Palestinians attempting to enter Shuhada Street held outside checkpoint 59 in Hebron (credit: EAPPI/Sabrina Tucci).

Israel exercises direct control over the 20% of Hebron City, known as H2, which is home to approximately 40,000 Palestinians and a few hundred Israeli settlers. Israeli policies and practices have resulted in the forcible transfer of Palestinians from their homes in Hebron city, reducing a once thriving area to a ‘ghost town’. The living conditions of those Palestinians who remain in the closed and restricted areas have been gradually undermined, including with regard to basic services and sources of livelihood.

from OCHA, oPt, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, occupied Palestinian territories

KEY FACTS

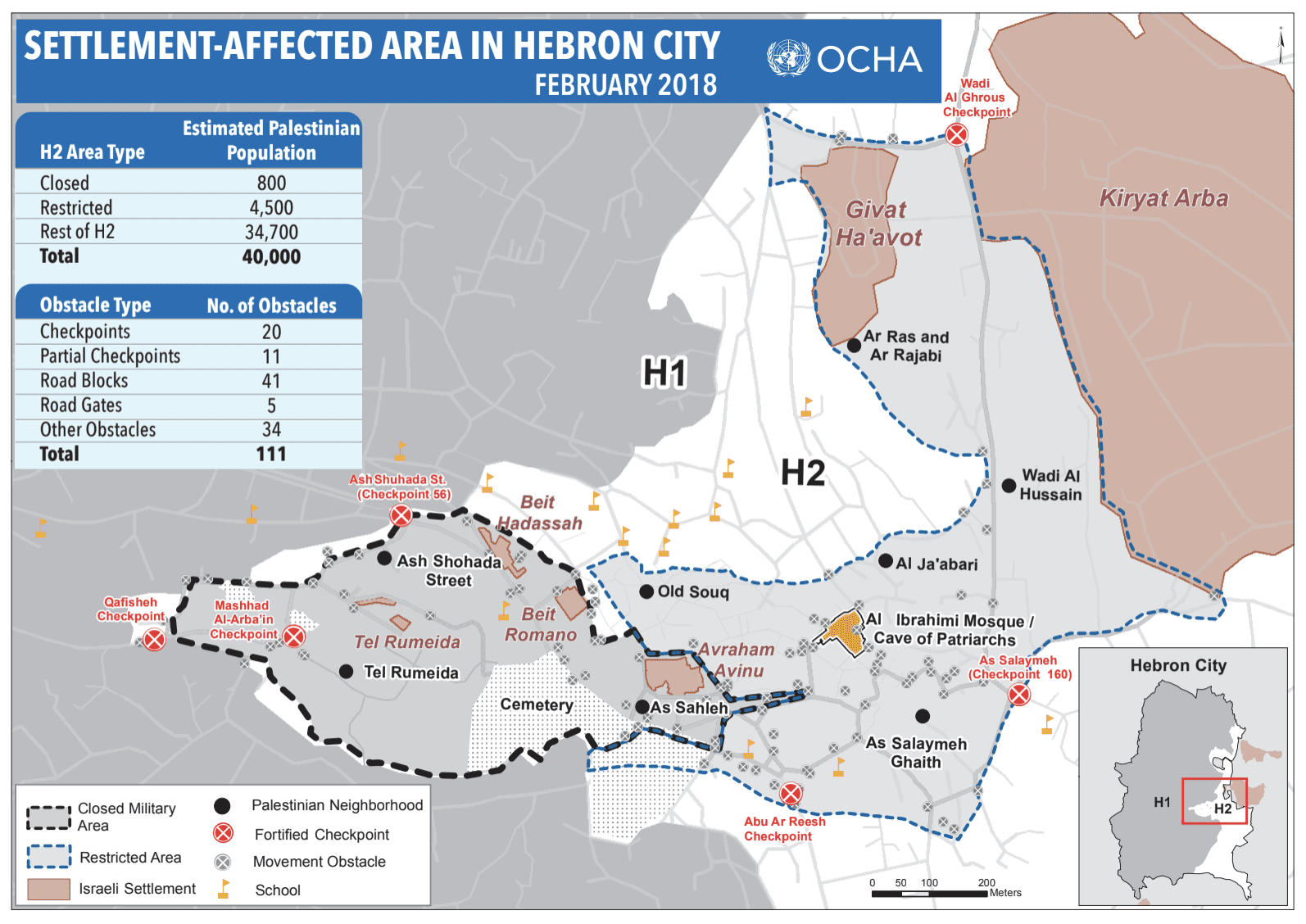

- Israel exercises direct control over the 20% of Hebron City, known as H2, which is home to approximately 40,000 Palestinians and a few hundred Israeli settlers living in five settlement compounds.(1)

