The Nakba, or Catastrophe, refers to the violent removal of Palestinians from the land that became the state of Israel in 1948. Zionist/Israeli forces accomplished this clearing through the murder and terrorizing of Palestinian villagers: men, women, and children. At least 700,000 were driven from their homes. The violence and destruction was widely documented then and since, but for many years witness accounts were buried or discounted.

One such account is by a Red Cross official named Jacques de Reynier, who visited the Palestinian village of Deir Yassin immediately after a Zionist militia, called the Irgun, murdered its inhabitants. Reynier, who served as head of the Red Cross delegation in Jerusalem, published his memoirs, including this account, in French in 1950.

In gripping detail, he described the horrors of the massacre and how tales of them caused many more Palestinians to flee, then observed with chilling prescience that:

The effects of this massacre are far from over, since this immense crowd of refugees still lives today in makeshift camps, without work, without hope, the Red Cross distributing U.N. aid to them.

It is shocking how relevant this statement remains, three-quarters of a century later. Without knowing the source, a person could easily believe it was a statement from today. The surviving refugees and their descendants in Gaza have remained in exile. Before October 2023, Palestinian refugees had “upgraded” from tents to solid structures—now, though, many are in tents in the dirt once again. Israeli airstrikes have reduced over 60% of Gaza’s homes to rubble.

In honor of the refugees and of Nakba Day, If Americans Knew has produced, for the first time, an English translation of de Reynier’s account.

Below the translation we’re making available, free, the full text of a chapter entitled “Massacres and the Conquest of Palestine” from Alison Weir’s book, Against Our Better Judgment, that gives more context about the Nakba.

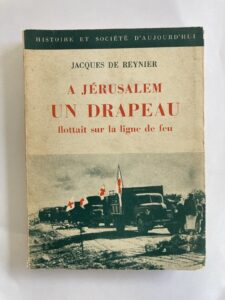

Excerpt from: À Jérusalem un drapeau flottait sur la ligne de feu [In Jerusalem a flag flew on the line of fire]

by Jacques de Reynier, Copyright 1950 by les Editions de la Baconnière à Boudry, Neuchâtel (Suisse)

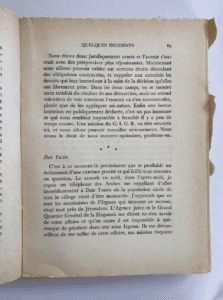

Excerpt: Chapter V – A Few Incidents: P.69

Translated by If Americans Knew (please see translators’ note at end)

Deir Yassin

It’s at precisely that moment that an event of extreme gravity occurred that nearly put everything back into question.

Saturday April 10, in the afternoon, I receive a telephone call from the Arabs begging me to go immediately to Deir Yassin where the civilian population of the whole village has just been massacred. I learn that it’s the extremists of the Irgun who hold this sector, situated quite close to Jerusalem.

The Jewish Agency and the Haganah Headquarters tell me they know nothing of this affair and that, furthermore, it is impossible for anyone to get into an Irgun zone. They advise me against getting involved in this affair, as my mission risks being definitively interrupted if I go there. Not only can they not help me, but they reject all responsibility for what will surely happen to me.

I respond that my intention is to go there, and that the Jewish Agency, by common knowledge, exercises authority over all the territory in Jewish hands, so it remains responsible for my person, as well as for my freedom to act within the framework of my mission.

However, in fact, I don’t know at all how to proceed; without Jewish support, it’s impossible for me to get to this village. And suddenly, upon reflection, I remember that a Jewish nurse from a hospital here had made me take her telephone number, telling me with a strange look that if ever I was in a sticky situation, I could call on her. On the off chance, in the evening, late, I call her and outline the situation. She tells me to be at a designated location at 7 o’clock the following morning and to pick up the person who will be there in my car, then she hangs up.

The next day, at the stated hour and place, an individual in civilian clothes, but with pockets bulging with pistols, jumps into my car and tells me to keep driving without stopping. At my request, he consents to show me the way to Deir Yassin, but he confesses he can’t do much for me.

We go out of Jerusalem, leave the main road and the last post of the regular army, and we take a side road. Very quickly, we are stopped by two soldier-looking types, whose looks are absolutely not reassuring, with machine guns forward and large cutlasses at their belts. I recognize the outfit of those I was seeking. I have to get out of the car and prepare to submit to a methodical search, then I understand that I am a prisoner.

All seems lost, when an immense fellow, at least two meters tall, built like a tank, arrives, jostles his comrades, takes my hand and crushes it in his enormous paws, yelling I don’t know what. He understands neither English nor French, but in German, we manage to understand each other perfectly. He expresses his joy at seeing a delegate of the C.I.C.R. [Red Cross], because, as a prisoner in a camp of Jews in Germany, he owed his life to our interventions three times over.

