Amid Gaza’s destruction, I walked alongside displaced families returning home, observing their suffering, profound loss, and indomitable strength

By Ahmed Abu Artema, Reposted from Middle East Eye

On the morning of Monday, 27 January 2025, I couldn’t help but join the hundreds of thousands of displaced Palestinians returning to their destroyed homes in northern Gaza.

I have no house there. My home, once in the south of the Gaza Strip, was destroyed. But it was the sense of defiance and a desire to be part of the collective spirit that moved me.

Before the war, traveling to Gaza City was a routine, hassle-free trip.

I commuted there for work almost daily, with the journey taking no more than half an hour. The last time I had gone was on Thursday, 5 October 2023.

But the reopening of the road, which had been closed and blocked for so long, presented new challenges.

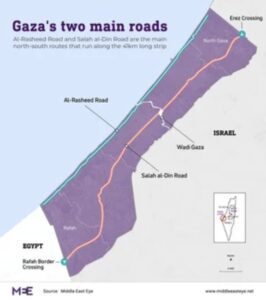

I left the Mawasi area of Khan Younis and headed towards the nearest point on Al-Rasheed Street, which leads to Gaza City. Finding transportation became another difficult challenge.

I walked for more than an hour, trying to flag down any passing vehicle, but to no avail. The number of people crowded in the streets far exceeded the capacity of any available transport.

Despite my best efforts, I couldn’t find any ride and continued on foot until I reached the outskirts of Deir al-Balah.

Makeshift transport

Caution is advised when using the term “means of transport”.

These are not the safe vehicles we once knew before the war, which has destroyed thousands of vehicles, along with everything else.

As necessity is the mother of invention, people have been forced to rehabilitate whatever could be salvaged from the wreckage.

It’s no surprise, then, to see strange metal structures roaming the streets. These are the remains of cars that were destroyed but later repaired by their owners, who replaced engines or hastily constructed metal frames to transport passengers.

You may also find a small car towing one or two carts – usually pulled by donkeys – or a motorcycle with a wooden or metal box attached to carry passengers. Alternatively, you might come across a truck, originally used for transporting goods, now holding hundreds of passengers, either inside or hanging from the sides.

Under normal circumstances, people would not have accepted such uncomfortable and dangerous means of transport. However, objecting now is a luxury, as there is simply no alternative.

After walking for over an hour and waving at anything that passed, I saw a car towing a cart. A boy riding on the car bonnet shouted, “Come and ride with us. Quick!”

Looking at the passengers crammed inside, I replied: “I can’t find any space inside.” He called back, “Come and ride next to me on the bonnet.”

It was an unusual offer. I had never ridden on a car bonnet before. Yet I quickly agreed, knowing there were no alternatives. Had I turned it down, I would have likely had to walk the entire distance.

Usually, this part of the car would be terrifying and insecure. There’s no protection, the surface is slippery, and there are no handles to cling to while the car is moving. It was never designed for people to ride on.

However, what gave me a sense of relative security was the fact that the car was moving slowly due to heavy traffic and the bulldozing of roads.

The car couldn’t go faster than a person walking. Despite the discomfort, I felt a strange joy in experiencing this new adventure – bonnet riding.

The slow pace allowed passengers and street vendors on both sides of the road to bargain without the need for vehicles to stop.

For example, a conversation took place between the boy sitting next to me and a young man walking alongside us, holding two dogs on leashes. The boy asked, “Would you sell me this small dog for a hundred dollars?” to which the young man replied, “I don’t want to sell it, not even for a thousand dollars.”

Still feeling a sense of amusement, I joined in with a tease. I asked the dog owner: “How about selling it to me for 10 shekels (about $3)?” He responded politely, “Keep your money.”

We finished the conversation and continued on our strange journey.

Endless struggles

The car reached Az-Zawayda crossroads, about 10 km from Gaza City. The traffic jam had worsened to the point where vehicles came to a complete standstill.

“The road is closed. I’ll drop you here,” the driver said. The passengers disembarked. I gathered from their argument that the driver had charged them a hefty fee to take them to a specific destination.