- At present, over 100 physical obstacles, including 20 staffed checkpoints, segregate the settlement area and its surroundings from the rest of the city, impacting on the freedom of movement of the entire Palestinian population of H2, as well as on other residents of Hebron city.

- H2 has long been a site of friction between Palestinians and Israeli forces and settlers. A wave of Palestinian attacks against Israelis in H2 since October 2015, which as of February 2018 resulted in one Israeli and 27 Palestinian fatalities (the majority suspected perpetrators), has led to a tightening of restrictions.

- Since late 2015, the settlement area of H2 is declared a closed military zone’, further isolating over 800 Palestinian residents, all of whom must register with the Israeli authorities and be screened at a checkpoint to reach their homes; access is on foot only, and visitors are not allowed.

- Another 4,500 Palestinians reside in streets adjacent to the Israeli settlements, where Palestinian vehicular movement is almost totally prohibited, and pedestrians must be screened at a checkpoint to access the restricted area.

- During the past two years, four checkpoints controlling access to the closed and restricted areas were fortified with towers, turnstiles and metal detectors, and another two similar checkpoints have been added.

- Nearly 260 housing units in the closed and restricted areas, or 40% of the housing stock of these parts of the city, have been abandoned by their Palestinian residents and are empty, according to a 2015 survey.(2)

- 512 Palestinian businesses located in these areas have been closed by military order, and more than 1,000 others have shut down due to restricted access for customers and suppliers.

HUMANITARIAN IMPACT

- Policies and practices implemented by the Israeli authorities, citing security concerns, have resulted in the forcible transfer of Palestinians from their homes in Hebron city, reducing a once thriving area to a ‘ghost town’.(3) These have included severe movement restrictions, including prolonged curfews, closure of businesses, recurrent search and arrest operations, and lack of adequate law enforcement on violent settlers. Some of the abandoned homes have been re-occupied by other Palestinian families.

- The living conditions of those Palestinians who remain in the closed and restricted areas have been gradually undermined, including with regard to basic services and sources of livelihood. To reach their schools, children must take long detours and face harassment by Israeli settlers, and searches at checkpoints; the access of ambulances and municipal workers is hampered due to

coordination requirements by the Israeli authorities; and commercial establishments in the closed and restricted

area have either closed or seen their incomes dwindle since the imposition of access restrictions. - The isolation of the settlement area and its surroundings from the rest of the city has severely disrupted the family and social life of the Palestinians living there and undermined their dignity and psycho-social well-being. In the past two years, only those registered as ‘permanent residents’ have been allowed through the checkpoints, preventing relatives or friends from visiting and reducing marriage opportunities for the younger generation.

- Attacks and intimidation by Israeli settlers have been key components of the coercive environment exerted on Palestinians living in the vicinity of the settlement area. The frequency and severity of this phenomenon has been mitigated in recent years by the decline in Palestinian presence in the area, the protective deployment of humanitarian and human rights staff, and preventive measures by the Israeli authorities. Concerns about lack of accountability, including the closure of cases of settler violence without indictment, remain.

- As the occupying power, Israel must protect Palestinian civilians in Hebron city, ensure that their humanitarian needs are met, and that they are able to exercise their human rights, including their right to freedom of movement and to be free from discrimination. All settlements in the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt) are illegal under international law and Israel must halt and reverse their development.(4)

Footnotes:

1. In 1997, pursuant to an agreement with the PLO, Israel handed control over 80% of the city (H1) to the Palestinian Authority.

2. Hebron Rehabilitation Committee, Hebron’s Old City Preservation and Rehabilitation Master Plan. In the entire area covered by the survey there were 1,076 abandoned housing units.

3. For reference to the occurrence of forcible transfer in H2 see Report by the Secretary General, A/HRC/34/3, para. 28, March 2017.

4. On Israel’s legal obligations see Report by the Secretary General, A/72/564, para. 66, Nov 2017.