He declares that I am more than a brother to him, and that he’ll do whatever I ask of him. With such a bodyguard, I felt capable of going to the end of the world and, for a start, we go to Deir Yassin.

Having reached a ridge, 500 meters from the village, which we can see below us, we have to wait a long time for authorization to advance. Arab fire lets loose every time that someone attempts to pass on the road and the commander of the Irgun detachment doesn’t seem disposed to receive me.

Finally he arrives, young, distinguished, perfectly proper, but his eyes have a peculiar shine, cruel and cold. I explain to him my mission, which has nothing in common with that of a judge or an arbitrator. I want to save the wounded and bring back the dead. Besides, the Jews have signed the commitment to respect the Geneva Conventions and my mission thus has an official character.

This last statement provokes the anger of the officer, who asks me to take into account once and for all that here it’s the Irgun that commands and no one else, not even the Jewish Agency, with which they have nothing in common.

My “tank” [referencing the man who was built like a tank], seeing the tone rise, intervenes, and finds the right arguments, because suddenly the officer tells me that I can act as I see fit, but under my own responsibility.

He tells me the story of this village, populated exclusively by Arabs, numbering about 400, unarmed since forever and living on good terms with the Jews who encircle them.

According to him, the Irgun arrived 24 hours ago and gave orders, by loudspeaker, for the whole population to evacuate all the houses and surrender. Time to execute the order, a quarter hour.

Some of these unfortunate people came forward and were apparently made prisoners, then released shortly afterwards towards the Arab lines. The rest, not having executed the order, got what they deserved. But no need to exaggerate, there are but a few dead, who will be buried as soon as the “cleaning” of the village is done. If I find bodies, I can take them, but there are surely no wounded.

This tale sends chills down my spine.

I then return to the road to Jerusalem and go get an ambulance and a truck that I’d alerted via the Red Shield. The two Jewish drivers and doctor aboard them are more dead than alive, but they follow me bravely. Before arriving at the Irgun post, I stop and inspect these two vehicles. Good thing I did, because I discover two Jewish journalists getting ready to do the reporting of their lives! Unfortunately for them, I had to send them packing, and quite energetically.

I arrive with my convoy at the village, the Arab fire ceases. The troop is in field uniform, with helmets. All young people and even adolescents, men and women, armed to the teeth: pistols, machine guns, grenades, but also big cutlasses that they hold in their hands, most still bloody. A young girl, beautiful, but with the eyes of a criminal, shows me hers, still dripping, that she carries around like a trophy. It’s the cleanup crew that certainly carries out its work very conscientiously.

I attempt to enter a house. Ten or so soldiers surround me, machine guns aimed at me, and the officer forbids me to move. Someone will bring the dead if there are any, he says. I fly into one of the worst rages of my life, telling these criminals exactly what I think of their way of doing things, threatening them with every possible wrath, then I push past those who surround me and enter the house.

The first room is dark, all in disorder, but no one is there. In the second, I find among the gutted furniture, the blankets, the debris of all sorts, a few dead bodies, cold. Someone cleaned up here with machine guns, then with grenades; they finished with knives, anyone could tell. Same thing in the next room, but as I leave, I hear something like a sigh.

I search everywhere, move each dead body, and end up finding a small foot that is still warm. It’s a little girl of ten, badly hurt by a grenade, but still alive. As I want to take her away, the officer forbids me and blocks the door. I push past him and pass with my precious cargo, protected by my “tank” [referencing the man who was built like a tank], the courageous one.

The loaded ambulance leaves with orders to get back as soon as possible. Since this troop hasn’t yet dared to attack me directly, I am able to continue. I give orders to load the dead bodies from this house onto the truck, and I enter the neighboring house and so forth. Everywhere it’s the same dreadful spectacle. I find just two people still alive, two women, including an old grandmother, hidden behind some bundles of firewood, where she’d stayed still for at least 24 hours.

There were 400 people in this village, about 50 fled, three are still alive, all the rest were intentionally massacred, deliberately, because, I have noted, this troop is admirably in hand and only acts under orders.

I return to Jerusalem, go the Jewish Agency, where I find the leaders dismayed, but excusing themselves by claiming, which is true, that they have always said they have no power over the Irgun or Stern. But the fact remains, they did nothing to prevent some hundred men from committing this unspeakable crime.

I go to visit the Arabs next. I say nothing of what I’ve seen, but just that, after a first and rapid visit to the location, it seems there are several dead and that I want to know what to do with them, where to take them. The Arabs’ indignation is very understandable, but it stops them from making a decision. They’d like the bodies brought to the Arab side, but fear a revolt among the population, and don’t know where to store them or where to bury them.

Ultimately, they decide to ask me to see to it that they are given a proper burial, in a location that will be recognizable later. I commit to it and leave again for Deir Yassin.

I find the Irgun people in a very bad mood, they attempt to stop me from approaching the village and I understand when I see the quantity and especially the condition of the corpses that have been lined up on the main street. I request firmly that a burial be carried out and demand to be present for it. After discussion, they do indeed begin to dig a large grave in a little garden. It is impossible to verify the identity of the dead, because they don’t have any papers, but I have their descriptions noted very precisely, with approximate ages.

When night comes, I return to Jerusalem, saying I want to come back the next day.

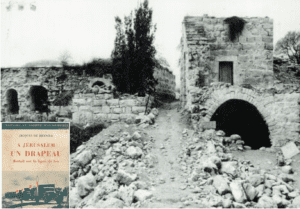

Two days later, the Irgun had disappeared from the area, and it was the Haganah that had taken possession of it. We discovered different places where the dead bodies had been piled up, without decency or respect, out in the open.

Back in my office, after this last visit, I receive two men, in civilian clothes, very well-dressed, who have been waiting for me for more than an hour. It’s the commander of the Irgun detachment and his deputy. They have prepared a text that they ask me to sign. It’s a declaration according to which I have been very courteously received by them, I have obtained all the assistance I desired in the accomplishment of my mission and I thank them for the aid they have given me.

As I show signs of hesitating and even begin to discuss, they tell me that if I value my life, I must sign immediately. So I had no other option left than to persuade them that I didn’t value life at all and that a report completely opposite to theirs was already on its way to Geneva. I add that besides I’m not in the habit of signing unknown texts but exclusively those constituted by myself.

Before letting them leave, I explain our mission to them once again and ask if they will oppose it in the future or not. That day I got no response, but later, in Tel Aviv, I saw them again; they wanted our help for some of their own, and in thanks for our assistance, they helped us greatly on various occasions, handing over to us without question certain hostages that we requested.

This affair of Deir Yassin had immense repercussions. The press and the radio spread the news everywhere, to the Arabs as well as the Jews. Thus, on the Arab side a general terror was created, which the Jews always skillfully managed to keep alive. Both sides made it a political argument and the results were tragic.

Driven by fear, the Arabs left their homes to withdraw to their side. Isolated farms, then the villages and finally the towns were thus evacuated, even when the Jewish invader had only made the gesture of wanting to attack.

Ultimately, some seven hundred thousand Arabs turned into refugees, abandoning everything in great haste, and with the sole aim of avoiding suffering the fate of those in Deir Yassin. The effects of this massacre are far from over, since this immense crowd of refugees still lives today in makeshift camps, without work, without hope, the Red Cross distributing U.N. aid to them.

The Jewish authorities were very annoyed by this affair that took place just four days after they had signed their commitment to respect the Geneva Conventions. They begged me to approach the Arabs to explain to them that it was an unusual accident and that the true authorities would respect their commitment. I responded that I would like to try, but couldn’t hide my displeasure, nor my fears regarding the future.

The Arabs were absolutely furious and appeared totally disheartened. For their part, they no longer expected anything good from the Jewish side and wondered if it wouldn’t be better to abandon all humanitarian ideas concerning them. It was certainly not easy to calm them down, by persuading them that the wrongs of some would in no way excuse those of others.

On the contrary, we said, the fact that the Arabs would keep their promise would prove to the world their honesty and that they were true to their word. We assured them that our long experience prohibited us from doubting them, and that we knew that they would conduct themselves with dignity and humanity, no matter what happened.

After this memorable session, we had the impression that all was not lost, but it had come close.

Our intervention in this affair raised the prestige of our mission. The Jews observed our steadfastness and were astonished to see that we had returned alive from Deir Yassin, without any help from them. They were grateful to us for not having done any publicity or publications, neither to the press nor the radio, and noted our perfect neutrality on this occasion.

Any other approach on our part would only have worsened a conflict that was already cruel enough, and other innocent people would have fallen victim to reprisals.

The Arabs, for their part, understood even better the need for our support and showed much more trust in us from then on.

Translators’ note:

This translation makes every effort to be faithful to the original text. It is an ongoing effort subject to refinement if we find compelling evidence for any slight changes to the English version. Due to the highly sensitive nature of the text, we have generally opted to stick closely to the original French rather than to adjust for more natural sounding phrasing in English.

