Gaza as a negotiating tactic aimed at forcing compromises from both Hamas and from Arab leaders.

In Gaza, Hamas has yet to agree to fully cede power, a position that makes the Israeli government less likely to extend the cease-fire. Elsewhere in the region, Saudi Arabia is refusing to normalize ties with Israel, or help with Gaza’s postwar governance, unless Israel agrees to the creation of a Palestinian state.

Mr. Trump’s maximalist plans may have been an attempt to get both sides to shift their positions, Israeli and Palestinian analysts said.

Faced with a choice between preserving its own control over Gaza and maintaining a Palestinian presence there, Hamas might perhaps settle for the latter, according to Michael Milshtein, an Israeli analyst of Palestinian affairs.

And Saudi Arabia is being prodded to give up its insistence on Palestinian statehood and settle instead for a deal that preserves Palestinians’ right to stay in Gaza but not their right to sovereignty, according to Professor Abusada, the Palestinian political scientist.

Saudi Arabia swiftly rejected Mr. Trump’s plan on Wednesday, issuing a statement that underlined its support for Palestinian statehood. But some still think the Saudi position could change. During Mr. Trump’s previous tenure, in 2020, the United Arab Emirates made a similar compromise when it agreed to normalize ties with Israel in exchange for the postponement of Israel’s annexation of the West Bank.

“Trump is showing maximum pressure against Hamas to scare them, so they make real concessions,” Professor Abusada said. “I also think he is using maximum pressure against the region, so they would settle for less in exchange for normalization with Israel. Exactly like what the U.A.E. did.”

In turn, Mr. Trump has given the Israeli right a reason to support an extension of the cease-fire, Israeli analysts said.

For more than a year, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s right-wing allies have threatened to collapse his coalition if the war ends with Hamas still in power. Now, those hard-liners have an off-ramp — a pledge from Israel’s biggest ally to empty Gaza of Palestinians at some point in the future.

Nadav Shtrauchler, a former adviser to Mr. Netanyahu, referring to those right-wing elements, said, “In time, they will need to see some evidence that it is actually happening.”

But for now, he added, “They will be more patient.”

Kissing the ground in Gaza’s north

By Moaas Redwan, reposted from Electronic Intifada

After 15 months, the declaration of a ceasefire was finally announced, with the most important condition being the return of displaced people to their homes in Gaza’s north.

I had been displaced from Jabaliya refugee camp in the north to Khan Younis, then to Rafah and finally to Deir al-Balah.

Even if we were returning to rubble, the priority was to go back. It was announced that displaced people would be able to start going back north on Sunday, 26 January, after a week of the ceasefire agreement taking effect.

Everyone was waiting for this day with great excitement and joy – the day we would return to northern Gaza.

Saturday, 25 January

For the first time since last May, I saw Deir al-Balah empty and devoid of displaced people. For months there were tents in every corner, the crowded streets resembling a busy marketplace.

People began heading to Tibbet al-Tanouri, the point where they would start walking toward the north via Rashid Street along the coast. Transportation by vehicles was only allowed along Salah al-Din Street, Gaza’s central north-south road.

Everyone was carrying as much as they could – mattresses, clothes, water. Many left half of their belongings behind because they couldn’t carry everything.

My family of eight – including my parents and my five younger siblings – reached Tibbet al-Tanouri on Saturday afternoon and sat there waiting until 8:00 am on Sunday – the hour of return.

The weather was cold, but the feelings of joy filled the place with warmth. Everyone was sitting and talking about what they would do when they arrived, how they had dreamed of this moment every single day and how much they missed the north.

On Saturday evening, Israeli soldiers opened fire on us while we were camping and waiting for the order to return. But we stood our ground. The news quickly spread that Israel wanted the release of a specific captive, and that if she wasn’t released there would be no return for us.

Panic spread among the people; but we never left the place or gave up on our dream of returning to our land.

Sunday, 26 January

The day we had been waiting for finally came, after we spent the night in the street with thousands of people in the cold, fearing another betrayal from the occupation.

Morning arrived, but we were still waiting for the order allowing us to return.

We stayed in the street, with the number of people increasing, the congestion worsening and the fear growing that all our joy might vanish into nothing. After a long day full of fear, tension and rumors spreading among the people, we learned about the new agreement reached through mediators and that the return of the displaced would begin the next day.

Monday, 27 January

The morning of our celebration arrived – the celebration of returning to the north. The day we had dreamed of for more than a year.

We started walking, joy visible on everyone’s faces, as if they had forgotten the war and everything they had lived through. The chants of “Allahu akbar” (God is great) and “La ilaha illa Allah” (There is no god but God) echoed, and Palestinian flags were raised high. We were going back to the place where we were born and lived all our days. We were going back home.

This scene reminded me of the displacement in October 2023 but our emotions were completely the opposite. Back then, we were fleeing into the unknown, filled with fear and terror. Now, we were returning home.

I knew there was no home with four walls to return to. But the idea of going back to the place where I had lived my whole life, where I had spent all my days before the war, was very comforting. Now that the day I had been thinking about for 15 months had actually arrived, I finally felt at peace.

Our neighbors during displacement, the Sabah family, had their own story.

Khaled Sabah, a man in his 40s, said, “I left my family in the south and went ahead of them to our destroyed house in Jabaliya to retrieve the bodies of my three daughters – Iman, Nour and Suad – so that their mother and the rest of the family wouldn’t have to relive those emotions or see that scene again. Now, I am on my way north.”

Another displaced person, Iman al-Madhoun from Beit Lahiya, whom I met along the way, pleaded for help: “I have five children and two of them can’t walk. I beg anyone to help me and take me back to Gaza.” No one hesitated to help her. We looked for a cart to carry the two children.

The road was long, but we didn’t feel its length. Paramedics in ambulances were present to treat those who fainted from exhaustion. Many people stopped midway because their children couldn’t complete the journey.

On Rashid Street, near the Netzarim junction, we found the decomposed body of a martyr. No one had been able to retrieve the body due to the lengthy Israeli military presence in the area.

After long hours of walking, we finally arrived at Jabaliya at around 8:00 pm. My feet were swollen from walking, but just arriving at the streets where I grew up made me forget all the exhaustion.

Despite the darkness, I recognized the place. I reached our neighborhood and prostrated in joy. I kissed the ground as soon as I arrived.

Our house was destroyed, having been demolished at the beginning of the war. But at that moment nothing mattered – except that we were back on our land. We set up a tent on the rubble.

The feeling was amazing, as though I had been away from my neighborhood, my home, and the streets of my childhood for so many years. This was the place that had witnessed every stage of my life until now.

The longing was overwhelming – I missed the streets, the alleyways, the neighbors. I missed walking through these places and just being there.

I had finally returned home.

Moaaz Redwan is a student at Al-Aqsa University who grew up in Jabaliya refugee camp.

Trump Goes All-In On Stealing Gaza For His Zionist Owners

By Caitlin Johnstone, reposted from Caitlin’s Newsletter, Feb. 4

Grinning like the cat that ate the canary, Hague fugitive Benjamin Netanyahu sat beside Donald Trump as the US president unequivocally told the press on Tuesday that the plan for Gaza is to permanently remove all Palestinians from the enclave.

“I don’t think people should be going back to Gaza,” Trump said. “I think that Gaza has been very unlucky for them. They’ve lived like hell.”

Asked for clarification on whether the Palestinians would have a right to return to Gaza after its reconstruction, Trump said the plan is to build them housing in other countries that’s so nice they won’t want to return.

“It would be my hope that we could do something really nice, really good, where they wouldn’t want to return,” Trump said, adding, “I hope that we could do something where they wouldn’t want to go back. Who would want to go back? They’ve experienced nothing but death and destruction.”

Asked how many people he was talking about removing, Trump replied, “All of them.”

BREAKING: Donald Trump plans on Ethnic Cleansing Palestine:

“All of them. Theres 1.7 or 1.8 million people. They can settle, all of them to areas where they can live a beautiful life and not be worried about dying everyday” pic.twitter.com/Sy8y7p0oIO

— Sulaiman Ahmed (@ShaykhSulaiman) February 4, 2025

Shortly thereafter, the president announced that the US would soon “take over” and “own” Gaza and oversee construction projects there.

“The US will take over the Gaza Strip, and we will do a job with it, too,” Trump said. “We’ll own it and be responsible for dismantling all of the dangerous unexploded bombs and other weapons on the site, level the site and get rid of the destroyed buildings — level it out. Create an economic development that will supply unlimited numbers of jobs and housing for the people of the area.”

Given what Trump previously said about permanently removing all Palestinians from Gaza, there is no question who he is talking about when he says he wants to provide housing for “the people of the area”. He obviously isn’t talking about creating housing for the Palestinians of Gaza, so he presumably means housing for Israeli Jews. He’s talking about a very straightforward ethnic cleansing operation, driven by the United States.

Trump clarified that when he said the US would “own” the Gaza Strip, he did not misspeak. “Everybody I’ve spoken to loves the idea of the United States owning that piece of land,” he told the press.

BREAKING: Donald Trump plans on Ethnic Cleansing Palestine:

“All of them. Theres 1.7 or 1.8 million people. They can settle, all of them to areas where they can live a beautiful life and not be worried about dying everyday” pic.twitter.com/Sy8y7p0oIO

— Sulaiman Ahmed (@ShaykhSulaiman) February 4, 2025

Trump reiterated his previously stated position that the people of Gaza could be relocated to Jordan or Egypt or “other countries”. Of course the possibility of Palestinians living anywhere else in their historic homeland has not been mentioned, because that’s not how ethnic cleansing works. The agenda is to remove an undesirable population from the land so that they can be replaced with a desirable one; allowing Palestinians from Gaza to live in Israeli territory or the West Bank during reconstruction would defeat the purpose of Israel’s actions since October 2023.

Trump repeatedly spoke of how devastated, dangerous and uninhabitable Gaza is, making it sound like the area was hit by an unfortunate natural disaster and not a deliberate and methodical operation to make the enclave unlivable. This ethnic cleansing plan is being presented as a humanitarian solution to tragic circumstances, when in reality the US and Israel destroyed Gaza on purpose with the goal of advancing the exact agenda they are working to advance today.

This move is sure to be aggressively resisted, both internally by Hamas and by neighboring powers, even if the Trump administration can find nations willing to facilitate its ethnic cleansing plans. This means we can expect significantly more violence and killing in the region if this agenda moves forward.

And it should here be mentioned that Donald Trump has publicly admitted to being bought and owned by Zionist oligarchs. The president openly acknowledged on the campaign trail that the first time he was president, megadonors Sheldon and Miriam Adelson were at the White House “probably almost more than anybody” demanding favors for Israel like moving the US embassy to Jerusalem and acknowledging Israel’s illegitimate claim to the Golan Heights, which he eagerly granted. Miriam Adelson, who is Israeli-American, gave the Trump campaign $100 million last year.

And that’s the price of entry if you want to become president of the United States. You have to make alliances with oligarchs and empire managers who want very ugly things for our world, and you have to be the sort of person who is sufficiently dead inside to make such Faustian bargains. That’s why US presidents are so consistently evil; if they weren’t, they’d never make it anywhere near the presidency.

Impractical, Incomprehensible, Illegal: Trump Traps Netanyahu and Sows Chaos With U.S. Takeover Plan for Gaza

Trump’s plan for the Gaza Strip that includes the relocation of 2 million Palestinians is not logical or viable. Whether it’s an imperialist tantrum or an actual ‘out of the box’ initiative, there is really no way to endorse, refute or examine it

By Alon Pinkus, reposted from Ha’aretz, Feb. 5

You have to admire the noble attempts to instantly try and make sense of something U.S. President Donald Trump says one day, only to furiously rebuke and deride him the next. Oh wow, the sheer creativity and sublime “out of the box” innovation of proposing to relocate over 2 million Gazans and then “take over Gaza.” Genius.

Makes sense, right? Of course it does, because Gaza truly is uninhabitable.

[Editor’s note: many Gazans disagree.]

Oh no, but it’s not practical or viable. In fact, it’s incomprehensible.

So what does Trump want? Distraction. He thrives in the chaos and constant distractions he creates. Did he not impose 25 percent tariffs on Canada and Mexico, and then grant them a 30-day extension since they promised they would do the things they are already doing?

Trump is a preeminent agent of chaos. That’s a trademark he has always paraded, boastfully and defiantly. As he said he would, he is actively generating and promoting chaos in America, discord within alliances, and is out to undermine the world order.

Agents of chaos sow chaos. It’s that simple. They instill discordance, confusion, controversy and uncertainty. That’s a modus operandi, not a tailored policy or crisis management technique. Agents of chaos and anarchy are by definition out to disrupt the status quo by floating outrageous ideas, based on a simple principle: Everyone viscerally understands the status quo has exhausted its usefulness, more-of-the-same doesn’t work anymore.

As for the Israeli-Palestinian issue, the endless, irrelevant and incoherent mumbling about “the two-state solution” is just an exercise in futility. Trump only said what many are thinking, right?

Yet still, you might have missed three critical points in Tuesday’s reality TV sitcom in the East Room of the White House. First, until the United States “takes over Gaza,” the cease-fire and stage two of the hostage release agreement need to continue – otherwise how will the Americans take over Gaza?

Second, the United States is applying “maximum pressure” on Iran to compel it to engage in a new nuclear deal. So, no U.S. war in Iran for the time being.

Third, what happened to the “Saudi-Israeli normalization” process?

After Trump returned to power, initially it was all about annexing Canada and turning it into the 51st state. Then came the renaming of the Gulf of Mexico to the Gulf of America. Then came the audacious proposal to purchase Greenland from Denmark – and now the United States wants to take over Gaza and turn it into a Riviera.

Who is Mar-a-Gaza for?

That’s not a bad harvest for two weeks by the “America First” president of a superpower that has always prided itself on being “a reluctant empire.” Are these imperialist tantrums, common-sense truisms aimed at provoking and stirring emotions, a coherent plan? Or are they just outlandish and left-field comments with a life expectancy of several days at best? It could very well be all of the above.

The realtor-in-chief came up with an amazingly simple idea: empty the Gaza Strip so that reconstruction can begin. This real-estate development process evolved throughout Tuesday. First Trump called it a “demolition site,” repeating things he said a few days earlier about how the devastated-to-rubble Strip was uninhabitable. Then his aides said Gaza effectively required 15 years and billions of dollars for reconstruction, so the Palestinians would have no alternative but to move out. That makes sense when you come from real estate.

By noon, Gaza was a “hellhole,” which means that 2 million Palestinians must quickly move to Egypt and Jordan – who, according to Trump, will agree to accept them.

By late afternoon in the White House, Trump was proclaiming that America will take over and turn Gaza into “the Riviera of the Middle East.” But if the Palestinians are relocated, who will this Mar-a-Gaza be built for? Ah, that’s easy according to Trump: “Palestinians, mostly,” though it would also be “an international, unbelievable place.” So maybe Greenlanders fed up with the cold, or Canadians who want an NHL expansion team in Rafah.

[Editor’s note: extremist Israeli politicians like Israeli Minister of National Security Itamar Ben Gvir, Minister of Finance Bezalel Smotrich, and settler organizations like Nachala have their eye on Gaza for Jewish settlement.]

Even if you’re not instinctively dismissive of or resistant to Trump’s idea, the total lack of details and specificity make it impossible to endorse or repudiate.

There is no reference to legal matters: By what power and authority can the United States take over Gaza? Logistics: How do you relocate 2 million people, most of whom may not want to leave? Political: Who will manage this process? Financial: Who will fund this monumental undertaking? Regional: Most Arab countries have already vehemently rejected the idea.

Beyond the intuitive inclination to deride the concept, there is really no way to endorse, refute or examine its feasibility. So here’s the bottom line: Do not try to find logic, coherence or patterns. Just wait a few weeks. It may all change.

What Netanyahu didn’t get

Throughout his career, Benjamin Netanyahu always followed the sage advice of Yogi Berra: “When you come to a fork in the road, take it.” Years of solipsism, manipulation, deceit, duplicity, confabulation, interpolation and retraction, all woven into a modus operandi that provided him with success.

The indecision-maker would always come up with a speech, delivered with a tormented face and melodramatic baritone, describing the excruciating dilemmas he faced before making no decision. But not making a decision is a decision in and of itself, and he was good at it. Now Trump, for better or worse, is making decisions for him.

Netanyahu’s jig is up. He was nothing more than a prop in the Trump White House show. Trump upended the playing field on Gaza, Iran and everything else. It may not be sustainable, but as of today Netanyahu has to play by Trump’s rules.

Before going to Washington and after his meeting with Trump, he was presented with a fork in the road, a binary choice: desert the hostages, resume a goalless war and save his government in the immediate time frame. Or adhere to the cease-fire agreement he signed, move on to stage two and risk losing his ruling coalition.

Sometimes, making contradictory promises and giving inconsistent assurances is impossible to square. Now Netanyahu will try to market a mirage, according to which he was in on Trump’s plans. Maybe he was.

How does that change the future of Israeli-Palestinian relations? It doesn’t. Can he now annex the West Bank? He cannot. Does it add stability and predictability to relations with the United States? It doesn’t.

So what did Netanyahu get out of his Washington trip? A few days reprieve for his coalition, during which he can persuade them that Trump proved he’ll allow Israel to resume the war. And did Trump do that? No.

The Geographic and Demographic Imperatives of the Palestinian Refugees’ Return

It is feasible to repatriate a large number, if not all, of the Palestinians in the ‘shatat’, i.e. exile, to their original places of residence and rebuild Palestine into one country [About 80 percent of Gazans are exiles from what is now Israel.]

If Gaza refugees return, they can literally walk to where their homes were within an hour.

Much of the land is sparsely populated, with only marginal agricultural output, and is not of any particular vital socio-economic importance to the large settled Israeli population elsewhere. The real reason for holding to it is to prevent the return of the land owners to their homes.

Housing for the returning Palestinians is also not a problem. The author researched this matter and found that the destroyed homes, less than one million housing units, can be rebuilt entirely by Palestinians…

A report attributed to the CIA21 estimates that in the next 15 years, two million Israelis, including half a million who currently hold US green cards or passports will move to the United States, and 1.6 million Israelis would return to Russia and Eastern Europe. It is of interest to note that in any calendar year, about three quarters of the Israelis travel outside the county…

By Professor Salman Abu-Sitta, reposted from Palestine Land Society, 2013

Diplomats, politicians and activists alike have long laboured under the assumption that a two-state solution is the only path to peace between the Israelis and the Palestinians. But as this goal has not come to fruition, and the ever-elusive scepter of peace slips further from reach, violence and instability deepen. This book discusses another–until recently unthinkable-option: a single bi-national state in Israel-Palestine, with all inhabitants sharing in equal rights and citizenship, regardless of ethnicity or faith. It is the first rigorous exploration of this innovative and controversial alternative that has entered the discourse surrounding the peace process. With scholars from both sides of the conflict analysing the possibility of a one-state solution and the shortcomings of the two-state track, this is an important and ground-breaking book for students of Politics, International Relations, Peace Studies and Middle East Studies and all interested in the resolution of this intractable conflict. Contributors include Salman Abu Sitta, Omar Barghouti, Nadia Hijab, Gharda Karmi, Ilan Pappe, Gabriel Piterberg, Virginia Tilley and Husam Zomlot.

Chapter Eleven

The history of the Zionist-Palestinian conflict is full of landmarks. To name a few, the 1897 founding in Basle, Switzerland, of the World Zionist organization which set the stage for the ongoing conflict, the 1948 declaration of the establishment of Israel in Palestine, and the war of June 1967 which resulted in the Israeli occupation of the whole of Palestine. Common to the history of the conflict is the planned, and still continuous, ethnic cleansing operation against the indigenous population of the land.

There is a sense of permanence in all of this. During the long period of the conflict, Zionism had three objectives which are still very much in force, namely; occupying and acquiring Palestinian land, expelling its inhabitants, and erasing their history, memory and identity.1 To achieve these objectives, Zionists needed to manufacture and propagate a myriad of myths such as: Palestine is a land without people; there is no such thing as Palestinians, they do not exist; the Palestinians left their homes and country in 1948 on Arab governments’ orders; refugees may not return to their ancestral villages which no longer exist and their former sites have been built over and so on.2

In spite of all, the Palestinians are still here, growing and resisting. They are a prime player in Middle East events. Strangely enough, a weird stalemate between the might of a colonial power and a defenseless people exists and the outcome is open to a myriad of possibilities since it is a changing and dynamic situation. Meanwhile, the machine of death and destruction will continue to wreak havoc on both sides, however disproportionately, until a settlement is reached. Will and should such a situation be allowed to continue? The answer is emphatically no. To achieve this end, a form of durable justice must be attained.

There are a number of geographic, demographic, political and military factors which hinder the application of an equitable solution to the conflict. It is the position of this author that all these factors are manageable except one; namely, the dominance of the ideology and practice of Zionism and its associated policies of racism and apartheid. Although this is central, this essay does not attend to this issue. Instead, it concentrates on the geographic and demographic factors to show whether they could serve the cause of justice or not. Although the problems associated with those factors are of a second tier nature, they indicate once more that Zionism is the primary obstacle to achieving peace and justice and bringing an end to this chronic conflict.

The thesis this essay presents has not been examined in depth by any other scholar so far. Though the factual data that form its basis have been published by the author before, they remain unchallenged by other scholars. The essay proposes to demonstrate that it is feasible to repatriate a large number, if not all, of the Palestinians in the ‘shatat’, i.e. exile, to their original places of residence and rebuild Palestine into one country. Any resulting dislocations will be manageable. To substantiate this thesis, three elements need to be considered and defined clearly; namely, the land of Palestine, the people of Palestine and the law of the land.

The Land

Palestine is a well documented country. The Byzantines had a detailed inventory of Palestinian villages in the 4th century. The Ottomans had detailed books of taxation and census since 1596. The British Mandate produced, in its short term of 30 years, voluminous data on Palestinian land and people that became the basis of United Nations records.

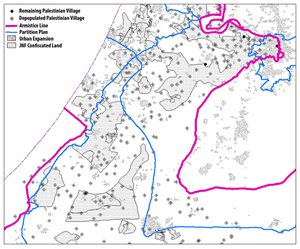

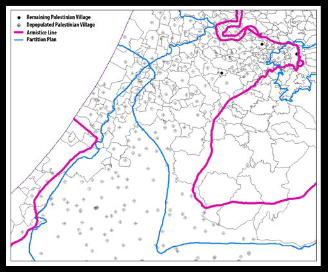

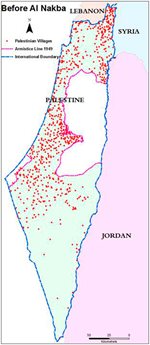

British records show that, at the end of the Mandate, Jewish ownership in Palestine reached 1,429 square kilometers out of Palestine’s area of 26,322 square kilometers. Thus, Jewish ownership was 5.4% of the area of Palestine, in spite of British collusion during the Mandate.3 But this small percentage was dwarfed during the war of 1948/1949 when, in a matter of a few months, Zionist forces captured 78% of Palestine. Palestinians refer to this development as ‘al-nakbah’ or catastrophe.4 The Palestinian lands conquered in 1948 are shown in [Fig-1]. It is important to recall that half of the refugees were expelled by Zionist forces before Israel was declared on 14 May 1948, before the British Mandate ended and before any Arab regular soldier set foot on Palestinian soil in order to assist its people.

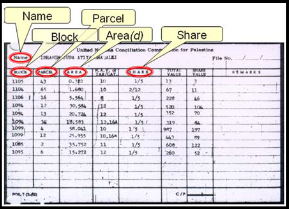

Eighty-five percent of Palestinian inhabitants of the land that is called Israel became refugees, and remained ever since. There is at the UN 453,000 records of individual Palestinian property owners defined by name, location and area, [Fig-2].5 Given the detailed knowledge that exists of almost every parcel of land in Palestine, it is feasible to investigate what the Israelis did with the conquered Palestinian land.

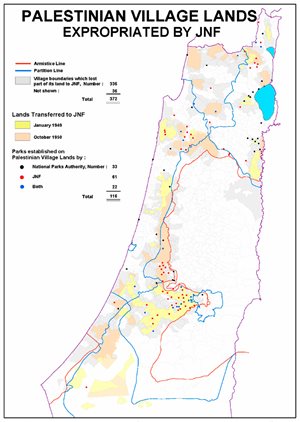

In one of the curious twists of history, Ben Gurion anticipated there will be an international demand on Israel to restore conquered lands and property to its legal owners. To subvert such a possibility, Ben Gurion, then leader of the Provisional Government, and the Zionist command, fine tuned a plan to prevent the return of Palestinian refugees to their homes and property which was later demanded by UN Resolution-194 of the 11PthP of December 1948. He ordered the demolition of several hundred Palestinian towns and villages and entered into a fraudulent deal with the Jewish National Fund (JNF), an international Jewish organization registered as a tax-exempt charity in the USA and Europe. The deal was a fictitious sale contract of choice Palestinian land adjacent to the armistice line in order to prevent the return of the refugees. This way, he would claim that this land was not under his control. The data for this fictitious deal is shown in [Fig-3]. JNF had expropriated most of the property of 372 villages on which it established 116 parks under the slogan clean environment.6 JNF planted parks in order to hide the rubble of destroyed Palestinian homes and the cactus plants which refuse to disappear till this day.

All the land acquired by the JNF during the Mandate and the Palestinian land seized by Israel is administered by the Israel Land Administration (ILA).7 The area under ILA varies according to various acts of expropriation but it ranges from 18,775 to 19,508 square kilometers.8 In order to examine the possibility of reconstructing Palestine after the destruction of its landscape and seizure of its land, consider the region bounded by Jaffa-Tel Aviv-Jerusalem corridor in the north, and Gaza in the south. This corridor was subject to great changes in the last sixty years due to rapid urban expansion and the concentration of the population in this area. The selected region envelops the southern portions of Tel Aviv, Central Israel and the inhabited upper Israeli Southern District according to the current administrative division in Israel. Other areas are less problematic.

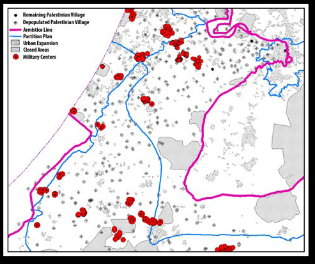

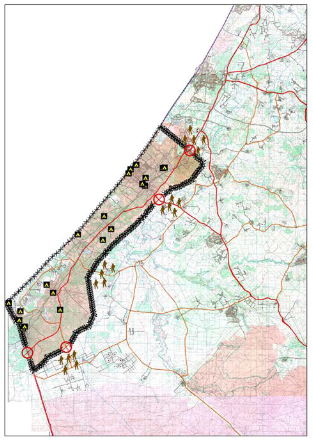

[Fig-4] shows this region with its mostly Palestinian villages and their land area before 1948. All these villages, except 2, were ethnically cleansed by the Israelis in 1948. The population was expelled south towards the Gaza Strip and east towards the West Bank and Jordan. Their land was seized and used to expand urban development radiating from Tel Aviv to accommodate new immigrants. [Fig-5] shows the same region with the present Israeli urban expansion. It is very clear that most sites of depopulated villages are still vacant, contrary to frequent Israeli claims. The same figure shows the land confiscated by JNF. The land is allocated to some Kibbutzim in the area. As shown in [Fig-15], the total rural population in the upper Southern District, which comprises the larger area of the selected region, is smaller than the population of one refugee camp in the Gaza Strip.9This vast area of land, sparsely populated, with only marginal agricultural output, is not of any particular vital socio-economic importance to the large settled Israeli population elsewhere. The real reason for holding to it is to prevent the return of the land owners to their homes and to have it as a strategic reserve for the future. This reserve is now used to house and maintain Israel’s war machine which is constantly expanding. The attempt to populate the Southern District with new immigrants has achieved limited success in spite of the strenuous efforts of the JNF. [Fig-6] shows the same region with some of the military and strategic locations and closed areas containing military bases, factories, training grounds, missile bases and WMD depots. The density of these sites is unparalleled by any other country. Their disappearance will no doubt serve the cause of peace.

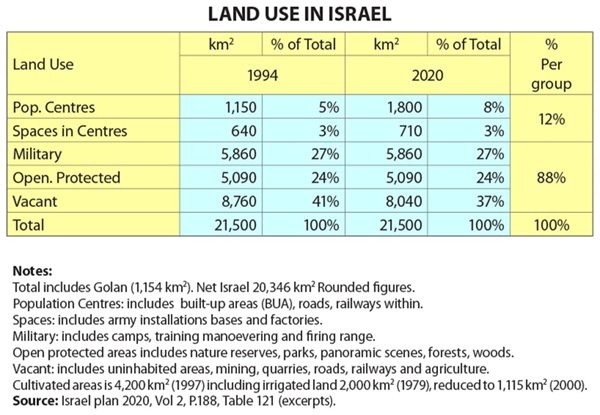

The illustrations in figures 4, 5 and 6 sums up the original cause of the problem, the reason for the continuation of the conflict and the possible ways to end it. This analysis of land use is not a mere conjecture. Israeli records confirm the indicated land use in Israel in 1994 and as projected in 2020 [Fig-7].10 It shows that most of the population lives on 12% of the Israeli land area, while 88% is used as a reserve land for the military, or protected, or closed areas, or vacant land. This includes 4,200 square kilometers of cultivated land, which uses a colossal 70%-80% of the overall water consumption, while producing only 1.5% of Israel’s GDP.11

-

Fig-4: Southern Villages Ethnically cleansed villages and their land boundaries. Source: Salman Abu Sitta, Mechanics of Expulsion: The Perpetual Ethnic Cleansing. Lecture at SOAS London, 15 January 2011, available at: click here. Adapted from Fig-19 A-E. -

Fig-5: Urban Expansion and JNF Confiscation Same as Fig-4 showing that village sites are still vacant in spite of Israeli urban expansion. The figure shows JNF-confiscated Palestinian lands. Source: Salman Abu Sitta, Mechanics of Expulsion: The Perpetual Ethnic Cleansing. Lecture at SOAS London, 15 January 2011, available at: click here. Adapted from Fig-19 A-E. -

Fig-6: Military Use of the RegionSame as Fig-4 showing that Palestinian land is used primarily for military purposes. Source: Salman Abu Sitta, Mechanics of Expulsion: The Perpetual Ethnic Cleansing. Lecture at SOAS London, 15 January 2011, available at: click here. Adapted from Fig-19 A-E.

The People

The second element in the reconstruction of Palestine as one country is people. Today, there are about 11 million Palestinians who are living in the ‘shatat’ or in historic Palestine. Pitted against them are 5.5 million Jews12 who are mainly immigrants from or after the British Mandate period, including West Bank settlers, but now citizens of Israel. How did this come about?

-

Fig-8: At home 1300 Palestinian villages in all of Palestine. Only 99 remained in the part of Palestine that became Israel. Others in that part were ethnically cleansed. Source: Salman Abu Sitta, Atlas of Palestine 1917-1966. London: Palestine Land Society, 2010, p. 122. -

Fig-9: In Exile They were scattered in over 200 locations of refugee camps, not allowed to return home. Source: Salman Abu Sitta, Atlas of Palestine 1917-1966. London: Palestine Land Society, 2010, p. 122. -

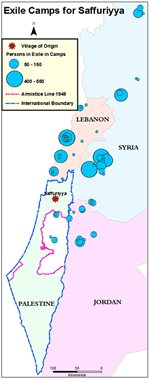

Fig-10: Saffouria Exile Those expelled from Saffouria village in Galilee sought refuge in adjacent regions, mostly Syria and Lebanon. Source: Salman Abu Sitta, Mapping Palestine: for its Survival or Destruction? Lecture at Palestine Canter, Jerusalem Fund, Washington DC, 28 April 2011, available at: click here. Adapted from Fig-19C. -

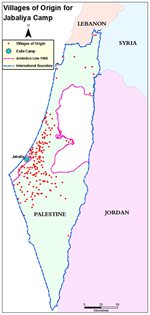

Fig-11: Villages of Origin for Jabaliya Camp Jabaliya camp pulverized by Israeli tanks and planes is the temporary home of tens of ethnically cleansed southern villages. Source: Salman Abu Sitta, Atlas of Palestine 1917-1966. London: Palestine Land Society, 2010, p. 149.

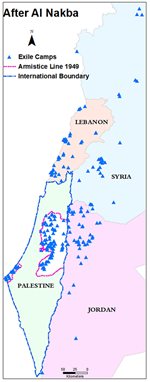

Before al-Nakbah, there were 1304 ‘villages’ in Palestine of which 956 came under Israeli rule13 [Fig-8]. Of these, 773 were Palestinian Arab villages. Israeli ethnic cleansing depopulated the majority, i.e. 674, with only 99 villages evading depopulation. The inhabitants of depopulated villages were exiled into 602 locations, registered and served by UNRWA [Fig-9]. Non-registered refugees live in various Arab and foreign countries. For registered refugees, UNRWA records show who they are, where they are from originally in Palestine and where they were exiled to.14 As an example, take the case of Saffouria, a village in Galilee [Fig-10]. Some inhabitants found refuge in nearby Nazareth. The majority were expelled to Lebanon, Syria, Jordan and the West Bank. Given that they and their descendants are known, it is possible to reconstruct their return from exile camps to their villages of origin. In other words, the process of ethnic cleansing that took place can be reversed with high reliability. Another case is that of Jabalyia Camp in Gaza which was pulverized by F16s and Israeli tanks in the December 2008 to January 2009 Israeli assault. The original villages of those people who took refuge in Jabalyia Camp, their ‘hamulas’ (extended families), even their individual names, are known, [Fig-11]. But Gaza has a special significance. Two hundred and forty seven villages in the Southern District of Mandate Palestine, i.e. Gaza and Beersheba sub-districts, were depopulated and their inhabitants expelled to the tiny Gaza Strip, [Fig-12]. They are huddled in 8 camps in a strip which is 1% of the area of Palestine, besieged from land, sea and air, and subjected to extreme deprivation. The adjacent Israeli town of Sderot, which is frequently in the news, is built on the land of Najd village whose people are now refugees in Gaza, two kilometers away. Today, 1.5 million people live in this most crowded place on earth. Not only were they expelled in 1948, but they have been attacked constantly in their exile ever since.

From a logistical point of view, the restoration of the Palestinian refugees to their land is possible as illustrated above. They are very close to their homes. Their numbers are manageable. In general, their return can be effected in 7 phases;15 each phase involving about half a million people. In Galilee, they can return to their villages without the need to efface exiting construction or uprooting the present inhabitants. An examination of the origin and distribution of the present occupants is in order. They can be classified into five categories:

- Palestinians who managed to remain at home.

- Ashkenazim who conquered the country in 1948.

- Jews from Arab countries who were brought in the 1950’s to fill the void after the expulsion of the Palestinians.

- Russians who immigrated en masse for about 5 years starting in 1989 after the demise of the Soviet Union.

- Assorted European and American Jews who came intermittently, particularly after the 1967 occupation of the West Bank, Gaza and the Golan.

This broad classification shows approximately who is filling the places from which Palestinians were expelled. It is based on the author’s research of immigration to Israel over the years,16 and on the geographical distribution and placement of these immigrants. This research covered over a thousand now–Israeli towns and villages. Of these, the findings indicate that less than 50 have a sizeable population. The rest are small settlements: kibbutzim and Moshavim, each with an average population of 300-500 people. At the same time, the author studied the Palestinian population of 674 ethnically-cleansed towns and villages. Their home villages and their exile camps were traced using the records of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA).17 Based on the voluminous data collected, it was possible to chart a plan of return.

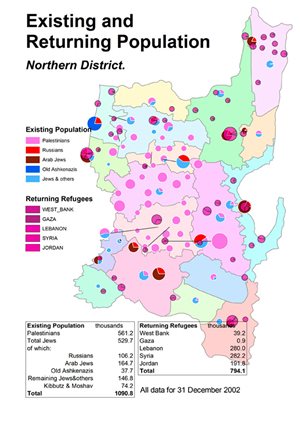

In the present Israeli Northern District, a sizeable percentage of the population is still Palestinian. [Fig-13] shows both the present population and the returning Palestinians. There does not seem to be a problem of over lapping or crowding. Refugees can take a bus and return to live in their homes with their kith and kin. It is a matter of conjecture to forecast how many Jews would wish to remain in a democratic, non-exclusive country. Similarly, it is not certain how many Palestinians would wish to return or remain where they are. In either case, Jews must have the choice and the Palestinians must be able to exercise their inalienable Right of Return.

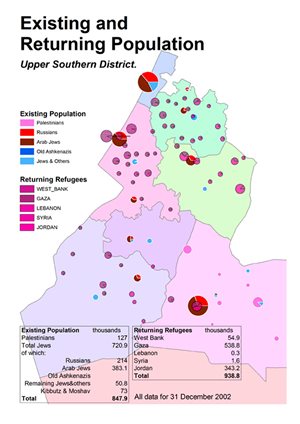

The same exercise can be applied to the present Israeli Southern District, which is actually much less of a problem. [Fig-14] shows the existing population classified as in the Northern District. With the exception of 3 originally Palestinian towns, now inhabited and expanded by Israeli Jews, all the rural Jews in this area (73,000) hardly fill one refugee camp in Gaza. The existing population and the returning refugees are almost the same number, 800,000 each. If Gaza refugees return, they can literally walk to where their homes were within an hour. Housing for the returning Palestinians is also not a problem. The author researched this matter and found that the destroyed homes, less than one million housing units, can be rebuilt entirely by Palestinians. 18 Similar or larger projects were built in the Gulf where Palestinian engineers played a key role. It is evident, therefore, that from the physical and logistical points of view, the whole process of repatriation and rehabilitation is quite manageable.

-

Fig-13: Northern District The return of the expelled population of Galilee will be welcomed by their families who remained at home. Source: Salman Abu Sitta, Atlas of Palestine 1917-1966.London: Palestine Land Society, 2010, p. 150. -

Fig-14: Southern District Total ethnic cleansing of the south left the south almost empty till today. Expelled Gaza refugees can literally walk home. Source: Salman Abu Sitta, Atlas of Palestine 1917-1966.London: Palestine Land Society, 2010, p. 150.

As far as the Jewish population of Israel, their origin, date of immigration and numbers are well documented by Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS).19 According to Ian Lustic who analyzed CBS data from 1998-2000, CBS figures show an average of approximately 13,000 annual Israel emigrants leaving the country. The average for the 4 years after the outbreak of the 2000 Al-Aqsa Intifada showed an increase of nearly 40% to 18,400 emigrants per year. According to Lustic, “A similar 40% increase in the number of Israeli immigrants gaining permanent residency or citizenship in the US, Canada, and UK was registered between the 5 years prior to the outbreak of the Al-Aqsa Intifada and the 5 subsequent years. That is a jump from 25,276 in the years 1996-2000 to 35,372 in the years 2001-2005”.20 A report attributed to the CIA21 estimates that in the next 15 years, two million Israelis, including half a million who currently hold US green cards or passports will move to the United States, and 1.6 million Israelis would return to Russia and Eastern Europe. It is of interest to note that at any calendar year, about three quarters of the Israelis travel outside the county.22 These of course are estimates which could be wildly out of line, but the important point is that most Israeli Jews have or had a passport, citizenship and likely a home outside Israel, while the majority of Palestinians do not have that option and do not wish to have it. Also, the Jewish population in Israel is fluctuating, variable and not always predictable. On the other hand, the Palestinian population is defined, stable and steadily growing.

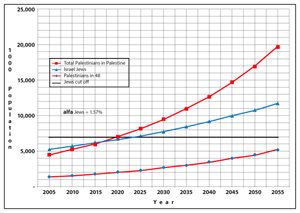

There is a prevalent racist attitude in Israel that calls the presence and growth of Palestinians in the country “a demographic bomb”.23 Such is the nature of Zionist ideology which is on a collision course with human rights. Short of a holocaust to annihilate the Palestinians, it is a futile objective. [Fig-15] shows the Palestinian and Jewish population projection in Palestine. It shows the Jewish and Palestinian citizens of Israel as having a natural growth of 1.57% until the year 2055. The top line shows total Palestinians living in the three regions, i.e. Israel, West Bank and Gaza, which form historic Palestine. The Palestinians in exile (not shown) who reside outside the borders of Palestine are approximately the same number. Anywhere between 2015 and 2017, Palestinians in all of Palestine will be equal to Israeli Jews. If a strict definition of a “Jew” is applied, the Palestinians are probably already equal in numbers to Israeli Jews. In the year 2050, Palestinians will be around 17 million and Israeli Jews will be 11 million if the present trend continues without interruption. But this is not the point.

The number of Jews in the world is almost constant at 13 million because of mixed marriages and assimilation. Israeli policy seems to have resigned itself to American and Western European Jewry not wanting to immigrate to Israel and may even be amenable to them remaining in their countries of residence since their presence there is considered strategically beneficial to Israel.24 This explains why Israeli planners concentrate on attracting Jews of Eastern Europe, Russia, Africa and Asia to move to Israel. That means there is a limited reservoir among World Jewry of potential residents or immigrants to Israel, shown in the thick horizontal black line. Accordingly, the Palestinians will undoubtedly be the majority in the future and/or in certain regions of Palestine. The uncertainly is only where and when. That is the reason for the new Israeli demand that Israel be recognized by Palestinians as a “Jewish state”. This is contrary to the Israeli declaration of independence itself which relies for its legitimacy on the 1947 U.N. Partition Plan which never envisaged a purely ethnic or religious state, nor could it ever do so. The slogan “Jewish state” is therefore meant to deny the right of refugees to return to their homes and to provide a license for Israel to expel its own Palestinian citizens as and when it deems it appropriate.25

The Law

The third element in reconstructing Palestine, next to land and people, is the law that needs to prevail in the country and the mechanism by which it is applied.26 For Palestine, international bodies and organizations, particularly the United Nations, have been involved in the issue for some ninety years. Their legal foundations and their policies and decisions can guide future actions. In them, the bases for establishing a democratic free government can be found in Article-22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Right to Self Determination. Though far from being optimal, UN Resolution-181 partitioning Palestine has some useful and necessary provisions to protect the political, civil, religious and educational rights of each group, whether Palestinian or Jewish. This should be a good basis from which an expanded formula can be developed for one country. Upholding UN Resolution-194 which has been affirmed by the international community over 135 times in the last 60 years, more than any other resolution in UN history, is also imperative. It has 3 main elements: First, it calls for the refugees to return; second, it provides them with relief until that happens; third, and most importantly, it provides a mechanism for their repatriation and rehabilitation. This mechanism is the UN Conciliation Commission for Palestine (UNCCP).

In the Lausanne negotiations, 1949-1950, Israel managed to obstruct the refugees’ return and rendered UNCCP idle.27 The only provision of relief that survived, represented UNRWA, is still in operation. But UNCCP is still legally valid and has its offices within the UN. Its annual routine report is an indication of Israel’s contempt for international law and UN resolutions. The report says every year: “we are unable to facilitate the return of the refugees this year”.

In her writings, the noted legal scholar, Susan Akram, has outlined with much clarity the legal implications of applying the Right of Return.28 It should be clear then that a legal framework for a reconstituted Palestine is available and needs to be applied, as it was in dozens of similar cases such as Kosovo, Bosnia, Abkhazia, Uruguay, Uganda, South Africa, Iraq and Afghanistan.29 Needless to say, the real question that remains of course is whether or not the colonial powers that created the problem in the first place have the political will to enforce outstanding international resolutions and apply international legal standards of justice and equity. This can never take place unless they cease their opposition to the Palestinians’ human, political and national rights. This may be a pipe dream at the moment. Hopefully, world public opinion, which is slowly but steadily becoming less enamored by Israel’s fictional image and more empathetic to the cause of the Palestinians. Possible changes in the balance of power in the world would also improve the chances of the enforcement of human rights in Palestine. Whether this happens or not is the keystone in this equation. But the outcome depends on how much the Palestinian people remain determined to restore their rights. The past six decades indicate they have a huge reservoir of tenacity.

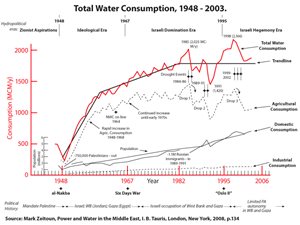

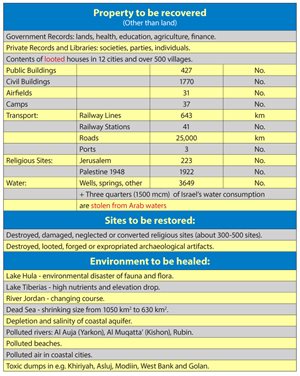

The increased consumption is due to Israel’s illegal diversion of Arab water, causing wars. Most of the consumption is used for agriculture with little economic return. Its purpose is to keep refugees’ land under Israel’s control to prevent their return. Source: Mark Zeitoun, Power and Water in the Middle East, I. B. Tauris, London, New York, 2008, p.134. When rights are restored and apartheid abolished, there is of course a lot of preparatory work to do. Sixty years of wars, occupation, war crimes, destruction and suffering cannot be wiped out easily. However, the history of Palestine has always been noted for its spirit of tolerance and absorption of diverse communities. The first task is to clean up Palestine. We have to restore Palestine, which is now concreted, polluted and ravaged, to normal life, [Fig-16]. Private and public property of Palestinians should be recovered. In particular, the important resource of water which is now wasted on cash crops and produces only 1.5% of Israel’s GDP must be restored to proper use.

[Fig-17] shows that two thirds of Israel’s water consumption was diverted from Arab sources.30 Water problems in the region emanate from misallocation and misuse, not necessarily from scarcity. Religious, archaeological and cultural Arab and Islamic sites should be restored or repaired.31 Wherever possible, the landscape has to be restored to its former pristine condition. Also, land, air and water, which have been greatly polluted by the mad rush to build, must be cleaned up.32 Palestine can provide a clean environment and a livable country for millions of people.

Footnotes (↵ returns to text)

-

See, for example, the works of Nur Masalha. The Politics of Denial: Israel and the Palestinian Refugee Problem. London: Pluto, 2003; A Land without a People: Israel, Transfer and the Palestinians; Faber and Faber, London, 1997; Expulsion of the Palestinians: The Concept of Transfer in Zionist Political Thought, 1882-1948, Institute of Palestine Studies, Washington DC, 1992; Imperial Israel and the Palestinians: The Politics of Expansion. Pluto Press, London, 2000. ↵

-

The Israeli narrative still propagates these myths but they are shown to be false by a growing body of scholarship, including that of the ‘new historians’ in Israel. See, for example, Ilan Pappe. The Making of the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1947-1951. London and New York: I.B .Tauris, 1992; Simha Flapan. The Birth of Israel, Myths and Realities. London and Sydney Croom Helm, 1987; and Norman Finkelstein. Image and Reality of the Israel-Palestine Conflict. London: Verso, 1995. ↵

-

Village Statistics, Palestine Government Printer, 1945; and Survey of Palestine, prepared in December 1945 and January 1946 for the information of the Anglo-American Committee of Enquiry, reprinted by the Institute of Palestine Studies, Washington, D.C., 1991, Vol.2, Table-2, p. 566. ↵

-

For details, see Benny Morris. The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited, 1947-1949. CambridgeUniversity Press, Cambridge, 2004; and Ilan Pappe, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine. London: One World Publications, 2007. Morris maintains the Zionist view that al Nakbah was “an accident of war”. Pappe maintains that ethnic cleansing was pre-planned. For graphic details of al Nakbah, see Salman Abu-Sitta. The Atlas of Palestine 1948 London: Palestine Land Society, 2005. ↵

-

See A/AC.25/W.84 of 28 April 1964. Working Paper Prepared by the Conciliation Commission’s land expert [Frank Jarvis] on the Methods and Techniques of Identification and Valuation of Arab Refugee Immovable Property Holdings in Israel. Jarvis summarized on cards the Land Registry books and classified them by land owner. His work covered only 20% of Palestine which was duly registered under the Land Ordinance (Settlement of Title) of 1928. This Ordinance was promulgated due to strong pressure by Zionists to make full survey of land in Palestine to determine which land can be allocated to them. The Ordinance was based on the Australian Torrence method which was a unique system combining both normal survey definition of land plot boundaries and legal documentation of land ownership. It was applied from 1928 to 1947 covering mostly areas where Jews had land ownership. The rest, predominantly Arab, was defined by the Mandate as Arab or Jewish and registered accordingly on fiscal and taxation basis. The word “Public” which appeared in Village Statistics denotes common land belonging to the village and was not taxable, such as grazing, woods or rocky areas, sometimes registered under the name of the High Commissioner. This is not to be confused with State Land which was allocated for government disposal such as the granting of concessions. The latter area comprised only 1,179.8 sq km (1945). The British left in a hurry without completing the implementation of “Land Settlement” according to the 1928 Ordinance. Their hurried departure would not have caused a major legal dispute of land ownership as the Jews fully registered their land and the rest was recognized by all to be Arab owned. ↵

-

Noga Kadman Source: Noga Kadman. Erased from Space and Consciousness-Depopulated Palestinian villages in the Israeli-Zionist Discourse. Master’s thesis in Peace and Development studies, Dept of Peace and Development Research, Göteborg University, Sweden, November 2001. See also JNF Report: View PDF; and Michael R. Fischbach. Records of Dispossession: Palestinian Refugee Property and the Arab Israeli Conflict. New York: Columbia University Press, 2003, pp. 58-68. ↵

-

A series of laws were promulgated to legalize the seizure of Palestinian land and escape international censure. See for example Geremy Forman and Alexander Kedar, From Arab Land to ‘Israel Lands’: The Legal Dispossession of the Palestinian Displaced by Israel in the Wake of 1948 .Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 2004, Vol. 22, pp 809-830; Sabri Jiryis. Settlers’ Law: Seizure of Palestinian Lands. Leiden: Palestine Year book of International Law, Vol. II, 1985, pp. 17-36; Hussein Abu Hussein and Fiona McKay. Access Denied: Palestinian Rights in Israel. London: Zed Books, 2003, pp. 69-77. ↵

-

Walter Lehn and Uri Davis. The Jewish National Fund. London: Kegan Paul International, 1988. p.114. See also, Abu Hussein, op. cit, p. 135, 150. ↵

-

See Fig. 15 herein for population figures. ↵

-

Two hundred and fifty Israeli and foreign experts met over several months to examine Israel’s future by 2020. The result was 18 volumes of analysis. See, Adam Mazor. Israel Plan 2020. Haifa: The Technion, 1997. Translated into Arabic by the Centre for Arab Unity Studies, Beirut, 2004. Fig. 7 is adapted from Vol. 2, p. 188, Table-12.1. ↵

-

Salman Abu Sitta, “The Feasibility of the Right of Return” in Ghada Karmi and Eugene Cotran (eds.). The Palestinian Exodus, London: Ithaca, 1999. ↵

-

According to the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), the population of Israel in Sept 2009 was 7,465,500 of which 5,634,300 were Jews, assuming that all Russians are Jews, 1,513,200 Palestinians including those in annexed Jerusalem and 318,300 others, mostly foreign workers ↵

-

The figure of 1304 “Villages” as shown in British maps refers to all towns, primary villages, secondary villages, hamlets and Jewish colonies in Palestine during the Mandate. Of these, 956 were situated inside the Armistice Line of 1949. 183 were Jewish colonies, leaving 773 Palestinian Arab ‘villages’ under Israeli rule. Of the latter, 99 remained intact and 674 were depopulated. Other scholars quote less numbers than 674 depending on their definitions. Benny Morris refers only to 369 towns and villages. Walid Khalidi listed 418 villages and excluded towns, smaller villages, hamlets and all of Beersheba district except for 3 villages. For the names and location of the total depopulated villages of all types, see Salman Abu Sitta. The Atlas of Palestine 1948. London: Palestine Land Society, 2005. ↵

-

See, generally, click here. UNRWA Registry gives detailed information about every refugee. ↵

-

For details, see Salman Abu Sitta. From Refugees to Citizens at Home. London: Palestine Land Society, 2001. Available online at: click here; See also Salman Abu Sitta. The Return Journey (Atlas), London: Palestine Land Society, 2007. ↵

-

See Annual Statistical Abstracts, Central Bureau of Statistics, Israel. ↵

-

Registered refugees at UNRWA represent only 75% of all refugees. Others did not register in 1949-50 because registration was based on need for food and shelter which they did not require as they had their own resources. ↵

-

From Refugees to Citizens. op. cit. ↵

-

See, for example, the Tables in the Population Section for 2009 in CBS: click here ↵

-

Ian S. Lustick, “Abandoning the Iron Wall: Israel and the Middle East Muck”, Middle East Policy. Vol. XV, No.3, Fall 2008, pp 30-56. Available at: click here ↵

-

Franklin Lamb, “Fearing One-State Solution”,Dissident Voices, 19 February 2009. ↵

-

CBS Statistical Abstracts of Israel 2009 No 60, Table-4.1. In 2008, 4,206,800 Israelis were listed under “Departure” category. No figures are given for the departing immigrants or potential immigrants but they are given for those arriving. Figures for the arrival and departure of “tourists”, 2,572,300 and 2,373,600 respectively, mostly Jews, are given. view pdf ↵

-

Netanyahu expressed this view at the Herzliya Conference in December 2004. The extremist Avigdor Liebermann has publicly advocated the expulsion of Palestinian citizens of Israel. The debate about this issue is common in many sectors of the Israeli society without fear of censorship or condemnation. ↵

-

Adam Mazor. Israel Plan 2020. Haifa: Technion, Israel, 1997, Vol. 6, Projections of World Jewry under the major planning theme “Israel and World Jewry”. ↵

-

Jonathan Cook. Disappearing Palestine: Israel’s Experiments in Human Despair. London: Zed Books, 2008. See also click here, various press releases. ↵

-

For examination of the legal background, see: W.T. Mallison and S.V. Mallison. The Palestine Problem in International Law and World Order. Essex: Longman, 1986; and John Quigley. Palestine and Israel: A Challenge to Justice. Durham University Press, Durham, 1990. ↵

-

Ilan Pappe. The Making of the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1947-1951. London and New York: I.B.Tauris, 1992, p. 212. ↵

-

The reader may refer to the contribution of Susan Akram to this volume. ↵

-

For a variety of applications of property restitution in various areas of conflict, see click here. ↵

-

The figure shows how Israel’s consumption rose from 350 million cubic meters per (mcm) at its establishment to about 2000 mcm at present. This increase was provided by the diversion of Arab water. The agricultural consumption of water is erratic and produces a negligible part of GDP. Industrial consumption of water is relatively constant but domestic consumption grows with increased population. ↵

-

Many of the religious and archaeological sites were destroyed, desecrated, looted or claimed to be Jewish. See Raz Kletter. Just Past? The Making of Israeli Archaeology. London: Equinox, 2006; and Nadia Abu El-Haj. Facts on the Ground: Archaeological Practice and Territorial Self-Fashioning in Israeli Society. Chicago: The University of Chicago, 2001. ↵

-

A comprehensive survey of heavy pollution in Israel is given by Alon Tal. Pollution in a Promised Land: an Environmental History of Israel. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002. ↵

Additional information:

- A Realistic Plan of Return For Palestinians to Their Homeland | Salman Abu Sitta (video)

- The Right of Return is still the issue

- “We will rebuild our lives from scratch”

- Jared Kushner says Gaza’s ‘waterfront property could be very valuable’

- Gaza is not a “thing,” Mr. President

- What was happening in Gaza BEFORE the Hamas attack that the media didn’t tell you? (video)

- ‘It’ll Only Be Death’: Trump Says No One Should Live In Gaza After Israel-Hamas War

- Glenn Reacts to Trump’s Gaza Take Over: System Update Special (video)