When he dropped them there, they demanded a discount, claiming they had not reached their intended stop. The driver insisted the road was closed, while the family argued they hadn’t been dropped off at the agreed location.

I felt sympathy for the family. I said to the driver, “You should have been upfront with the passengers from the start. You knew the road was going to be closed. Why didn’t you explain that?”

I was the least burdened of the lot. Most of the crowd was returning to their homes – or what was left of them. They carried children and belongings, while I walked alone with nothing but a small water bottle and my wallet.

It was a harrowing sight: the elderly, children, the sick, women, and men carrying their belongings, all walking slowly. The crowds stretched endlessly into the distance. Along the way, people would sit when they grew exhausted.

There was no proper road or pavement. People searched for any stone they could sit on or lay down on the sand and mud.

Witnessing devastation

Al-Rasheed Road in Sheikh Ijleen was once famously lined by vineyards. Grapes were a distinctive feature of the area, and the harvest once even reached overseas markets.

A young man walking beside me asked, “Where have all the vineyards gone?” “They’ve been bulldozed,” I replied. All that remained were ruins.

Residential towers and buildings had been leveled. The Israeli army had swept through, leaving nothing but total destruction and rubble.

The further they walked, the more exhausted the people appeared.

I saw an elderly woman lying on a blanket in the middle of the road, unable to continue. She had found no vehicle to carry her. I saw an older man carrying a gas cylinder who, in his exhaustion, threw it ahead of him and let it roll.

I saw another man who had lost a leg, relying on a wooden crutch while carrying a bag on his head as he walked with the crowds.

I saw a young woman walking alone. At the start of the war, she had been displaced with her husband and two children. But her entire family was killed in an Israeli raid in the south.

She was now returning alone to join her parents. She cried bitterly the entire way, praying to God to burn the hearts of those who had torched hers with the loss of her children and husband.

I saw thousands of women carrying heavy bags while their children clung to their garments. Exhaustion and dust covered their faces as they walked. Their eyes were wet with tears as they struggled through the rough terrain, burdened by the weight. But they had no other choice.

I saw mothers sitting along the way, breastfeeding their infants. I saw hundreds of families lying on the sand, hoping to regain some strength after a brief rest.

I saw children crying from exhaustion. I heard a mother say to her child: “Are you tired of walking, my love? I know you’re exhausted. I shall carry you.” She said this while bearing two heavy bags. Walking beside her, her husband carried four.

The long way

I saw a girl standing amid the crowds, looking around, crying, and carrying a heavy bag.

I asked her what had happened, and she explained that she had gotten separated from her family while walking. I took her bag from her and said, “I’ll walk with you until you find them.”

We walked for more than half a kilometer before she pointed ahead and said: “That’s my uncle, and next to him is my mother.”

Carrying the girl’s bag quickly exhausted me, and I kept switching it from one shoulder to the other. After just half a kilometre, I wondered how this frail young girl had managed to carry it for so long.

Indeed, compassion emerges in times of hardship.

I saw a young man carrying his father on his back as they made their way down the long road. I saw two young men supporting an elderly woman who could have been their mother or grandmother.

They walked slowly, each step heavy with fatigue. The woman showed clear signs of exhaustion. One of them said to the other, “Let her rest for a moment.”

Along the way, I heard cries for water.

Children, young girls, and men looked around, asking for any water they could find. The energy people had at the start of the day quickly faded, like a car running out of fuel. Their steps slowed, growing heavier with each one.

People began collapsing onto the ground. The road ahead seemed endless. Faces grew pale and weary from exhaustion, and I saw young girls crying helplessly.

Most of these people had never experienced such hardship before. I’m sure these women never realised they could endure such unimaginable circumstances. I saw one woman carrying two gas cylinders, each weighing six kilograms – one in her right hand and the other in her left.

The path was barren and destroyed, littered with deep potholes gouged by bulldozers. Keeping children from falling into these holes added to the many challenges of this long journey.

Aftermath and return

Al-Rasheed Street, once a symbol of Gaza’s beauty, had been destroyed and bulldozed by the Israeli army.