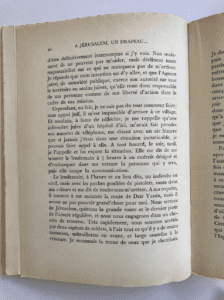

There are some small cases where the author’s words could be interpreted with slightly different meanings (for example, whether the Irgun group at Deir Yassin engaged in some “discussion” or “argument” before beginning to dig a mass grave). However, all the main details of the account are, in our view, crystal clear and not open to any meaningful differences in interpretation. We are providing images of the original 1950 text in French at the end of this post.

We welcome correspondence from anyone who finds any errors in the translation, and we will update this translation in the future if we find any evidence-based improvements to this initial effort.

Excerpt from: Against Our Better Judgment: The hidden history of how the U.S. was used to create Israel

By Alison Weir

[The numbers in brackets represent citations. To view the citations, please purchase the print or Kindle version of the book.]

Chapter 11: Massacres and the Conquest of Palestine

The passing of the partition resolution in November 1947 triggered the violence that State Department and Pentagon analysts had predicted and for which Zionists had been preparing. There were at least 33 massacres of Palestinian villages, half of them before a single Arab army joined the conflict.[232] Zionist forces were better equipped and had more men under arms than their opponents[233] and by the end of Israel’s “War of Independence” over 750,000 Palestinian men, women, and children were ruthlessly expelled.[234] Zionists had succeeded in the first half of their goal: Israel, the self-described Jewish State, had come into existence.[235]

As Israeli historian Tom Segev writes, “Israel was born of terror, war, and revolution, and its creation required a measure of fanaticism and cruelty.”[236]

The massacres were carried out by Zionist forces, including Zionist militias that had engaged in terrorist attacks in the area for years preceding the partition resolution.[237]

Descriptions of the massacres, by both Palestinians and Israelis, are nightmarish. An Israeli eyewitness reported that at the village of al-Dawayima:

“The children they killed by breaking their heads with sticks. There was not a house without dead….One soldier boasted that he had raped a woman and then shot her.”[238]

One Palestinian woman testified that a man shot her nine-month-pregnant sister and then cut her stomach open with a butcher knife.[239]

One of the better-documented massacres occurred in a small, neutral Palestinian village called Deir Yassin in April 1948 – before any Arab armies had joined the war. A Swiss Red Cross representative was one of the first to arrive on the scene, where he found 254 dead, including 145 women, 35 of them pregnant.[240]

Witnesses reported that the attackers lined up families – men, women, grandparents and children, even infants – and shot them.[241]

An eyewitness and future colonel in the Israeli military later wrote of the militia members: “They didn’t know how to fight, but as murderers they were pretty good.”[242]

The Red Cross representative who found the bodies at Deir Yassin arrived in time to see some of the killing in action. He wrote in his diary that Zionist militia members were still entering houses with guns and knives when he arrived. He saw one young Jewish woman carrying a blood-covered dagger and saw another stab an old couple in their doorway. The representative wrote that the scene reminded him of S.S. troops he had seen in Athens.[243]

Richard Catling, British assistant inspector general for the criminal investigation division, reported on “sexual atrocities” committed by Zionist forces. “Many young school girls were raped and later slaughtered,” he reported. “Old women were also molested.”[244]

The Deir Yassin attack was perpetrated by two Zionist militias and coordinated with the main Zionist forces, whose elite unit participated in part of the operation.[245] The heads of the two militias, Menachem Begin and Yitzhak Shamir, later became Prime Ministers of Israel.

Begin, head of the Irgun militia, sent the following message to his troops about their victory at Deir Yassin:

“Accept my congratulations on this splendid act of conquest. Convey my regards to all the commanders and soldiers. We shake your hands. We are all proud of the excellent leadership and the fighting spirit in this great attack. We stand to attention in memory of the slain. We lovingly shake the hands of the wounded. Tell the soldiers: you have made history in Israel with your attack and your conquest. Continue thus until victory. As in Deir Yassin, so everywhere, we will attack and smite the enemy. God, God, Thou has chosen us for conquest.”[246]

Approximately six months later, Begin (who had also publicly taken credit for other terrorist acts, including blowing up the King David Hotel [247] in Jerusalem, killing 91 people) came on a tour of America. The tour’s sponsors included famous playwright Ben Hecht, a fervent Zionist who applauded Irgun violence,[248] and eventually included 11 Senators, 12 governors, 70 Congressmen, 17 Justices, and numerous other public officials.[249]

The State Department, fully aware of his violent activities in Palestine, tried to reject Begin’s visa but was overruled by Truman.[250]

Begin later proudly admitted his terrorism in an interview for American television. When the interviewer asked him, “How does it feel, in the light of all that’s going on, to be the father of terrorism in the Middle East?” Begin proclaimed, “In the Middle East? In all the world!”[251]