The Zionist media published two photographs of this street – one before the invasion and one after – gleefully celebrating the destruction. What else can be expected from a state waging war fueled by hatred, revenge and malicious satisfaction?

While moving through the area, I saw a crowd gathered around a particular spot. They had just discovered a decaying corpse or perhaps some bones.

Medical authorities expect that hundreds of decomposed bodies may still lie beneath the rubble and sand, as this route had been off-limits to medical teams during the months of war.

The return of the people might have been easier had the Israeli army allowed residents to return by vehicle or even by animal-drawn carts.

This would have spared the sick, elderly, women, and children much suffering.

Yet, Israel has pursued a policy of inflicting distress, aiming to extinguish the inherent joy of the Palestinian people. It continues to deny them even the most minor comforts, ensuring they never believe their will has triumphed over their occupiers.

Towards the end of the road, a car with loudspeakers blared national songs. Green and black flags fluttered in celebration of victory and steadfastness.

I then saw a few trucks distributing drinking water while volunteers from local charities handed out meals, congratulating the returnees on their safe arrival.

On that day, I walked as I had never walked before – about 15 km non-stop. I entered Gaza City, a dream long cherished during the days of the war, now realized.

I looked around, trying to familiarize myself with what remained of the streets and buildings. At first, I couldn’t recognize them due to the destruction. But as I ventured deeper into the city, I began to make out some familiar features.

The destruction was widespread, though not as catastrophic as in Rafah, to which I had returned a week earlier.

Whenever my gaze fell on a building that had survived, my heart swelled with joy. These surviving structures are all that remain of hope that life in Gaza has not yet come to an end.

Statistics reveal the shocking extent of the destruction, with experts predicting it will take decades to rebuild. This reality weighs heavily on our hearts, yet even in the midst of it, there is joy in witnessing that life has endured.

Finding shelter

Exhausted, I knew it was no longer possible to return south that same day. Still, I had nowhere to stay in Gaza City.

My sister’s house had been destroyed, as had her other home in Rafah. I tried to recall the names of friends, hoping one might offer me a place for the night.

However, all those I remembered had either been killed or displaced south. Eventually, I managed to contact one friend and met him at the hospital where he worked.

As I entered the hospital, I rubbed my eyes at the sight – a scene that reminded me of life before the war: tranquillity, proper lighting, and a ticket window.

I said to him, “If only you could understand what this simple scene does to my heart. We’ve longed to return to normal life, a life we’ve almost forgotten under the pressure of facing genocide.”

My friend took me to an apartment that had been spared from the shelling, where I would spend the night.

In Gaza, describing any building as “spared from the shelling” means it might have suffered the demolition of some walls, the shattering of windows, and the destruction of furniture inside.

Such was the state of the flat where I spent the night. One of its walls had been torn down, and all its windows and furniture were destroyed.

Naturally, there was neither electricity nor water; these networks had been completely destroyed. Despite all this, it was still a luxurious option, considering the dire conditions in Gaza. It sufficed to have a roof, a mattress, and a blanket.

I had my first night’s sleep in Gaza City. I felt a deep sense of comfort knowing that hundreds of thousands had finally managed to return to it – a city Israel had been intent on depopulating throughout the war.

People continue to face significant challenges: food shortages, the collapse of essential services, and the destruction of homes. But there is no harm in taking a moment of joy to recognize that one of Israel’s red lines had been broken.

My sense of comfort was tangled with my exhaustion, and I soon fell into a deep sleep.

At midnight, I was awoken by the incessant hum of a drone – a constant presence in Gaza’s sky. It serves as a reminder that life under occupation is relentlessly disruptive. The sound made me anxious, but eventually, I drifted back to sleep.

In the morning, the sun’s rays penetrated the room and seemed to embrace me. I felt alive and warm – as though the morning light had rekindled a spark of hope within me, breathing life back into my weary and sorrowful soul.

Ahmed Abu Artema is a Palestinian journalist and peace activist. Born in Rafah, in 1984, Abu Artema is a refugee from Al Ramla village.

RELATED: